Fundraisers are dangerous

A manifesto for all you greedy little revolutionaries. Plus: Blue Labour is back. And, how can we understand US political alliances?

Welcome to this biweekly edition of Barely Civil Society. Got to say I’m still not feeling very funny, and guess what: the developing political situation is even more stressful if you stupidly decide to regularly write about it…

But anyway, I’ve squeezed out some gags alongside the hand-wringing, and this week the main event is a fundraisers’ manifesto. Why are we seen as so threaterning? Well, actually - because we ARE.

Excitingly, for a lucky bunch of paid subscribers (woohoo! - okay it’s like 3), there is also a look at the worrying turn to the right of Labour and the supposedly communitarian Blue Labour, and a quick look at a good recent analysis of exactly how fascists are creating an alliance in the US Government. Plus some extremely amusing memes.

So if you want extra fascism, UK politics, and memes, can you spring for about £1.25 a week? Go on.

Fundraisers are dangerous

I was struck by a headline in Civil Society a couple of weeks ago.

‘UK’s wealthiest 1% donate £8bn a year, researchers estimate. (Civil Society, 17 Feb 2025 News Chongyang Zhan’)

Now, how you choose your headlines is very important.1 Does this sound impressive?

What about if I then tell you, as the article does later, that this was actually equivalent to “0.4% of their combined £2tn of investable assets in 2023."

Another question: how much tax did that allow them to avoid? How much did this act of generosity cost our society and our public economy?

Why go on about fundraising?

No matter what I write about charities, I always come back to fundraising. I’ve often wondered why. I’m not primarily a fundraiser, although sometimes it’s rolled in with what I do - and as a charity CEO, it was pretty much my whole job. But it’s not my ‘calling’. So why do I keep writing about it?

I think it’s because to me, fundraising sits right at the crux of power, wealth, and inequality in what we do. Nowhere is the fundamental power imbalance that we work in – which is largely economic – more apparent. Let’s face it, they work at the sharp end of inequality: the economics.

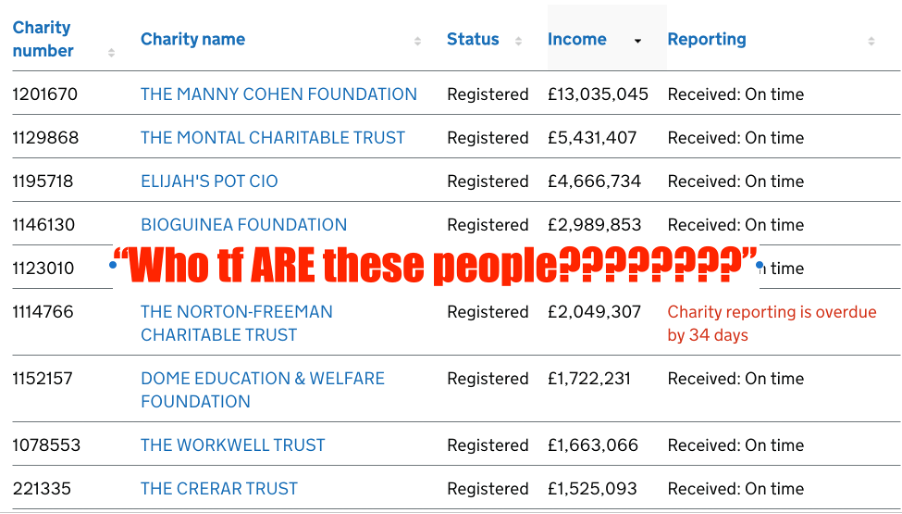

The other day I was taking someone through the Charity Commission’s website. I was showing them some of the weird and wonderful trusts and foundations out there (Jo, this one’s for you). As I took them through, a look of increasingly morbid fascination, and then growing horror, appeared on my colleagues’ faces. I’m so used to this, I have become inured to it, but my friend, shaking his head, just asked “Who TF are these people?”2

And he’s right: there is this weird, slightly creepy subterranean world of cash just hanging around, to be spent how any of these people see fit, and largely just because somebody didn’t want to pay tax. For all of us sitting together, a sort of ‘naked lunch’ moment of realisation set in. We all agreed. This is weird isn’t it.3

The thing is, people who have to fundraise from the wealthy operate at exactly the biting point of injustice and inequality: the economics. Think about that liminal position fundraisers take: they are positioned between the powerful and wealthy, and the needs of the people whose resources those potential donors stole.

They spend all day looking at the vast wealth of trusts, or individuals who sit on their cash and disdain ‘begging letters’

Or vast unaccountable trusts who reassure themselves that they are sufficiently enlightened that they can act as philosopher kings outside of democracy.

They see drawbridges pulled up as funders close their programmes to ‘think’ (there’s that ‘philosopher’ part, folks).

They see gatekeepers, and vast intergenerational wealth.

They see nasty small-minded families and business people hoarding their wealth behind their own often pretty unpleasant ideologies of the ‘deserving poor’, or worse.

Is it any wonder fundraisers are miserable? And are getting a bit punchy?

Why do we distrust fundraising?

My point today is this: fundraising is perhaps the most threatening work that we do, because it is the part of our work that focuses on economic redistribution. No wonder, then, that it is the least popular activity that charities undertake. And further, I want to argue that fundraising goes to the heart of charity - it is not some unfortunate bolt-on we have to endure in order to do the ‘real work’ as we tend to pretend.

First, let me be clear up front. I am not writing today about individual giving. I am writing about the kind of ‘philanthropy’ done by ‘philanthropists’: that is, the wealthy from the captains of industry, to intergenerational and aristocratic wealth, to corporate foundations. And indeed, to an extent, independent trusts and foundations - the biggest and oldest may not directly own their cash, but, boy, do they act like it.

The thing is, fundraising from the wealthy reveals power. Every time a wealthy person opens their wallet and gives something to others, by choice, they risk revealing just how much they have. And that can lead to the very risky question: why do you have it? Where did it come from? All too often, the answer is that it has been extracted - from the very people they now don’t want to give it back to. This is money which is ‘twice-stolen’ - usually with profits extracted from workers - or worse - and then through avoided taxes.4

This is very risky indeed for people who are rich precisely because they are generally pretty good at not giving out money. If you were walking down a street of desperate people who are hungry, you wouldn’t want to open up your Fortnum and Mason’s hamper and give them an oyster. People might wonder why you’re nibbling caviar and they’re chomping on a rat. The fact that philanthropists are always so sure that they don’t want to use their cash to ‘give a man a fish’ rather than teaching him to fish, as the old saw goes, is because people might ask why they’ve got all the f*cking fish. They also risk revealing that aspect of choice that I find so problematic. Who are you to choose?

When wealthy people give money, especially bigger amounts, they’re showing that they can afford to give. And that when they don’t, by extension, they’re choosing not to.

Why are fundraisers demonised?

Because of this, fundraising and charity work has to be ‘disciplined’ in our society. We do this in many different ways, but perhaps the two most pressing are structural, legal and bureaucratic controls – such as legislative and legal frameworks and regulators and the official narratives they use - and wider cultural myths and ‘stories’ we tell every day about fundraising and charity.

That structural control means we are extremely heavily regulated, and much more so than many other industries. We see the endless pages of rules to follow with the Charity Commission. We see the screeds about governance as if it were an end in itself across the sector – an almost hysterical obsession if you ask me. We see fundraisers and charities singled out for regulatory oversight beyond all others – builders have no statutory regulatory oversight, but people who run a charity raffle for old people’s knitting groups have at least two bodies overseeing them. Those regulators will publish at least one story every few months in the press in order to demonise the charity sector to ‘enhance public trust’. We’re told that this is to protect ‘the public’ but I have my suspicions – the majority of regulation in this sphere seems most of all to be designed to protect the money of the wealthy.

Then there are the cultural myths that drive a wider public imaginary, in the press and our day-to-day stories to justify - or delegitimise - our behaviours. We are told that fundraisers are not to be trusted - from the ‘chuggers’ on the street (who even p*ssp me off, I have to admit) to the pool houses and lavish trips the press love to cover.

(Now, I have been known to pilot a pedalo around Peckham park of a lunchtime, with a cocktail in one hand, and a wad of money down the front of my bikini. Well, okay, a can of Tennants Special Brew and a Tesco voucher stuffed in my Primark undies. All on the dime of poor vulnerable trusts and foundations. So I accept that I am part of the problem.)

But that is just the kind of luxury that charities tend to go for, right? These charities go beyond the ‘need’ into the nice to have. In the wider cultural narrative, fundraiser charities are often presented as the organisational equivalent of the benefits cheats in council houses with big TVs. Greedy. Insolent. In search of a free lunch at everyone else’s expense.

This would be bad enough, but what about all those myths we tell ourselves in the sector, as if we needed to keep ourselves on the straight and narrow? How many times have you been warned not to become one of those terrible charities who ‘just chase the funds’? Believed that charities ‘ask for too much?’ Or been told that there are ‘too many charities’ demanding support, taking up precious thinking time, by all those philosopher kings in the trusts and foundations?

Indeed, have you asked fundraisers to work on commission, because their work is worth less than, not just your saintly face-to-face delivery workers, but also your senior managers and admin staff? What are they, bloody Avon?

Or have you ever felt you need to be ashamed of the fact that you pay for fundraising? I bet your trustees have - and maybe asked if a volunteer can do it.5

The Charity Commission even reports on how much we spend on fundraising as a marker of shame - and indeed, shame is one of the key strategies we use to keep charities and fundraisers under control.

Controlling the beggars

Isn’t it interesting how, buried within these disciplinary myths, so many of the admonitions are just not to ask for too much? There is a strange tendency for the powerful and the wealthy to create little mythologies and demonologies of ‘bad people’ who dare to upset their power. But I would ask you: who benefits when charities ask for less?

You might say that this disciplining of fundraising work is simply to avoid ‘nuisance’ or fraud.6 Believe me, this makes sense – and indeed, the actual legal regulation is, I think, the least of our worries. (I’d actually like to see closer regulation of individual fundraising). But I think the mythologising and narratives are far more damaging and more pervasive, and more effective at ensuring the more politically ‘dangerous’ aspects of fundraising are contained: that is, its potential to reveal that there is far too much money in the hands of a few people. And that those people can actually choose to give it away – or not. Next to that is always an even more frightening risk – that people might then ask why this giving is optional, and why, perhaps, that wealth shouldn’t be taken through redistributive and progressive taxation.

Sidebar: The only time philanthropists like giving

But philanthropists do give money! And shout about it! Of course they do - if it allows them to amass further prestige and social power. And most of all, if it can avoid the much worse option. Basically, philanthropists like to keep money close until the real danger – taxation – rears its ugly head.

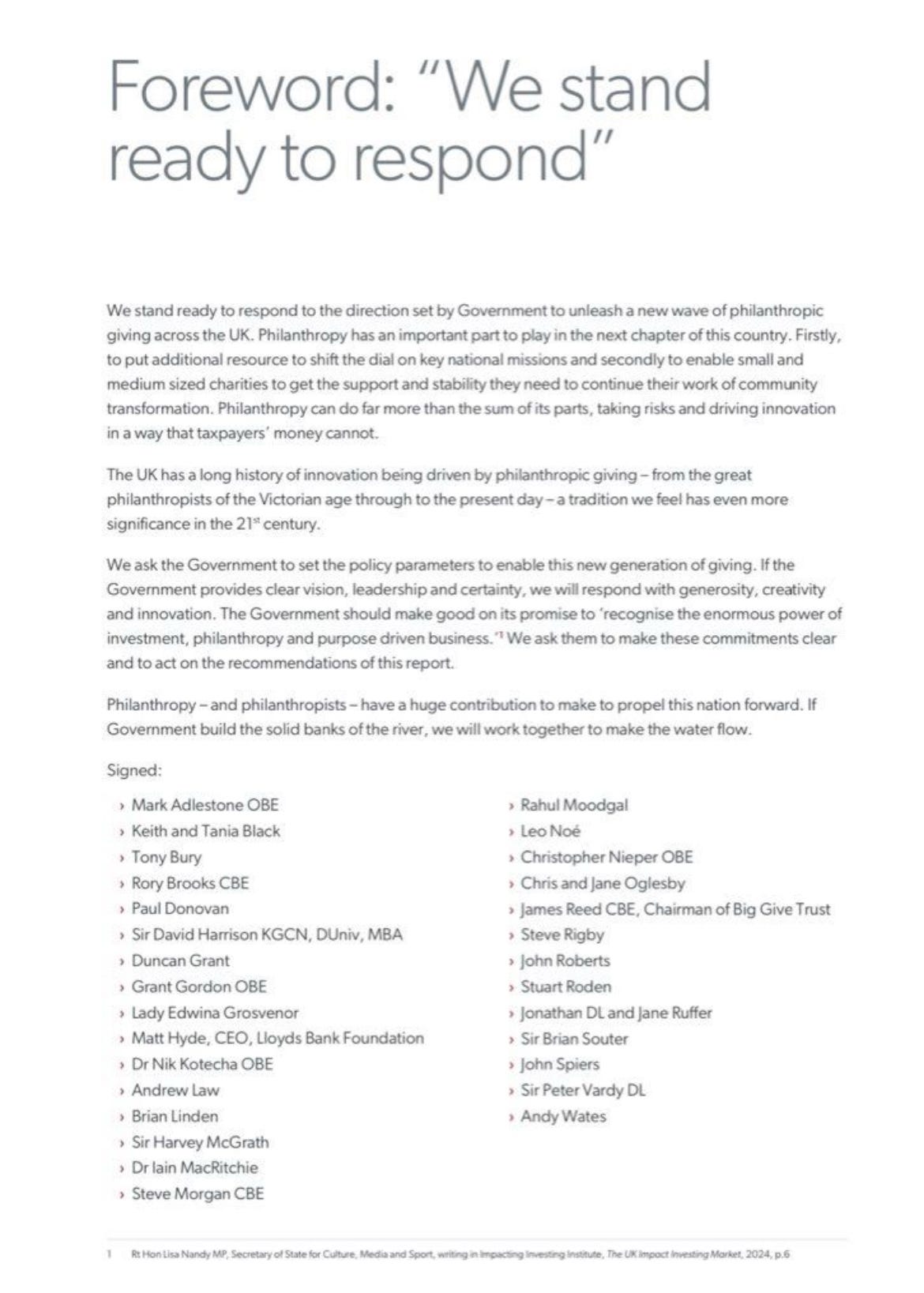

At the stage when taxation is a possibility, you will find that suddenly philanthropist wallets spring open to show how much they can be relied on to be a good sport at the Rotary Club. Iain Duncan’ Donuts’ think-tank for Centre for Social Justice (Orwellian doublespeak name, a lot like ‘Ministry of Truth’, I feel) recently published a report on ‘Supercharging Philanthropy’.

You lucky people: this is where “30 of the UK’s top philanthropists” – including vicious homophobe Brian Souter – tell us they “stand ready to respond” to the challenges faced by the UK and to “propel the nation forward”. Indeed, it tells us that “Philanthropy can do far more than the sum of its parts, taking risks and driving innovation in a way that taxpayers’ money cannot.” [My emphasis.]

Whomp! There it is! You’re not subtle, guys, are you? So you’re saying that you prefer choosing for yourselves what you pay rather than taxation? What an unexpected position.

Oh, and wait, you stand ready to respond with “generosity, creativity and innovation”. Thank God for the creativity and innovation of, for example, the Herculean owner of a few poxy health centres, or of a third-rate bus company. Who else but such great thinkers and social leaders would we ask to take on such a monumental task, after all? You’re so ‘generous’.

So when we say people should follow the money, not the mission, I say: how very convenient for those with the money. It must be very comforting for them. It’s almost as if every strand of social narrative is straining to avoid economic redistribution being considered a reasonable part of charities’ mission….

In a society with grotesque levels of socioeconomic inequality, make no mistake, part of our mission IS the money. Any argument for redistribution is just about the most nakedly political thing we can do in our society. Short of fair progressive taxation, an economy that invests in and values human lives over profit, or an economy that rewards work and care over wealth, fundraising is the only redistributive game in town.

Anyone who tells you otherwise is just ‘fundraising’ for the ‘other side’ – that is, keeping more money in the pockets of the wealthy elites who just don’t want to help any more than they have to.

Is fundraising enough?

So is fundraising a radical act? Will it change the world? Absolutely not. A piecemeal, voluntaristic approach to creating a more just, economically equitable society is a sticking plaster at best, and often a distraction. The fact that so many philanthropists provide such a paltry sticking plaster (or ‘teach you to fish’) only makes it worse. Voluntary giving will never replace a fair tax system with properly funded social security of the sort you tend to find in, not coincidentally, places with a much lesser tradition of organised philanthropy and charity. (Basically, most of Western Europe…)

I’m particularly concerned by the philanthropy cheerleaders in our sector who constantly praise tax-avoiders and profiteers for their kindness, ‘creativity’ ‘generosity’, and indeed, often for their magnificent foresight. When I saw all the people launching in to thank the noble philanthropists in the CSJ’s Linkedin post, I felt a little bit of sick come up. Those kind of fundraisers are dangerous for another reason, I think: they are helping to reinforce a narrative which is regressive and undermining of demands for real economic justice.

So it's not good enough for us to ‘beg’ better. Fundraisers could be even more dangerous in the right way if they refused to play the role they get assigned - if they reject the performance of gratitude, when they expose just how much wealth sits idle.

Until we have a proper political and economic system that makes redistribution a matter of course, fundraising can be a form of resistance - or at least, a small remedy - as long as it also avowedly resists buying into the grotesque self-mythologisation of the rich and the nobility of philanthropy.

I want to see more disruptive fundraising which uses what Liam Neeson once called ‘a very special set of skills’ to make things much less comfortable.

What do I mean by that? Well, after all, fundraisers know where the money is, the bodies are buried, and indeed, they are skilled orators, persuaders, and makers of arguments. Some might say, they are born activists. Those are exactly the kind of skills we need in our political sphere. Perhaps it’s time to put those skills to uses that will change things more fundamentally.

Most fundraisers won’t be able to do this in their day job - although if more charities grow a pair, they might: Oxfam are now campaigning on taxation. Shelter are not afraid to call out the deep exploitation of landowners.

But hey, if your day job has to be flattering the wealthy, at least you could spend your weekends making their lives more difficult. A new generation of fundraisers in the day and activists at night could truly change the world.

Finally: don’t let people tell you you’re somehow a distraction from the mission. Until we get some real political change, you’re the only show in town when it comes to the mission that matters most. Getting some of that money back.

Stay dangerous, comrades.

BUT WAIT! THERE’S MORE!

Starting this week, there’s even more good stuff, and I’m offering everyone the chance to read some more ranting, raving, and misbehaving below.

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to read more on… Blue Labour and the rising threat of Labour’s right wing turn, the weird politics and associations of the US’s facist Government, and some banging memes that you would be a fool to miss... (Including Vladimir Zelensky’s balls, legal advice for activists, and loads and loads of Elon Musk….)…

Blue Labour really scares me

Have you ever heard of Blue Labour? It’s having a resurgence, it is said. The last time was when Ed Miliband took over the party. But it always re-emerges when the Labour party has a crisis of confidence of a particular sort. That is, when feels threatened by the right, and suspects that the best way to win over the working class people is to steal the moves of the nasty party and call it socialism.

At that stage, Maurice Glasman, (now a Trump supporter, and JD Vance’s pal) reappears to tell everyone that the reason left wing parties are failing is because they are too socially ‘progressive’. Blue Labour suggests we should ditch ‘social’ justice and multiculturalism in order to make the argument for economic justice easier to sell. What it likes to focus on is, on the surface, all the stuff I feel like I ought to care about given my VCS background: communities, local power, the value of small, etc. But you see, that can go very wrong. There is a kind of small-minded politics they idealise that is often nativist, anti-progressive, exclusive and intolerant, and far more concerned with levelling than flourishing. They actively court faith groups - all good, depending on which, and what kind, and why…

The problem is, in many ways, what Blue Labour is offering is Trumpism and Farageism with potentially more progressive taxation.

But where is that argument on the economy? The problem again is that Blue Labour’s solution to working class voters choosing the right is to mirror their focus on culture wars. These guys claim to be centre left on the economy - whereas, absolutely right, ‘real’ Labour is centre right (come on, let’s be honest). But the push on migrants, on the family, on ‘local’ communities here is more often dog-whistle politics for Reform voters - and worse.

The Blue Labour moniker is designed to evoke small C conservatism, perhaps of a time before the Tory party became something quite different during the Thatcher era - the amoral scorched earth economic radicalism of the last 40 years that has savaged our society (led by big C ‘Conservatives’). But the problem with Blue Labour’s pitch is that it always leads with the kind of social conservatism, intolerance and xenophobia they - perhaps rightly - perceive in the Red Wall. The communitarianism they push is a very particular, regressive kind of community: found families or communities of interest are not their bag. Too metropolitan and progressive.

Rather than lead with the kind of economic radicalism we need, they lead with the kind of social conservatism that we don’t.

It feels like underneath this is a reticence – perhaps an always-already capitulation - to centre-right economics that will do nothing to address the fundamental inequality which proceeds from our economic systems. Without leading with greater economic equity, and the radical approach that needs, social conservatism is all that is left. Just as the Tories harp on about trans people and migrants because they cannot countenance economic justice, so too do Blue Labour because they fear their hypothetical electorate cannot either.

Perhaps buried in this is also a knowledge that economic decisions would not be under their control: globalisation means that economy is largely insulated from policy and politics. And yet, in their railing against the effects of globalisation (like migration), they simply tee up demonisation of one set of its victims by another.

There may be evidence that the Blue Labour is gaining a foothold in the party’s thinking. And perhaps this is what we see in Labour’s most recent twist to the right on migration. It’s not new: Blair and Brown took this turn too. Whenever Labour fears it is losing their original historical and ideological heartland of working class people, they, like Trump, and all far-right players who woo this demographic, have to find a scapegoat. As they try to harness these forces of hate, they soon find that they can’t control them: because there will always be someone willing to go further. So we drift and slide continually to the right. In Labour’s inevitable slide rightwards, Blue Labour or not, we also see mirrored the trajectory of the Tory party. Everybody slides right because they know that economic changes are unthinkable. Other things must stand in their place. Expect bathroom wars or other demonologies.

All of these parties need to learn from history: that we cannot use reactionary politics tactically without unleashing a force which is way older than politics, and indeed, than humankind. ‘Dealing with’ migration and focusing on the family, or giving communities ‘control’ will not fix the fundamental inequality that has driven working class people’s anger. If Blue Labour has its way, inequality of wealth will sit alongside a dangerous facsimile of a nostalgic English Eden that never existed.

They are not socialists of any sort. They are just reactionaries through and through.

Adam Something lays out the current US political situation

I have a good clutch of smart YouTube progressives I follow, and one of my favourites is Adam Something. This guy is so smart. He also has a cute cat.

He very cleverly outlines the current mixing together of three camps in the US Government in his latest video: the Fascist, the Corporatist, and the Incompetent. The fascists are the Christian Nationalists like J.D. Vance and the Project 2025 crazies. The corporatists are the Musk and tech bro carpet baggers. And bringing them together - an absolutely vital bridging piece - is the incompetent Trump, RFK, and similar useful idiots. (Indeed, Musk may be in this camp too, perhaps all three.) But without those incompetents in the centre, the corporatists and fascists wouldn’t have enough in common - so they need this utterly chaotic, useless, dipshit class of l defectives like Trump and his friends to hold it all together.

What Adam (I can;t call him ‘Something’) reminds us is that movements of this type are always a yoking together of interests into a specific leadership class at any one time (Marx talked a lot about this ). Authoritarian regimes are about bringing together different parts of society who demand power, and linking them with some kind of brute force with can bridge them. It rarely makes full sense - just like Thatcherism, Hitlerlism, Mussolinism, and Putinism don’t fully make sense as rational entities. What they are is just a bunch of people who want things, who find a way to align to get what they want. What they are very good at is agreeing with each other, and, at least at the outset, setting aside their ideological differences to get what they want practically.

As Adam Something points out, on the progressive left, we are terrible at this. He’s quite right, I think, that Bernie Sanders’ fairly mainstream brand of social democracy, and plain speaking, pragmatic thinking is what we need. The ideological purity of identity politics, or the ‘American diabolism’ (great expression) arguments you find on the internationalist left, or even the remaining crackpot Marxist Leninists he calls ‘Tankies’ (I think he’s seeing this from a very Eastern Europeran view - they barely exist in the West) simply can’t create a broad-based movement because all they care about is purity. Corbynism all too often strayed into this arena - whereas I think John McDonnell, and to an extent, Andy Burnham latterly, have a much better understanding and offer.

Anyway, take a look. Smart stuff. (Tip: he’s really hard to understand because he speaks very fast with perfect English and a Hungarian accent. Slow it down to 0.7 speed and it’s a bit easier!).

And finally: Some favourite memes and such-like

From the National Lawyers Guild in Detroit, USA: legal advice for activists.

See you all in a couple of weeks. I’ve been working on stuff about austerity and the welfare state which, sadly, I think is going to be very very topical….

Barely Civil Society is trying to create deeper debate in the UK charity sector.

Here are three ways to help.

1. Subscribe

To make sure you get new BCS posts, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Barely Civil Society is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

2. Share

OR….

See more at: https://www.civilsociety.co.uk/news/uk-s-wealthiest-1-donate-8bn-a-year-researchers-estimate.html#sthash.hE5ayaqf.dpuf

Note: ‘TF’ did not stand for trusts and foundations in this case.

I see this stuff all the time of course. I play games to make it interesting: every time I find a horse-related charity, I clop some half-coconuts on my desk and make neighing noises. Every time there is a Baroness or someone with a double or triple-barrelled surname, I do the same.

See Ruth Wilson Gilmore 2007 in The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex.

My first job in the charity sector was shaking cans for Kidney Research. I was terrible at it. I had a colleague who would shake the can and shout ‘Kid-NEY’ with an almost threatening rising intonation. He made a fortune. But a fairly common experience was someone coming up to me and demanding to know if I was paid. I was. I felt ashamed. I learned early that we shouldn’t be spending money on fundraising.

And the more we ask the ‘public’ to donate through individual giving, the more I worry that we are simply placing the responsibility to plug the growing gaps in our society’s social infrastructure on the people who have had the wealth extracted from them already by those who have avoided paying their fair share. Just like successive neo-liberal governments (like our current one) constantly picking the pockets of working people, many charitable demands for individual giving simply pull us away again from the fact that massive unfair income distribution causes the worst of the social issues charity is still called upon to solve. I’m really uncomfortable with public fundraising for anything other than the joyful nice-to-haves.