Charities: Is it time to quit?

No! Remember what it's all for. Plus: Why charities are like Eurovision. Also: seizing the means of fishy production.

The funny personal bit

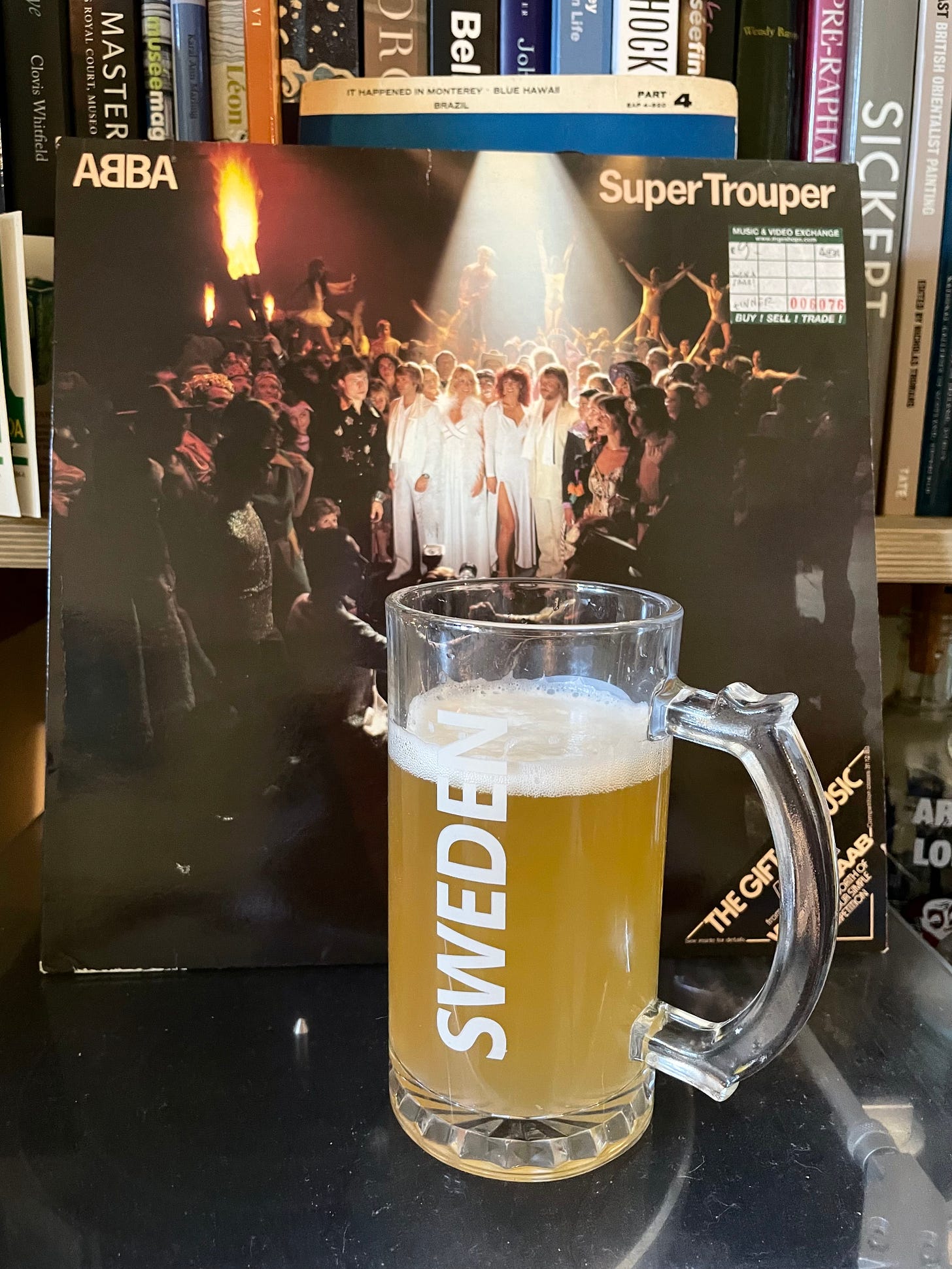

Last Saturday night I had my best Eurovision in a long time. The evening began with a taster of the B-52s (tragedy they’ve never been able to take part), and then the ceremonial playing of Abba’s Super-Trouper album; a personal favourite. My intrepid partner, our librarian friend, and Trevor, who left his important job on Border Patrol in the garden, settled in for the best one in years. Batshit brilliance. I loved Lithuania who did doomcore The Cure in grey tunics. I loved Finland. There was an attractive gentleman from Armenia who appeared to be covered in raw sewage. (It’s tough in Armenia.) And there was a British entry that as usual seemed to be produced or chosen by people who had only read a Guardian article about Eurovision. On Sunday, I had the most Wagnerian hangover, which continued into Monday. All worth it.

This week: a quick recap on how to piss off every trustee in the UK. Then a roundup of the latest craziness in trusts and foundations world - fundraising codes, Lists and the end of infrastructure. Then: why you should stay in charities. And then some more on the very fishy notion of teaching a man to fish, from the world of US international development.

See you in three weeks with the next instalment (I’m away for a week inbetween)…

Latest enemies made

Last week’s essay had an interesting response. It got a smattering of new subscribers and one or two more ‘likes’ than usual. And as ever I had a few people - all of them trustees as well as those who have ‘had’ trustees - saying they were very glad that somebody had dared to raise the issues. And then a couple who acted like I had called their children ugly. (And you know what, I bet their children are ugly.) And a load of diving in with technical tweaks and solutions as a way of pretending there are no problems - pretty much exactly the point of the article.

One objection was that most trustees do not believe that they are protecting the cash of the rich. I’ve no doubt that’s true. But that reminded me again of Owen Jones in ‘The Establishment’, which he says is “an explicit rejection of the idea that the Establishment represents a conscious, organized conspiracy. […] Nor, I should re-emphasize, does the book place the blame on 'bad' individuals with power. It is the system - the Establishment - that is the problem, not the individuals who comprise it.”

The point is, it’s not even necessarily that people think certain things - at least consciously. If you set up the system right, they don’t even need to explicitly think it any more.

Anyway, fortunately, this week we’re mostly back to slagging off philanthropists and trusts and foundations. So you can safely share and feel on the right side of history.

Which we are.

Shitshow a-go-go: what’s shaking down in Charityville?

There’s a tendency at the moment to write off concerns about charities as they relate to trusts and foundations because the size of the ‘pot’ hasn’t changed - that there is still just as much trusts money in the sector. One consultancy newsletter this week said they apprently ‘haven’t heard this discussed’ in what they called ‘gossip and chatter’ in the sector. But it’s a bit of a straw man isn’t it, saying you haven’t ‘heard’ anyone else saying something. Maybe listen harder.

Anyway, some of us have mentioned it a lot. And many other sensible people have noted that the changes are in patterns of giving, not in the size of the pot from foundations. We’ve also noted that almost all of the data we have beyond 360 Giving’s very limited data set about giving sizes, even from ‘reputable’ think tanks, is ‘finger in the air stuff’. Most giving is secretive - this is why 360 Giving was set up.

Meanwhile, within the sector itself, it’s not like there is any shortage of deep data dives: Caroline Danks and Jo are absolutely rolling in complex data. Caroline’s analysis of fundraising ROI is great - detailed and nuanced.

Far from gossip and chatter. Meanwhile Jo’s overview pulled together very significant information on collapsed charities and serial redundancies. Jo called this ‘A very quiet crisis’ - and it’s largely quiet because it’s very helpful for some to keep it so.

As we know, Jo also provides a crowdsourced spreadsheet of incredibly substantial funding changes. She, and a whole range of community-minded fundraisers, are doing what membership bodies and infrastructure organisations can’t be arsed to. As for me, I try to pull together rigorously sourced news and theoretically-informed critique every two weeks (and can’t sleep for a week afterwards wondering if I’ll ever work again). So there’s a lot more than gossip and chatter happening. We’re not just talking anecdotal evidence here are we?

The changes

I think by now everybody knows that there isn’t a big shift in the size of the trusts and foundations ‘pot’, even despite ‘pauses’. For example, Henry Smith gave out more money before it closed than ever before - the pause just represented (an admittedly rather disruptive) ripple. Others have not been anywhere near as practical about it. It’s all about the change in the shapes and patterns.

As for broader changes, I’ve also seen major shifts towards different kinds of ‘cause’. Again, difficult to pin down in data given how limited the data sets are. I’ve noticed significant shifts toward targeting and away from more cross-cutting and intersectional possibilities like, say, advice and poverty reduction. (There is more of this to come.) There is also a tendency now to specify that those crosscutting programmes will only be funded if they are made specialist. Eg. for asylum seekers and migration, women, or racialised communities.

Special programmes targeting the specific needs of particular communities are absolutely vital - but we also need to remember that many of our needs are shared. I sometimes worry that we are just redrawing the lines of the deserving poor, this time on the basis of history and identity. I remain unsure if this is emancipatory or just a way of further dividing people and enacting precisely the kind of scarcity model that those critical of equity and diversity programmes imagine. [It’s hard to say this at the moment without sounding like raving Reform supporter or Trumpist. But that’s how their kind of divisive rhetoric works - their rabid voices drive out the nuance and complexity we need to be able to work together.]

Extreme targeting to single causes (I’m not talking now specifically about targeting ‘people’ here) also means that community centres and organisations who cross divides are going to die, with less support than ever for the glue that binds communities together. Infrastructure is yet another question - more on which later. In terms of sources, one of the biggest issues is with the huge decrease in public sector funding and individual giving, which is pushing more people into the trust and foundations space, plus our increasing costs.

But let’s think about this: telling us all that the pot has stayed the same size, or even that it has grown with inflation is missing the whole point isn’t it. The point, fundamentally, is whose ‘pot’ it is. The point is that this is a minuscule, scabby crusted corner of the overall ‘pot’. The point is the ludicrously unfair distribution of the overall pot - wealth.

The recently updated Sunday Times Rich List (which we have a different name for in my house) tells us all this again. I’ve talked to people this week who are frantically combing it to see who they can tap into, with their trustees badgering them and asking why they can’t get money from some oleaginous Russian oil baron. Many have a sense of both panicky opportunity and a gnawing sense of sickness and disgust in the pit of their stomach.

Time to get out?

And that segues us into the people I know who are either trying to, or considering whether to, get out of the voluntary sector. A lot of us are burned out. These are people who’ve worked in it their whole lives. They just feel like they’ve had enough. Some are younger and haven’t seen a big crisis before. Others have seen a few and are absolutely sick of it. Others, it must be said, have been sacked. There are more and more redundancies happening - thousands.1 Especially those who are more senior, so who have spent more of their career here. Marketing and comms people seem to be badly hit, as do people in ‘glue’ management roles. The question for a lot of these people is how transferable their skills are perceived to be. Given the contempt that the private sector holds charities in, it’s always going to be very tough to get out even if you want to. I used to say I’d go and work in a pub, but there aren’t any left.

Fundraisers especially are feeling this: like I said before, they are at the biting point of wealth and work, and of massive inequality, and the entitlement and power discrepancies in our society.2 Alongside charity CEOs, who are often the key fundraiser in smaller places.3 They plead with the wealthy on behalf of the poor, as they watch inequality go through the roof. As well as simply receiving endless demands from people who have no clue about reality, they’re seeing more and more the massive faultlines and ethical problems. They’re wondering how you can continue working in a system which is broken, unfair and may just be propping up the biggest problems in society.

Stop being polite

Of course they also face a general lack of status (even within the sector where they are seen as a necessary evil), but also from the wider public. But I was very encouraged by the new fundraising code, which I went to a webinar on this week. (I really like the new principles approach rather than rules-based.) Do you know what I most liked? They’ve taken out the requirement for fundraisers to be ‘polite.’ Obviously that doesn’t mean you can just be hostile, or over-insistent, or any of the things they still require - especially if you want to get any cash. What they were clear about was that there was a danger that requiring ‘politeness’ was not allowing fundraisers to retain their dignity when they are met with unreasonable behaviour. That includes the rampant sexual harrassment and bullying they experience, or aggressive behaviour on the street. So, if someone grabs your ass or swears at you, feel free to call the police or swear back.

But I want to push a bit beyond that. Deep down, there must be in all of us a recognition there about what kinds of positions fundraisers can be put in, and an inherent power dynamic. And that is not only a matter of professional power: it is fundamental to the very model of the situation charitable work finds itself in, in our society.

I think we need to think more explicit about the extent to which we are forcing ourselves to be ‘polite’ at a general level when we are dealing societally with outrageous and unjust wealth accumulation. Perhaps it’s time we all stopped being so polite.

So should you just get out?

Is it all too much of a shitshow? Is it so broken it’s no longer worth it?

No! Well, not to me.

Let me explain. As you have seen, I am a MASSIVE Eurovision fan. What I love is the sense of unity and love and joyful silliness and hope for the future. It’s utopian. It’s cosmopolitan, multicultural. It’s all about ideals. Or supposed to be.

Now, it’s also about naked capitalism… but… shut up. And the horrible stuff last year nearly ruined it for me. And they treat artists horribly. And they were sponsored by Morrocanoil, a large Israeli company. (Don’t get me wrong - I fought with every fibre of my being and just about managed not to do a paid vote for Finland - they’re not getting a penny of my cash.)

But stop it! Let me have this! Every year the International Queer Cup Final makes me remember the version of the world I want to see. Love, song, joy, and as much as camp as possible.

Eurovision is just one of the things I get like this about. I went to Disneyland a few years ago (no, I don’t have kids - what does that have to do with it?) and my favourite ride was ‘It’s a small world’. Model UNs and World’s Fairs are my absolute shiz (I went to the one in Milan and blew my rent on souvenirs).4 But I know the faultlines are clear. Patronising Orientalism. Latter day colonialism.

I also love the idea of Disneyland being ‘The Happiest place on Earth.’ But don’t even get me started on Disney. Rampant capitalism. Cultural hegemony. Cynical marketing. Farming children - and middle aged gay men.

But in other ways, my community centres were miniature Eurovisions or Disneylands. When you step over the threshold, I want you to feel totally welcome, comfortable, loved and like you belong. When I walk into one now, the hairs stand up on the back of my neck and I feel physically revived. And when I was bid-writing for a charity doing dance workshops for children with disabilities recently, I found myself giggling and beaming with joy watching the videos. And I still remember the chaotic madness of a Halloween party where we discovered what happens when you provide large amounts of sugar to children and adults alike. And the Christmas party where Santa stole the minibus in a disagreement about billing and, to avoid disappointing 200 children, a very talented community organiser had to invent Pinguina the Christmas penguin. Because we happened to have a penguin costume. Don’t ask.

What Eurovision and Disneyland remind me of is my human ability to be extremely cynical and pessimistic, and extremely idealistic and hopeful all at once. I don’t think this is cognitive dissonance if you own it, accept it, and just integrate it. That’s what pragmatism is.

And no matter what, the charity and ‘nonprofit’ sector is still the vision of society that I believe in. I want people’s needs to be met. And I want to go far, far beyond that. Love, care, support, and flourishing, for people and the planet, freely given. Not scarcity - not even just sufficiency. A world of plenty, I want that. I will continue to fight to make that a reality as well as a principle.5

So, don’t go. Like you, I’m tired. But remember: Pinguina saved Christmas. And we’re trying to create the happiest place on Earth.

Infrastructure meltdown

Basildon, Billericay and Wickford CVS is “set to close due to changes to commissioning and funding structures that have caused an unsustainable financial strain.” We’ve seen more and more infrastructure bodies closing - especially the local and regional ones, which are of such massive value. Local authorities won’t/ can’t pay for them any more. And funders are pulling the plug. The Charity Commission demands compliance and professionalism, but is in no position to provide the support organisations need to provide it - or thrive. These organisations play a significant role in ensuring that charities function. The national infrastructure organisations are just trade bodies.

As Fair Collective put it,

“Once again, it’s small charities that will be hit hardest. The ones already stretched thin. The ones without back-office teams or big reserves. The ones who rely on local infrastructure for: funding advice, training and capacity building, networking and collaboration, a collective voice in local decision-making. We talk about resilience in the charity sector but there is no resilience without infrastructure.”

There’s another problem here. Increasingly, trusts and foundations are taking on this role themselves. Often I hear them talking about how they can start doing the very things infrastructure bodies are meant to do. They want to be ‘more’ than just grant givers. But that then means they are no longer giving grants to the existing infrastructure, and using the money for, honestly, making their own jobs more interesting. I’ve literally been in meetings where they have listed all the things that they could do to help charities, and when somebody in there suggested that they might want to help the amazing infrastructure bodies already doing it, first, they were stunned to discover anyone was, and second, they changed the subject so fast that you could hear a sonic boom.

The thing is, that then gives them additional power, which, given their extremely antidemocratic nature, is a serious problem. As Emma Collier put it: “And they're still the gatekeepers - organisations only get their support if they've already been successful with an application. Not much help for all those organisations struggling to get fit enough for the funding in the first place!”

It’s hard to know what the solution is to local infrastructure unless we fund local authorities to do it again. but even at a national level, some type of infrastructure beyond simply trade bodies is much needed. Things like ACEVO and NCVO are hugely depleted. [Again: my take is that you should disband NESTA and take its endowment and put that into a permanent endowed infrastructure body for the VCS - finally something tangible and socially valuable for all that cash. Another option: tax charitable foundations a certain rate wherever they give anywhere below a certain percentage of their assets per annum (as they do in the US). Use that money to add funds. Roll all of this in with the Charity Commission to provide a support-and-challenge body.]

Without infrastructure, our alignment and collaboration, as a million people who want to change the world, is all the more difficult. Of course, that may be quite useful for some.

Myths and facile fishy (un)charitable adages

I don’t listen to podcasts much - I can’t stand people waffling. If they start bantering, to me it’s just like sitting next to people in a cafe who think their conversation is so witty and incisive that everybody will want to hear it. No, the reason I’m looking at you is because I’m fantasising about you choking on your chai latte. But the Atlantic has some decent ones, as does the New York Times.

As subscribers will know, I have a particular loathing for the old adage about 'teaching a man to fish'. Because it always comes down to avoiding the real question: 'Why have YOU got all the fish? Why do YOU own the river? Why can’t I have some of yours?’

So I was pleased to discover someone else snapping the rod in half on this one in The Atlantic (US current affairs magazine) podcast recently, where Paul Niehaus, an economist and co-founder of the NGO GiveDirectly talked about the idea of the 'poverty trap' and other notions of philanthropic giving. Niehaus is talking, among other things, about direct payments - the idea that the best way to help people who are poor is, (who knew?), to give them some money. There's very substantial evidence in international development now that this often works better than programmes which 'provide interventions' or tell people what to do with the money. (No prizes for guessing why the latter might be attractive to rich philanthropists...)

But he tackled the TAMTF ideology head on. First, he syas that he did some digging and discovered that the original phrase comes from Victorian novelist Anne Thackeray Ritchie. She is actually critical of the idea and suggests that the only reason we don’t give somnebody fish - or money - is because it would “upend the social order.” As he puts it, “today, the way we interpret is 'Don’t just give people money, because they’re not going to use it in ways that have a lasting benefit.' Which I think is just empirically untrue. […] So the origins of the term are actually a critique of inequality [...] But somehow, over time, it’s completely changed, and now the interpretation is: You can’t trust people to make financial choices for themselves. But that’s not what it originally meant.”

As he points out, who are we to decide that teaching is what they need. Maybe they need a fishing rod, or the lake is overfished and we need fewer people to fish to avoid overextraction of natural resources, or maybe we’re just not very good at teaching people how to fish.

And even beyond that, there's still a danger that our critique can be capitalist at root: that, after all is the danger of ‘development’ in its economic form. It leaves the system of inequity and exploitation intact. I want to ask, what if they don't own the river? What if they live in a desert? What if they can't hold a rod? And so it goes. The one thing nobody ever wants to discuss is whether we might be better off fishing together and then sharing the fish more equitably. Or making sure we set aside a portion of our fish for people who can’t fish. That’s not unreasonable, right? Can’t people with more fish can afford to give a few more?

There’s a general tendency for us all to talk about ‘growing the (fish) pie’ rather than changing how the pie is distributed. There is no shortage in the world of (fish) pie. The problem is that some people are just greedy fish-hoarding bastards. Until we look at the fishing analogy from the perspective of ownership and distribution of the resources themselves, we’re just perpetuating the problem.

Teach a man to seize the means of production and then everybody gets some fish.

Another one: ‘What gets measured gets managed’

I have a particular fascination for this type of weird cultural artefact, where a phrase or idea that was once deeply critical gets repurposed over time to argue for the very thing it was critical of. It’s pretty much a case-in-point of how ideology works to incorporate what opposes it. Another one is 'what measured gets managed.' That originally referred to the problem with measuring everything - not a problem with not measuring everything.

Niehaus also talked about a tendency in international development to ‘follow the money’ and to focus on counting things that are easy to count. Of course, because of international development being about, well, money, there is a tendency to be reductive about what it’s trying to achieve.

What we tend to find is that we take an economic model which is based on the idea of constant growth and ‘investment’, where returns are only considered to be effective if ‘line go up’ with a dollar. Sign. Of course, what exactly you;’re measuring says a great deal about your own ideology, values, and goals - and may not necessarily be much about those of the people you’re trying to help. A focus on simplistic metrics - they give the example of increased family income, or other specific economic measures - can be the opposite of rigorous, because it isn’t really about whether you’re helping people, it’s just about your value system and your need to count something. Often people’s lives are not metrics. People’s lives are mostly open questions - especially when it comes to their quality of life (the clue is in the word ‘qualitative’).

Niehaus said discussions about findings from a programme with OXFAM had

“provoked deep thought about: What is the point of global development? […] They found, for example, in one of these programs that a lot of people [in] a program in Vietnam [had used direct] transfers [i.e. donations of cash directly to individuals] to purchase coffins because for them, culturally, religiously, it was very important to be buried in a coffin and not in an open grave. And that’s not something that I think anybody ever measures in our surveys, right? But what if that’s very important to you? Am I okay with that?”

He also mentions the tendency to meausre economic growt without consdeirng what that is meant to acheive - he gives the example of a man who used his direct payment to move back from his city to live with his rural family again. His income reduced. But He spent his life with the family he loved. Wasn’t that a success?

“Again, that’s going to look like an income reduction in the data that we typically collect. It’s because we aren’t great at measuring things like the quality of your relationships with your kids, which are what I think actually matters in life. So I just think that it’s super, super important to take all of the measurements, the outcome stuff, with a grain of salt and with that humility, and sort of trying to remember that people’s own views on what they want out of their lives are very important if we really take that Senian perspective.”

A reminder again: metrics alone will not tell your story - and worst of all, they may just replicate, or even dilute or deform your values and your mission. Unless your mission truly makes money as an end in itself. And what’s the word for that system of values again?

Let’s all flatter the rich again.

Last week, the ACF reposted this article from the Torygraph.

When philanthropy is being set against, and the Telegraph are demonising ‘the Left’, as the article does, you get some idea of what is really going on. (I’m a bit surprised ACF were quite so comfortable with that.) Caricaturing the arguments of ‘the left’ is a rather tired, although sadly effective, tactic.

Most of us on the philanthropic ‘left’ don’t suggest that all philanthropy is a nefarious plot. We do think it’s structurally unfair to ssay the least. But some people are giving this way because they think it’s the right thing. Family trusts do good stuff: Garfield Weston are frankly the unicorn of the sector who have propped up most of the community fabric of the VCS while other more democratic grantmakers have sequestered themselves for a leisurely rethink for a year at a time. Many of us know we have to deal with philanthropy with compromise, pragmatism and a sense of strategic and tactical engagement. For example, George Soros’s money is pretty important in the field of standing up against dictators. We need it more than ever. Even if I don’t think he should have that much money, or that any oligarch should be allowed to influence politics that much.

But even on a practical level, The Telegraph’s argument is typically disingenuous - ignoring the way the tax and influence trade-off really works. ‘Charitable’ causes can mean a lot of things. Philanthropists buy influence, status, and choice on how their ‘taxes’ (which they avoid in this way) are spent: based on their own ideological preferences. For example, some, Like Bryan Souter, one of the signatories of the Centre for Social Justice’s recent ‘Supercharging Philanthopy’ polemic of bad faith self-congratulation and anti-tax propoganda, can spend a fortune on trying to worsen LGBT people’s lives. Others can spend a fortune on ‘charitable’ think tanks that lobby government for their own interests. They can pay for ‘research’ which then provides benefits for their private interests. Or they can plant some trees with schoolchildren to change minds about their rampant pillaging of the environment. There is a vast amount of literature on this which I assume people are more than aware of.

For me, articles like this make it clear that the interests of charity and ‘philanthropy’ are in tension, if not outright conflict. Because they spring from fundamentally different visions of the world, and these are based, I’m afraid, on class. Class, remember, is not just whether you’re called Orlando or Bill (and mea culpa, I think I have inadvertently prolonged this misunderstanding through my more comedic and facetious musings), or how much money you had growing up. It’s about shared social and economic interests. And the class interests apparent in charity are very different from those that rule philanthropy. How could it be otherwise?

That fully explains why we have have ended up with completely separate infrastructure bodies representing the interests of funders, and those representing the interests of charities - they are fundamentally different. Even if the latter always tug the forelock to ‘philanthropy’ because they too need their cash and their approval.

More and more, it seems to me that the interests of charity and ‘philanthropy’ are in tension, if not outright conflict. People who claim otherwise are just doing the ideological work of concealing class relations. (That was my most Marxist sentence yet - next, you’ll find me on the market selling Socialist Worker of a Saturday morning, and pretending to still have a strong Northern accent. )

And finally: many of you won’t be able to read the Torygraph article because yet more of the discourse around philanthropy is taking place behind a paywall. All major philanthropic discussions at present take place behind closed doors - either in special conferences and groupings run by organisations like the ACF, from which charities are excluded, or in trade or elite press which no small charities or individuals can afford to subscribe to. Funders and infrastructure bodies are pandering to this. Journalism needs to be paid for - but this is also a matter of equity. If there’s an interview, it’s in the ridiculously unaffordable Third Sector. If there’s a conference, it’s funder only. This is an elite club. Even information is too expensive for the rest of us.

And finally…

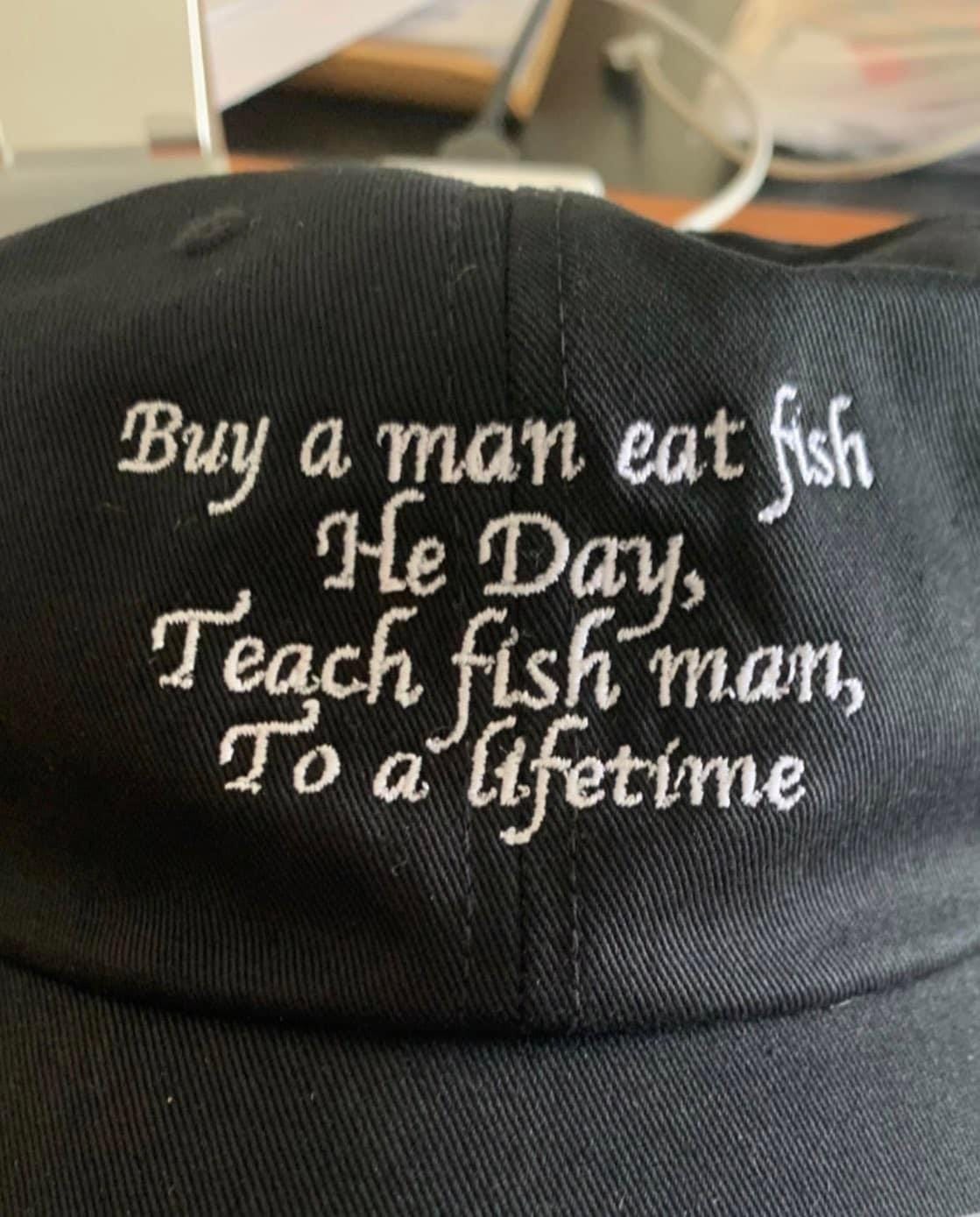

Here is my new badge. This my MY kind of EDI.

Barely Civil Society is trying to create deeper debate in the UK charity sector.

Here are three ways to help BCS make charity braver.

1. Subscribe

Barely Civil Society is a reader-supported publication. Please think about buying a coffee or even getting a paid subscription. It’s about a quid a week, for as many words as you get with most magazines. Or just send this on to your friends or mortal enemies.

2. Share

Linkedin recently changed its algorithm and is no longer showing posts for many VCS writers to a wide audience. (Unless you pay for advertising…) So….

OR….

3.

See Jo’s summary - sadly already out of date with many more new entrants.

See here on fundraiser mental health and burnout. https://www.civilsociety.co.uk/news/charities-must-do-more-to-support-fundraisers-facing-burnout-report-warns.html

See Fair Collective’s wwork on charity CEOs and mental ill health. https://www.faircollective.co.uk/post/small-charity-leaders-mental-health-is-at-crisis-point

It was really shit though - truly just a trade fair.

I also happen to think this is not achievable within the bounds of market capitalism. That is one place I deviate quite fundamentally from Disneyland, Eurovision, and indeed, most charitable funders.