Is it time to retire trustees?

New research on charity trustees shows things aren't changing much. But does the model itself prevent change? Plus, Labour's crossroads: how can they combat Farage's insurgency of incompetents?

The funny personal bit

Well, that was another bracing week. F*ckface Farage gets more press. Multiple places in local elections in the UK chose to essentially befoul themselves in the electoral version of a dirty protest, just to show Keir Starmer. Sadly the rest of us have to put up with the stink of sitting next to them. Still, honestly, most of us would prefer that to sitting next to Kemi Badenoch. More serious analysis coming later.

That has at least taken some of heat out of the press’s triumphant crowing over the Equalities Commission’s advice to check your customers’ undercarriage before they enter your bathroom. I’ve been trying it with my houseguests this week, and while my plumber just thought he’d got lucky, my Auntie Mabel was really freaked out.

But it also turns out she’s my Uncle. You see! This is why we must always be vigilant! You can’t trust these people! Imagine, all that time, she has been secretly ‘seeing a man about a dog’ with the wrong equipment right under my roof. This is disgusting, and deeply disturbing, because…

…actually…

No, wait… I’ve got nothing. Frankly, it just seems like it’s none of my business. BECAUSE IT ISN’T.

This week: research from Pro-Bono Economics about the Charity Commission. And a little look at Labour’s impending lurch to the right in order to head off nasty Nigel at the Prejudice Pass. Which, you won’t be surprised to learn, ain’t going to work.

Coming soon: Trans rights and the history of the AIDS crisis. The long-promised update about the sector and how grantmakers are structuring their programmes based on changing situations. Watch this space.

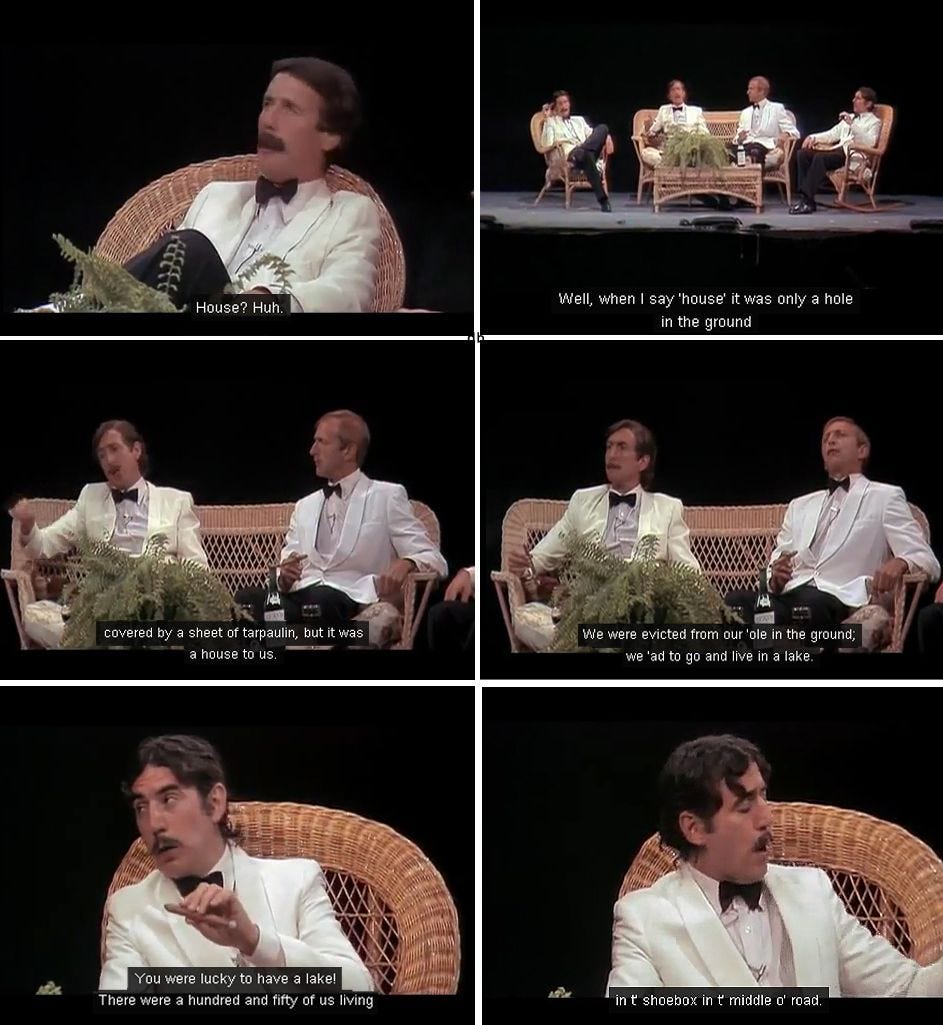

This week we are visually accompanied by Monty Python, which will be old hat for the old people, and possibly just baffling for the young people.

Before you read it, remember: there are many ‘good’ trustees. But the question is whether 'trustees’ are good.

Is it time to retire trustees?

Voluntary trusteeship the ‘lynchpin’ of public trust in charity, Charity Commission CEO warns Emily Harle, Third Sector, 30th April 2025.1

“Holdsworth cited new research by the commission and Pro Bono Economics, […] one in three trustees were invited to join the board directly by the chair.

“Of course, informal networking and personal recommendations can be invaluable, especially when charities are stretched for time.

“But this may come at the expense of casting the net wider, to recruit trustees who could bring different skills and perspectives to the board.”

Holdsworth said that looking beyond existing supporter bases, with fair and open recruitment practices, would help the sector engage a broader pool of trustee talent.’

This week, the Charity Commission published the research it commissioned from Pro-Bono Economics on trusteeship. CEO David Holdsworth had some vital things to say about diversity and recruitment - we must increase the diversity in our trustees. But it’s not just about recruitment: you can recruit all you like, and change your practices as much as you want. It’s not just about who we pick, but also, who picks.

Holdsworth also (as he has to), said many kind and encouraging things about trustees and their selfless devotion to communities. Well, perhaps. But sometimes I think it might be time to stop flattering trustees quite so much. I am becoming slightly frustrated by trustee boosterism.

One constant line

We tend to talk about diversity and our problems with/ approaches to recruitment - but there’s an even more fundamental problem with trustees. It’s that in most cases they elect themselves. I don’t mean that they just recruit in their own image: I mean that existing trustees, including outgoing members, are voting in their replacements. If your charitable funder, for example, has been around since the 16th century, there will be a direct lineage back to the original bunch of poshos who got their mates or family members to make decisions since then. Every single person elected by the last. How can we expect change that way? Imagine if that was how governments worked. (Okay, pipe down those of you at the back who just said they do.) This is even more the case when, as Holdsworth notes, a large proportion of trustee roles are still recruited by a tip and a wink from the Chair.

The point is that most charity governance was originally designed in that way to ensure lack of fundamental change, to make sure that poor people don’t get any funny ideas, and to ensure that people who aren’t ’like us’ don’t get inside the tent. Meanwhile, increasing diversity is necessary and vital, but in such cases, the likehood is that you will only elect ‘diverse’ people who may not look like you - but I bet they’ll think like you. That’s exactly what people screen for in those interviews.

Exceptions abound - but the figures speak for themselves. And I know that some organisations have different approaches. Most don’t. My take: you won’t be surprised to hear, but…. charities require radical change, and part of that *may* be that it’s time to retire trustees. I say that only because without even countenancing that, we may never even consider that everything we see as the ‘natural fact’ of charities is born out of specific historical conditions. I wrote in last week’s BCS about the role of the ‘Establishment’ in the Charity Commission. That is where it gets ‘writ large’. But a similar pattern is written into the very structure of most individual charities and their governance.

This week, I’m diving deeper into this question, and into the deeper structures of trusteeship. Class plays a central part in my analysis - because it plays a central part, historically and culturally, in trusteeship.

What is changing?

This week’s research commissioned by the Charity Commission confirms what many of us already suspect: trustee boards still look startlingly similar, demographically and culturally. That’s because they are precisely structured to reproduce themselves.2

The research shows most demographics are going in the right direction in terms of representative of diversity, although slower than we would like.3 More women across the piece. Smaller charities have more women (those charities have lower status and power, so go figure. But then again, I think they are the real charities). Ethnicity doesn’t look great - still less than half of what you would expect compared to national population. Of the younger trustees there are slightly more (specifically) Black people - but that probably just represents the generational change in the population itself.

Perhaps the least surprising factor is the massive predominance of retirees. We can all celebrate this as a triumph for older people still having value to society, and for voluntarism. Or we can look at it as a sign that only retirees can possibly give the sheer level of input trusteeship requires, and indeed the likelihood of having the level of skills and experience required and expected, given the sheer weight of legal requirements. We can also question whether this in itself is a barrier to changing and improving representation.

What isn’t changing?

As in the case of the Charity Commission, as we saw in the last edition, many trustee boards reflect not just structural inertia, but an entire worldview about who gets to lead, who deserves charity, and what kind of change is allowed. So even as the headline numbers on gender or age slowly shift, the deeper structure remains. It’s all about preserving that cultural and socio-economic hegemony through a solid set of establishment figures. That doesn’t mean, incidentally, that all trustees are bad people - it means that the system and structures will further structure and inhibit what is able to happen. They’re ‘structuring structures.’ At that stage, individual people don’t need to do it.

But perhaps the least surprising and most intransigent issue here is the numbers it provides on class:

Trustees still disproportionately come from professional socioeconomic backgrounds. Nearly six in ten trustees (57%) come from a professional background, compared to just over one-third (37%) of the working age population. I would imagine this massively increases as the size and status of the charity does.

By comparison, just under one-third of trustees (29%) come from a working-class background, which is lower than the percentage in the general population.

Household income reflects a similar pattern, with the median household income bracket among trustees being £50,000-£59,000, compared to £34,500 nationally. At least 65% of trustees are above the national median household income.

How could it be otherwise? We spend all of our time lamenting a lack of, and desperately seeking, ‘professional’ skills. That word ‘professional’ is a giveaway.

What do I mean by class? And why does it matter?

First, I want to be clear what I mean about class, and how it differs from the standard EDI focused definitions. It’s about a lot more than those figures - because they are one type of class, and a pretty decent way of identifying it - but they are not the whole story.

You may have noticed that asking people what class they are quickly turns into a Pythonesque contest as to who was poorer when they were kids. The fabulous Felicia Willow and I had a good chat recently about class in the sector, and thought it might be a good idea to feature it in a future podcast. But how to find people who wanted to identify as working class? She did a call out on LinkedIn, and within minutes it had turned into people telling stories of their shoeless childhoods. And everybody trying to find greater class authenticity than the last. ‘I was the poorest person in my school!’ ‘I walked to school on someone else’s legs, I couldn’t afford my own…’ ‘I ate my best friend’s face because it was cheaper than crisps’. And so on. I had to step away.

The point is, class is not a thing you have, it is a relationship in society, defined by your relationship to (social and -) economic production.4 As Marx argued, class is always changing, and class identities are being formed and disbanded. You can see this even better in things like E P Thompsons’s Making of the English Working Class - the word ‘making’ is the point. They’re created by identification. Think of it as people gradually thinking to themselves “Hmmm…… Those people seem to have the same interests/ needs as me…. Maybe I’m part of a we.” 5

The point is that people identify, whether they see it or not, things that bind them together socially and economically. And with that comes a set of beliefs and ways of looking at the world. If you choose a load of people from the same socio-economic class (as represented here by their income, and other background factors), you will inevitably find a general set of ideas they cohere around. There are always splits and schisms. Some will vote one way, some another. Some will be racists, some not. Some will like trans people, others will not. Some will be Black, women, queer. But the overwhelming shape of the dominant ideas will become clear over time. This is how ‘cultural hegemony’ works - the dominating influence on how people think through the ‘intellectual and moral leadership’ of the dominant class.6 In trustees and similar systems, especially when there is a lineage over the centuries, and especially given their abaility to elect themselves, you will undoubtedly select for ideas as much as status and skills. And at the same time, if you select for ‘professional’ skills, you are selecting for class - and therefore, worldview.

For this reason, we can see and hear it better than the numbers tell us. Here are some examples:

‘I think I should lead that, not the CEO. Otherwise, how will I get my MBE?’

- Chair of Berkshire welfare charity, Conservative Councillor candidate. (Failed.)

‘I don’t see why staff should get London living wage pay rises - we’re not a charity for them.’

- Head of Finance for multinational corporation, treasurer of local poverty reduction charity

‘You say you’re trying to reach local disadvantaged people and the poor - but what about the rest of us?’

- HR Director, train company, local poverty reduction charity

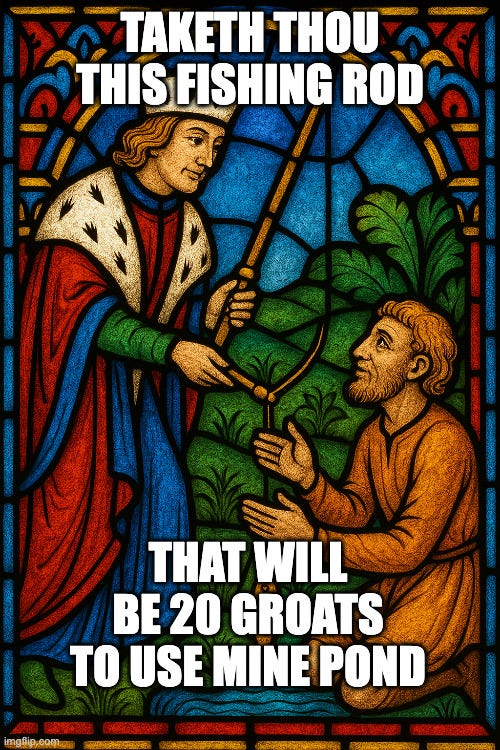

‘I don’t like the idea of just giving people help and not expecting anything. We need to teach a man a fish. People will become reliant on us.’

- Managing Director, telecoms company, trustee of education charity

‘I mean honestly, these charities are all so badly run, I was saying to Giles and Anunciata7 the other night at dinner, it almost makes you wonder if we’d be better off just paying taxes.’

- Tax avoidance expert, Big 4 accountancy firm, treasurer of homelessness charity.

‘I think it’s very good if charities have to compete with each other, because competition drives up good value and quality.’

- Hedge fund director, trustee of charitable foundation.

‘I don’t understand all those things you’re doing with people, although I’m sure they’re very nice. But it’s just not my area or my interest.’

- Finance director for a property developer, treasurer of a poverty reduction charity.

‘We can volunteer to show them how to manage their money properly.’

- Finance professional trustee suggesting trustees can personally educate clients using a food bank how to ‘manage their money.’

No, I am not making these up. (Note: all of them predate my consultancy career, and are not clients.) And I also know that some of these are outliers in their cartoonish arrogance - although it’s odd how many I could come up with isn’t it?8

Take just one example: my favourite. That is, ‘teaching a man to fish’ rather than giving him any of your fish. This is such a constant idea in the whole sphere of the social sector - it’s all about the danger of the ‘idle’ poor - a fixture of charity and welfare since at least the 11th century. But notice how much this is deep-coded into dominant ideas about the world in the dominant classes. I find this kind of notion constantly tends to reveal itself in trustees.

Trusteeship is failing trustees

The research also looks at perceptions and experiences from trustees. Trustees often rate themselves highly: 95% say they understand their role, 93% feel qualified, 60% think they’re having a positive impact. It would be unkind to widely ascribe this to the Dunning-Kruger effect, but the problem is that you don’t know what you don’t know. Constantly, over and over again, I have met trustees who have no idea what is required of them. Not the faintest clue. For some I have every sympathy - it is complex and unfair. For others, I have none at all - and it has often been the most entitled, professionally experienced, ‘great and the good’ who are the worst. They won’t even watch the videos on the Charity Commission website (which I think are pretty good). They assume they’re doing ‘the poor’ a favour just by turning up. Why learn anything new, when your social status is obviously qualification enough?

Finally, we discover that (only?) 38% feel more fulfilled because of their trustee role. This is unfortunate: why is it? There are lots of reasons in my experience. Some expect to arrive and run the show like a microcosm of their day job at the bank. I call them the ‘doll’s house tea party’ trustees. When they aren’t able to do this, they quickly tire of this nonsense and take their tiny pink cups elsewhere, for some stuffed animals that will properly appreciate them. Others – and I have much more sympathy here – arrive hoping for some kind of human connection. But what they get is a spreadsheet of management accounts (usually so so so bad) and a risk register. There are many other ways they could get that sense of real meaning and connection - but we funnel them towards our default ‘special door’ for the bourgeoisie.

And then there are those who, by some calamitous oversight of the establishment, are recruited, and actually don’t fit the usual trustee mould. For example, the ‘local person’ brought on for authenticity finds either that their voice is unwelcome – or that they’re simply drowned out by people with more confidence, more cultural capital, and more social power. Others just get no support at all, and quietly disappear. Often then the rest of the board reassure themselves that this is why it’s important to recruit the right sort of people….

So isn’t this system also failing many trustees?

Simple solutions?

Usually questions about how to ‘solve’ the problem of trustees (and which problem - that’s the real question…) turns into a debate about paying trustees, or how to do better recruitment. Paul Streets may be right to remind us that voluntarism is central to how real charities function - but at what cost, and is that necessary? And surely unpaid work vastly disadvantages anybody reliant on wage labour to earn their living? David Holdsworth is right that recruitment processes matte: not just appointing the guy you met at the Rotary Club is one thing. But appointing for skills, and indeed, for ‘fit’ will do exactly the same.

And neither of these address the deeper problem: the trustee model itself is built on foundations designed to exclude, drawn originally (and all too often today) from an army of dilettantes who want to be ‘overseers of the poor’ (essentially the original formation of what we now call trustees). Until we face that, no amount of boosterism or policy tinkering is going to cut it.

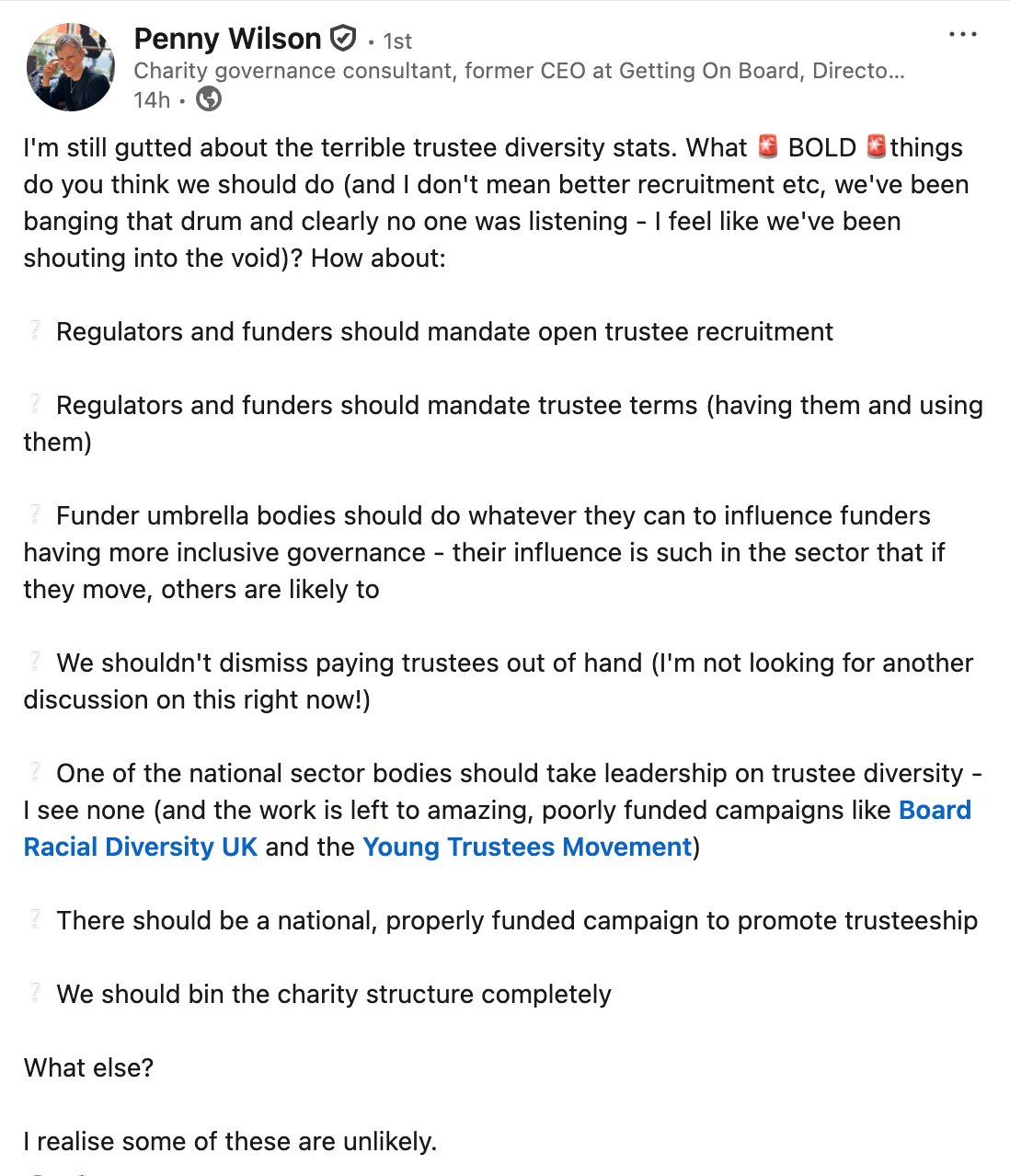

Penny Wilson, former CEO of Getting on Board (the charity to increase trustee participation, which sadly closed last year) also agrees that ‘better’ recruitment and paying trustees isn’t enough alone. (NB: it’s remarkable how much time is now spent lamenting the loss of Getting on Board by all the funders and key bodies who failed to give it the money it needed to survive….) It’s not like those things haven’t been talked about a lot. Maybe it’s time to think further.

Praxis: acting thoughtfully

So, I hear you cry, ‘what is the answer then? What would YOU do?’ Much as there are smart, dedicated people out there trying to find fixes for this, I don’t think quick fixes or policy tweaks are going to, erm, fix it.

I liked what economics campaigner Gary Stevenson said about this recently. People often say to him, ‘Well, let’s say we make you Chancellor, what would you do then?’ He points out that people have this idea that if you just get one or two brainy people in a room (pick any one of your usual suspect think-tanks, no doubt), you will come up with the ‘one weird trick’ (as they say on the internet) that will fix it all. But big change does not happen this way. Big change happens by long, iterative discussions, which begin with principles.

It’s interesting: in the microcosm, I see this all the time in strategy discussions in organisations, by the way. People come to believe they are in ‘analysis paralysis’ the minute anyone finds a problem that takes more than five minutes to discuss. They leave it for years and years, and never really address or consider the fundamental contradictions and conflicts, so that nobody even knows what they actually want - or what the problem they may want to solve actually is. They pride themselves on being ‘action-focused’ when in actual fact, they’re just being thoughtless and fearful of tough decisions.

That is writ large in matters of democracy and political change - far more complex than the workings of even the largest organisation. Big change takes years, is often incremental, and comes from rethinking your values. It comes from fully thinking about the problems, discussing them, and slowly but surely deciding what you want.

‘So’, you may say, ‘do we just do nothing until we reach the big answer?’

No, of course not. Every decision you make from that moment you begin to think is then pushing closer to that goal. In fact, the decisions - and the things they try, maybe fail, often succeed in - are both helping you do the thinking, and getting you closer, eventually, to the big change you want. But nothing valuable can be arrived at without proper, deep thought, which may even be ‘theoretical’. There’s a word for this: praxis. It’s the integration of theory, of big picture thinking, with real world ongoing practice. And it’s how people change the world - but it is a long, complex process which is decentred and must have time for debate and deep analysis. Not just a few workshops and policy papers - although they form part of it.9

We have to accept that mere boosterism isn’t going to be enough. We have to recognise that real problems won’t go away if we just pretend they don’t exist. We have to try things. I’ve made some suggestions elsewhere about some initiatives that will make a difference elsewhere, but hey, they are just the same kind of piecemeal initiatives of the type think tanks might come up with.10 But make no mistake, it does also require deep thinking about the real change we want to see.

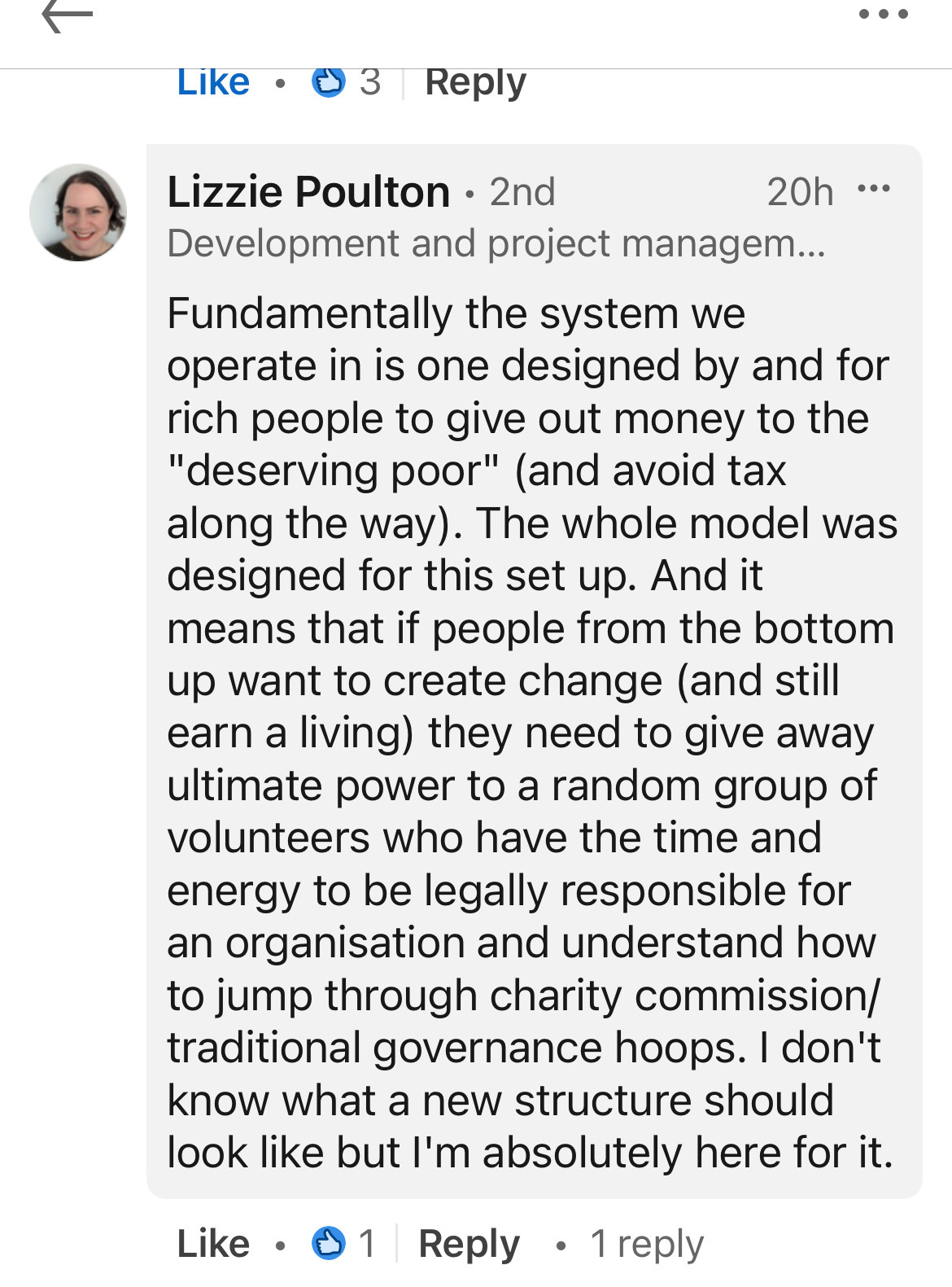

In this, I think all we have are the same problems you find in democracy as a whole. How much should it be representative/ indirect, and how much direct? Or even radical? And how much should it simply be a matter of people deciding to act, by free association? What balance of stability and renewal or change do we want to have? I think the thing is that we need different models for different situations and endeavours. And a bit of creativity perhaps. But I really cannot be doing with the model so beautifully described below by Lizzie Poulton, who wins ‘comment of the week’.

“Fundamentally the system we operate in is one designed by and for rich people to give out money to the "deserving poor" (and avoid tax along the way). The whole model was designed for this set up. And it means that if people from the bottom up want to create change (and still earn a living) they need to give away ultimate power to a random group of volunteers who have the time and energy to be legally responsible for an organisation and understand how to jump through charity commission/ traditional governance hoops. I don't know what a new structure should look like but l'm absolutely here for it.”

- Lizzie Poulton, Linkedin Comment.

She gave me one of those moments where I thought ‘Thank god, it’s not just me.’

Conclusion - or rather, the beginning

All of the questions here go far beyond the niche of charity governance. They are about how change happens in our society - and how we create structures that capture and reproduce certain ideas and ideologies. Fixes may (will) make it better. But we have to ask the deeper questions too. Democracy, change, and the power of elites to shape thought are worthwhile things to consider in charities. Theory matters. Culture matters.

And finally. There are many good trustees - friends, colleagues and comrades in arms. But again I look to the microcosm of organisations. As a CEO, when I’ve been looking at making big changes in organisations, I have always had to stress that restructures potentially leading to redundancy are about structures and posts, not people….

So you don’t need to email me or flame me on Linkedin telling me ‘not all trustees’, or about how you were so working class as a kid, you ate the family guinea pig at Christmas. I believe you, and I see you.

I cannot stress enough that increasing trustee diversity is of paramount importance. There are new organisations and measures afoot - please support them. Check out Kevin Taylor McKnight’s Queer Trustees group on Linkedin. And Action for Trustee Racial Diversity UK.

But we also have to ask questions about shapes, structures, and power - or nothing ever changes at a deeper level. It might be time to consider whether it’s time to retire - or at least fundamentally restructure - trustees.

Meanwhile, keep the ideas coming, and every time you make a decision, ask yourself: what would Peter Kropotkin do?11

Reform are donkeys in jackboots. So why is Labour following them?

Note: I included this on the paid subscriber version of BCS a couple of months ago. I want it to find a wider audience now, especially since already some of it is coming true.

The line below ‘And here come the bathroom wars and other demonologies’ was originally ‘Expect the bathroom wars and…’ No need to expect. Here they are.

And so Farage’s pet project, with its selected cretins designed to mirror the idiocracy across the pond, has swept the board, clearing up the Tories, and scaring Labour. As expected, Labour are already planning a swerve to the right. Because this is a party with no moral scruples and no coherent ideology, beyond bourgeois technocracy and neoliberal dogma, this is to be expected. And you can see the growing battle: idiocracy versus technocracy, warring versions of capitalism, with a waffer-thin mint of social progressiveness between them, when can dissolve on command for Labour. Because minoritised communities are always both expendable, and useful cannon fodder in the war.

Already, Labour’s lurch to the right was on its way. Expect the imminent return of Blue Labour, already in resurgence. They present themselves as the solution to Reform. The last time was when Ed Miliband took over the party. But it always re-emerges when the Labour party has a crisis of confidence of a particular sort. That is, when feels threatened by the right, and suspects that the best way to win over the working class people is to steal the moves of the nasty party and call it socialism.

At that stage, Maurice Glasman, (now a Trump supporter, and JD Vance’s pal) reappears to tell everyone that the reason left wing parties are failing is because they are too socially ‘progressive’. Blue Labour suggests we should ditch ‘social’ justice and multiculturalism in order to make the argument for economic justice easier to sell. What it likes to focus on is, on the surface, all the stuff I feel like I ought to care about given my VCS background: communities, local power, the value of small, etc. But you see, that can go very wrong. There is a kind of small-minded politics they idealise that is often nativist, anti-progressive, exclusive and intolerant, and far more concerned with levelling than flourishing.

The problem is, in many ways, what Blue Labour, and all versions of right-wing, socially conservative leftism are offering is Trumpism and Farageism with potentially more progressive taxation. It’s just populism.

But where indeed is that argument on the economy? The problem again is that Blue Labour’s solution to working class voters choosing the right is to mirror their opponents’ focus on culture wars. These guys claim to be centre left on the economy - whereas, we all know ‘real’ Labour is centre right (come on, let’s be honest). But the push on migrants, on the family, on ‘local’ communities here is more often dog-whistle politics for Reform voters - and worse.

And the communitarianism they push is a very particular, regressive kind of community: found families or communities of interest are not their bag. Too metropolitan and progressive.12

The problem for them, and Labour more generally, is that, rather than lead with the kind of economic radicalism we need, they lead with the kind of social conservatism that we don’t.

With Labour, we always find an always-already capitulation to neoliberal economics. It’s an unwillingness to address the fundamental inequality which proceeds from our economic systems.

Whenever Labour fears it is losing its original historical and ideological heartland of working class people, they, like Trump, and all far-right players who woo this demographic, have to find a scapegoat. As they try to harness these forces of hate, they soon find that they can’t control them: because there will always be someone willing to go further. You cannot out-Reform Reform. Because there will be almost no limits to how far they go. All you do is drive and quicken the curve to the social and economic right.

For Labour, it has already done irreparable damage to its brand, and the party increasingly realises the vast fuck up it made with Winter fuel payments.13 It fears it may even lose them the next election (I agree - it was truly the stupidest thing I have ever seen a new Government do since, um, the previous one, I guess). Benefits cuts will continue - a vote in June on those already promised, and apparently an even deeper set of cuts planned later in the year - and many in the party are terrified. It’s unlikely Reeves will back down, and they are scared to be seen to u-turn. All of this means it is even more likely that other totemic policies must stand in their place. Here come the bathroom wars and various other demonologies.

All of these parties need to learn from history: that we cannot use reactionary politics tactically without unleashing a force which is way older than politics, and indeed, than humankind. If Labour swerves to the right, with Blue Labour or not, an inevitable failure to truly tackle the inequality of wealth will sit alongside a dangerous fantasy of a nostalgic English Eden that never existed.

Labour under Starmer is, to nobody’s surprise, just one more neoliberal notch on the bedpost of late capitalism. But their last chance for any kind of redemption is to resist turning to the politics of hateful fantasy to save themselves. We already know who the victims will be.

And finally

Funny how much Monty Python has helped me out this week. Here are some videos of the full sketches. I think the thing for me is that these days, this isn’t really that funny - it’s just quite accurate satire.

Luxury!

‘We don’t have a lord…’

‘But eet ees only waff-er thin, monsieur….’

Barely Civil Society is trying to create deeper debate in the UK charity sector.

Here are three ways to help BCS make charity braver.

1. Subscribe

Barely Civil Society is a reader-supported publication. Please think about buying a coffee or even getting a paid subscription. It’s about a quid a week, for as many words as you get with most magazines. Or just send this on to your friends or mortal enemies.

2. Share

Linkedin recently changed its algorithm and is no longer showing posts for many VCS writers to a wide audience. (Unless you pay for advertising…) So….

OR….

3.

Trusteeship – a positive opportunity: Understanding skills, experience and demographics in England and Wales. Daisy Harmer and Antonia Ren, Pro-Bono-Economics, April 2025. https://www.probonoeconomics.com/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=62ddd0ba-3790-42ea-ac4e-d36620aff1c7

And your position will change too - my class position shifted constantly even before I was 20. My partner and I now have many of the trappings of the bourgeoisie but in many ways have never fully managed ‘entry’ - for example, both from working class backgrounds, but with ‘elite’ educations, and we lack ‘wealth’ even when we have comparatively solid income and professional status (well apart from the charity thing….). David Graeber puts it best: we are disappointed children of the socially mobile working class who discovered that ‘a bourgeois education does not automatically confer entry to the bourgeoisie’ - I’ve never felt so seen, and also sort of skewered….

If you’ve ever wanted to see what class change looks and feels like, just see what buying a flat does to your worldview and how you see property tax. All of my most leftist friends, if they’ve managed it, find their automatic thoughts about some aspects of economics and politics shifting the second they close the door behind them. Because you suddenly have a very different relationship to property and wealth. (How much so is a long discussion…)

The biggest class distinction it seems to me still is wealth versus work, and this certainly is the identity I think current leftist politics is cohering around. Property ownership is another (similar). But the point is, we create these identities based on the perception of shared economic (and social) interests. Those shared interests are ‘real’ and do pre-exist. But coming to awareness of them is the key thing for change - or indeed, for preventing change. This is what we call ‘class consciousness’.

The problem for social research and for workplace dynamics is that we’ve been taught in our somewhat primitive EDI heuristics to look at imagined essential qualities of individuals, because they are easier to count. It can just about work for gender, sexuality, ethnicity.Those are still all constructions though: for example, race isn’t something you ‘have’ either. It’s all a system of power and relations. Stuart Hall is a good place to look for explanations of this, but it’s a common assertion now in critical race theory. Check out this awesome video of one of his lectures on this subject. The guy is not just clever, he’s witty and much clearer in his talks than he was in writing (which is incredibly smart but very very hard going).

This is Antonio Gramsci. He is so so so hard to understand, I would definitely go with a reader to start with. TBH I find it as easy to understand in Italian in English and I can barely order a birra in Italy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/gramsci/

Only one of these names has been changed, to protect the not entirely innocent.

I cut it down from twice as many). And how many other people in charities can say the same?

It’s Marx! Bwah-ah-ah, sneaky socialism. Don’t tell the think-tanks.

I can’t find them - they’re in my posts somewhere. But, forthcoming…

Big hero anarchist communitarian and communist. https://daily.jstor.org/peter-kropotkin-the-prince-of-mutual-aid/

They are right that we need to focus on those communities who are voting for Reform. As Polly Toynbee put it, we need ‘rapid, highly visible action in communities and a forthright attack on the new right’. But when it all shakes out, I think we will get - a much cheaper - populism. The problem is, visible changes in communities are going to cost money. Reeves is ideologically wedded to fiscal self-mutiliation. And so the ‘visible changes’ are most likely to be on the news, in the form of checking winkies in bathrooms and gunboats trained on migrants. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/may/06/labour-local-communities-nigel-farage

‘No 10 rethinking winter fuel payment cut after Labour slump in local elections. Exclusive: government fears further electoral losses from unpopular policy as well as from planned £5bn of benefits cuts.’ Pippa Crerar and Jessica Elgot, The Guardian, 5 May 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/may/05/no-10-reviewing-winter-fuel-payment-cut-after-labour-slump-in-local-elections

I wonder, Alex, if we could align your thinking here with the “Nice Guys of Philanthropy” that I wrote about a couple of months ago. Did you see that piece?

Yes. Yes. Yes. On trustees. As one myself, nudging 50 this year, I am the second youngest and one of three women out of ten trustees and all are white. It’s a homelessness charity - I don’t have to go into the groups that are overrepresented in the homeless population that don’t appear in that board and for whom that board has not the slightest inkling that this might be to the detriment of everyone they give up their time to serve. I’m picking my battles with the dysfunction. Just not sure which one yet.