Queering civil society: a London Pride special

What can we learn from an LGBT history of love, care, and activism?

Hello, and welcome to a quick interstitial between part one and two of a longer piece on charity as an ethic. Related nonetheless.

This week’s BCS is personal and political. But the point for me is that politics is always personal. My originating community, and my connection to a historical and ethical lineage, comes through in everything I do in my work, just as much as my socialism. You’ll see why.

The not massively funny personal bit

This weekend is Pride in London. I stopped going to Pride some years ago when it became hen party for London and a parade for brands. But it has a personal as well as political/ identity significance for me. I met my partner 30 years ago this year at the very first Pride Scotland. A friend manoeuvred it so we were holding up either end of the banner for the university’s LGBT society. Our eyes met, our arms rapidly tired (those things are heavy), and that was the beginning of thirty years. There is a lesson to this folks: be careful what you get roped into when you’re campaigning.

To say that was a different world is an understatement. When you watch TV shows like It’s a Sin (which is set a few years earlier), you have to remember that Scotland was not London - in fact, nowhere else was London. When I arrived in Edinburgh, the gay bars had been closed by the Council. Fake licencing complaints were used to persecute a minority back into the closet. The gay scene had been swept away, and of course, had only previously barely been tolerated - homosexual ‘acts’ were only legalised in Scotland in 1980, 11 years later than England. The bars that were left were very different from the lively and wild scene of London or even Manchester. Leaving a bar meant the bouncer going out into the street to check both ways to see where the gangs were, and telling you ‘NOW!’ when they weren’t looking. From that moment on, you were on your own.

The lively and powerful AIDS activist scene in London didn’t exist either. This successfully drove queer lives back underground and made it tougher to organise. Don’t get me wrong: there were activists, and there was community care - but this was a highly conservative society with a deeply puritanical hatred of LGBT people. Pushing against that in an atmosphere of the shame and the silence of the closet make that much harder. Those bars, clubs, and cafes that managed to stil flourish in major cities allowed a kind of love and community power to be mobilised more explicitly. What remained was not exactly undergound, but quiet, cowed, closeted. As we know in our charities - communities need public social spaces to thrive. Scotsaid and others did great work, and the heath authority did vital stuff. But whereas AIDS in some ways led to the flourishing of queer activism and community in urban centres like London, New York, and so on, in a place like Edinburgh it was much harder. What did happen is all the more impressive for it.

When I arrived in Edinburgh, knowing it was centre of theatre and arts, I expected a thriving queer scene like I’d seen on ‘Out on Tuesday’ the LGBT TV programme (which was so boring I would have got married to a woman just to never have to watch it again). Instead I found a place decimated by AIDS and anti-queer violence, enlivened once a year by three weeks of festival. Believe me, it was better than where I’d come from. But there was no question that this was a dark place and a dark time. But early stirrings in 1994 eventually led to Pride Scotland in 1995.

When the first march happened, it was still actually scary. I remember the weird mixture of anxiety and excitement. We truly had no idea what would happen. Fundamentalists handed out 'Chick tracts’ about hell and paedophiles; the support of the police was not a given; religious groups announced on the news that they were praying for rain to wash away the parade, and in the place of the gawking straight folks hanging around the edges, were shadowy gangs waiting to find those of us separated from the pack. I’m not making this up.

We were all excited and anxious. But we were also together. Our friend who later died of AIDS at the age of 18 a year later (yes, people still died of AIDS in 1994 FFS) had his first and only Pride. It was a day of milestones. That day, I met some of the first gay friends I had met since turning up to university. My tribe had always been there, but there was previously just no way to know it. The sense of there being a real place, a real community, and that we were real people - and a movement - was life changing. After that moment, Edinburgh seemed to come out of the closet. New bars opened. Groups felt more possible. It really did feel like we had claimed a bit of space. I guess it was… pride. I imagine there’s something of that feeling in Budapest last weekend. I hope so.

What people forget about ‘pride’ is where the idea came from and why that word matters. I heard a young Black straight couple in Catford talking about why gay people felt they were better than everyone and were ‘proud’ of being gay, when they weren’t saying they were proud of being straight.

First of all, I so wanted to tell them that the idea was drawn from US Black culture - ‘sing it loud, I’m Black, I’m proud’, as the chant went. Black people were made to feel second class, aware of their own marked, lesser status - especially in a society where apartheid was still an officially sanctioned reality until 1964. Taking back Blackness and making it a matter of beauty and celebration was a refusal of the dominant ideology of Jim Crow America: separate but not equal.

As for LGBT people: if you’re queer, you grow up ashamed. You know that every relationship in your life is at risk, and indeed, in the case of romantic ones, is a risk in itself. That your family and community could reject you if they knew this terrible secret. As you become aware of your sexuality, you know it is wrong and shameful; it affects how you learn about yourself in the world. There is a book called ‘The Velvet Rage’ which explores this,1 and I remember Will Young talking about it movingly. It is a very queer experience to grow up with this sense of a deep secret that if it is revealed could kill you, quite literally, then and now in many parts of the world. So ‘pride’ is a refusal of shame. It’s also a refusal of enforced secrecy, which is a fundamental way of keeping us excluded. By refusing to stay closeted, we forced society to accept us. We were not a dirty secret. As the Queer Nation chant went, ‘We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it. We’re here, we’re queer., we’re fabulous.’

Do we still need Pride in the UK?

As for Pride today, if we ever imagine it’s no longer necessary, let’s bear this in mind.

In England & Wales, there were 24,102 hate crimes based on sexual orientation in the year to March 2023.

There were an additional 4,732 transgender hate crime incidents

Gay and bisexual men remain among the most frequent targets of anti-LGBT hate crimes.

Three in ten LGBT people (29%) avoid certain streets because they don’t feel safe. For trans people, it’s 44%.

44% of LGBTQ people say they don’t feel comfortable holding their partner’s hand in public.

Over the last few months, the behaviour of the EHRC over trans people and their right to use bathrooms has verged on outright warfare on trans people. Their approach had already been called out by the ILGA (International Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association) in 2024, as had the vile hatemongering of the Tory Government. The ILGA also noted that the ‘UN Independent Expert on SOGI (IE SOGI) expressed deep concern about the growing toxic and hostile environment that LGBT and particularly trans people face in the UK, attributing much of the hate to politicians and the media.’ We’re still a target for hatred - and that includes from the state, even in a supposedly liberal democracy in the UK.

Don’t forget about the old folks

Something we need to remember is that a lot of LGBT people, those over 50 especially, are estranged from our biological families. We don’t have kids we can rely on later in life. The very idea of adopting kids was unthinkable until much later than people imagine (even if we wanted to). Remember this also means no grandkids or great grandkids of our own. I know this seems obvious, but people often have multiple, not just one generation, of kids they can rely on. Or indeed, for many of us, prejudice and suspicion has long cut us off from other people’s kids. As recently as 2008 I remember being watched very closely around a teenage male relative at, would you believe, my father’s funeral. Those accepting families? Those adopted kids? Not really for us.

Many of us found ourselves ostracised, or had to remove ourselves, from families and communities and friendships that wouldn’t accept us. Indeed, often situations were overtly abusive. Our loved ones were our chief persecutors. In the US, there’s a growing body of research showing what should be blindingly obvious - that older LGBTQ people are finding themselves much lonelier and less connected than non-LGBTQ people. This is not by choice. This is because of structural factors, and discrimination over the course of generations. Much as I’m about to sing the praises of queer community in history, it can be far over-egged. We don’t all live on Barbary Lane - many of us, especially once we’re too old for what remains of the ‘scene’ become very isolated even from our ‘found families’, if we were lucky enough ever to find them.

Sadly, last year, Opening Doors, the only UK charity dedicated to supporting LGBTQ older people, closed down due to lack of funding, despite many efforts to save it. Some of the trusts and foundations who had previously supported it even pulled their funding once they realised that it was in trouble. New funds being put into LGBT youth work are to absolutely be welcomed - but older LGBTQ people have a lifetime of prejudice, trauma, and exclusion to deal with. Housing, care, and health are all sectors vastly impacted by anti-queer prejudice.

And finally, something to bear in mind: I’ve talked about this with Linkedin pal Kevin Taylor-McKnight, as indeed I have with many other LGBTQ friends. Much as things get better, we’re all the product of our past and our experiences. It’s no bed of roses being LGBTQ now - but it’s even more of an issue for those of us who still carry around in our heads and hearts a world when it was so much worse.

Right: on to the main event.

Queering Civil Society

Last week, I looked at why ‘charity’ has become something of a dirty word. What I came to in the end was that we’ve turned charity into an industry and not an ethic. An ethic is a moral practice. If we see charity as an ethic, it comes to take in much beyond a specific industry. It goes far beyond being a legal vehicle or a collection of organisations. It becomes a way of life and a way of human beings relating to each other.

Some see this as a religious thing - faith, hope and charity. But myself, I see it as a Foucault thing. I see it as what he called a ‘practice of freedom’. Practices of freedom - the development of an ‘ethic’ as Foucault sees it - are based on reflection. And they are based on living and discovering a moral and ethical code through that practice. He takes it away from rigid moral codes given to us by, say, certain religious texts, but towards us all learning and doing - together - what we believe is right. This is not individual, it is social. For Foucault in his life, this was done through community: his burgeoning connections to the San Francisco gay scene, and the gay liberation movement. He saw queer people in the seventies starting to build their own notion of how to love and live together, and what mattered to them. Found families, new ways of doing relationships, love beyond the boundaries of a nuclear hetero family, and new ways of having fun (whatever anybody thought) were all to play for.

When AIDS decimated the gay community, and took Foucault, those practices of freedom were key to our survival.

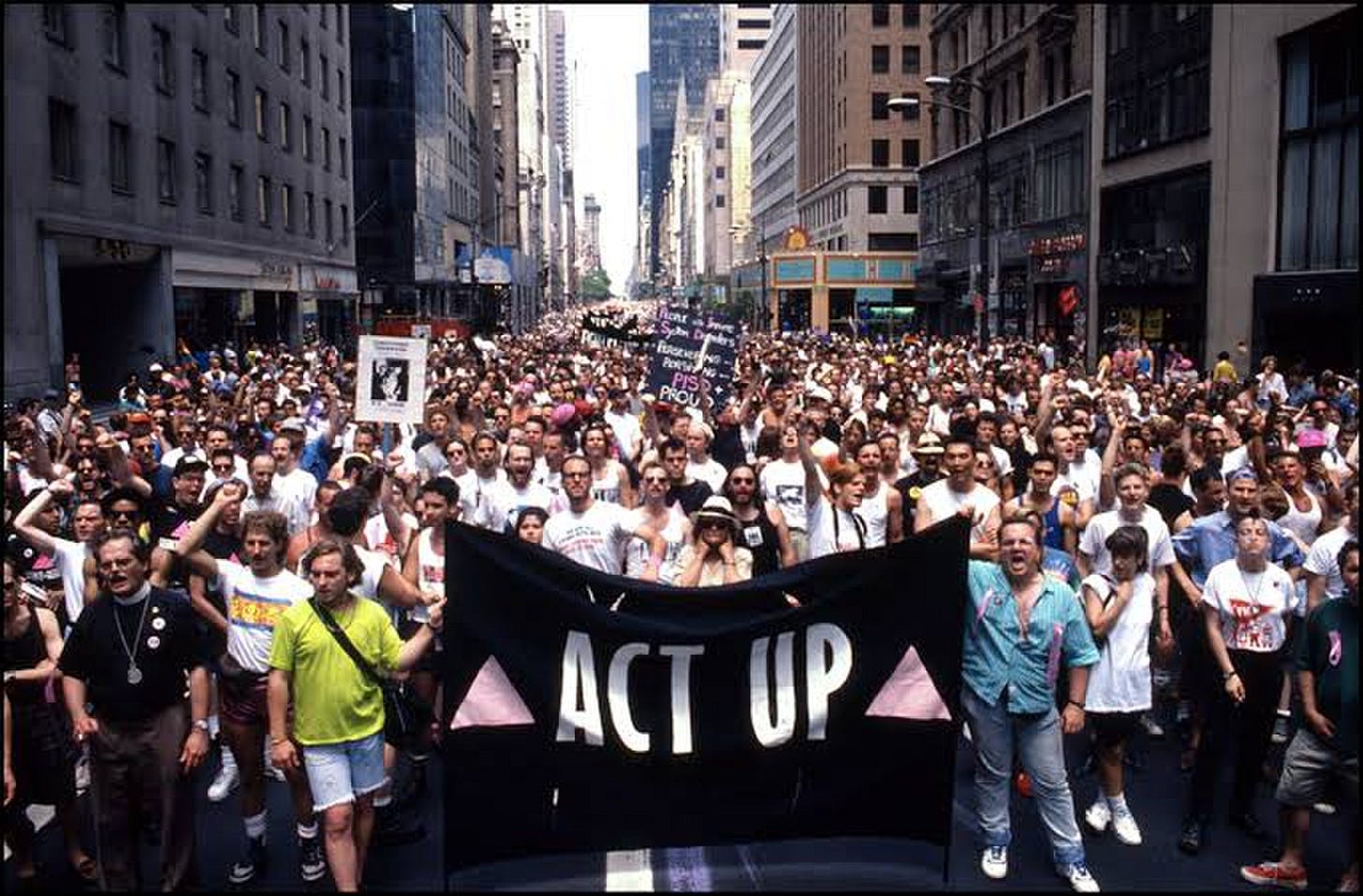

Our families abandoned us. Society shunned us and some called for us to be sent into quarantine and death camps. Many claimed that our deaths were punishment for daring to love. You can imagine how we might want to create our own ethic and practice of freedom given the moralities aimed at us. We chose community. We chose love. We chose solidarity and kindness in death and life. We also chose not to just be quiet. As radical democratic activist and organising group ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) came to teach us: Silence = Death.2

Our informal groupings became those kinds of radical democratic organisations, as well as rag tag groups who acted both in solidarity and on their own account. We centralised when we needed to, and did our own thing when it made sense.

We developed buddying. We shared lifesaving drugs however we could. Lesbians, feminists, trans people, fought for us, with us, and alongside us. (In case you don’t know, lesbians were first in line helping their gay brothers when AIDS hit. That’s why the ‘L’ comes first in LGBT. Not just because we’re scared of them and they’re handy with a pool cue.) In US urban centres at least, Black, Latinx and racially minoritised groups, queer and non-queer fought with us, and we fought for them. AIDS also ravaged their communities and allowed them to be cast aside by white Christian America. Sex workers and drug users too. These were grand coalitions of the marginalised: people who knew what it was like to be excluded, and were therefore radically inclusive, as they discovered what they shared, and built social practices around it.

We fought together to change the world, and we did. We harnessed the power of love and care and charity. Eventually we changed the world so much that some of us - but sadly nowhere near all - began to be accepted. We fought to gain the right to be loved and cared for not just by society as a whole, but by our own families and wider communities. These practices of love, care, and freedom set us free and created a new kind of world. That changed very specific legislations. We married if we chose to. We adopted if we wanted to. We could be ourselves. We joined with others in struggles to make the world better for all of us.

It wasn’t all a bed of roses

I don’t want to claim perfection. This is, for me, a personal foundational myth of my involvement in any kind of politics, campaigning, and charity. But I’ve studied enough about this over the years to know the faultlines here: queer organising and activism from communities rapidly hardened into much needed institutions which brought their own problems. Fundraising sometimes seemed to become an end in itself. Some argued that the growth of some of the largest LGBT AIDS charities actually undermined community participation by being turned into ‘giving factories’.

Elite capture was more apparent in the AIDS charity ‘industry’ than perhaps any other domain I’ve seen. There were many complaints that white gay men stole all the thunder of other affected groups - a very complex question I don’t have time for here. But ACT-UP in particular, for all its constant fissiparous, radically democratic and fragile allegiances, did an incredible job of bringing together activists from across the spectrum. And part of the problem is that the highly visible A-list Hollywood-style AIDS fundraising took all the media, despite the reality that it was everyday queer people of all stripes (include the majority of gay men) who forged incredibly cross-cutting alliances.

On the other side of things, ACT UP staged die-ins in front of the White House and displayed the body of a dead activist. It wasn’t all Elizabeth Taylor on the red carpet. And as time went on, we needed the schmoozy Ian McKellens as well as the shouty Peter Tatchells. We needed the radical as well as the more incremental types of campaigning; and the local and community-based care, alongside the nationalised, state-driven.

Stonewall, National AIDS Trust, Terrence Higgins Trust, all hail from this period and did amazing work. As institutions developed, and charities and trusts became (then-) solid and well-funded fixtures, this brought with it the danger of tamping down the radical fire of activism. As the public sector took on some of the work, or contracted it back out to civil society, the ideological drivers of mainstream society were taken on by many as the price for funding.3 In fundraising from the public, there were questions about whether to fund the ‘deserving’ or the ‘undeserving’. I still remember, even in the mid- 2000s, a local authority policy director telling me we should use the AIDS grant for ‘innocent’ victims like children. That was why our own fundraising was so vital. Things like the Red Hot AIDS charity harnessed the entertainment industry, both for money, but also importantly, for the power of the media to change minds.4

So there are many possible critiques, and nothing is perfect. Burying any of these criticisms is unhelpful, but so is focusing only on failures. All of these issues mirror the kinds of issues we find in civil society now: building coalitions; where our money comes from and how that affects what we do; the power of foundations and their accountability; some being left out by the changing whims of society’s generosity, and the shifting priorities of the state; the relationships between community activism and organising and formal charitable institutions; the relationships between activism, campaigning and care. And indeed, how much we want civil society to take on, and how much the state should take on. This question is central, not least given the delays in access to AIDS treatments in the UK, and ongoing horrific inequality of access to healthcare in the US. Nothing is simple. Everything is difficult. Everything is a negotiation.

For the future

We all learn about ourselves and our picture of the world we want to see through foundational myths, individual and social, and this is mine. It’s one I wished I had been a more direct part of than I was able to, and perhaps that’s partly why I now have civil society as my focus in work, and in writing. It’s not entirely unintentional that I presented this with some breathless story time awe - I want you to feel how I feel. I hope you have your own myth.

Much as I understand that some of my pictures of that time and movement are nostalgic, they are also utopian and very much future-focused. The only thing still to play for is tomorrow. Nothing is final, and fixes aren’t enough. We need to stay inspired and fight for that future we all deserve.

If you look at the start of this story and trace it to where we are now, I think you can see some sense of what might be possible in many other things. When my partner and I stood on Prince’s Street in 1995 and asked each other (in the context of a current news story) ‘Do you think they will ever equalise the age of consent?’, another friend said, ‘Yes, of course. And we’ll be able to get married. And we’re going to adopt children too.’ We thought he was out of his gay old gourd. But he was right, we were wrong. I know these advances have not benefited all equally, but that is a reason to continue to be inspired by them, not to discount them.

And it is with no small amount of anxiety that I note how easily these things can be taken away from all of us.

A real civil society

So, what I wanted to show, developing on from last week’s post, is a picture of a triumphant, real-world civil society. Organising and fighting together. Loving and caring for each other. Getting voices right there into the wider democratic debate, by whatever means necessary, and demanding change in society. Playing together and having fun. All of this across boundaries and against toxic mainstream ideologies. I think this can help us clarify and expand our definition of the work we do in the ‘charity’ sector - and civil society as a whole.

None of it is easy, and there are countless faultines as we go, but we need an ethic of care and love, and a drive towards freedom. With that must come a radical passion, and a fiery fury that refuses to rest at piecemeal change. As ACT-UP taught us, a bit of rage can be very powerful.

‘The Ballad of Tommy and Joey….’ by Carter Vail

Trusts cannot be trusted

Speaking of rage:

“After 16 years, last week the Aberdeen Group plc terminated its Financial Fairness Trust without notice and sacked the CEO, Mubin Haq, the chair David Norgrove and all the trustees. The company says it plans to move in a different direction.”

Aberdeen Group has just abruptly shut down its Financial Fairness Trust, cutting off the funding it gave for social inequality research and dismissing its board without notice. Aberdeen Group plc (formerly known as ‘abrdn plc’) is a UK‑based investment and asset‑management company headquartered in Edinburgh. Listed on the London Stock Exchange and part of the FTSE 250, it manages around £511 billion in assets (as of 2024) and serves a wide range of clients, from retail investors via Interactive Investor, to financial advisers and institutional investors, offering investment funds, wealth management, and financial-planning solutions.

Sometimes there has been a naive belief that this was a sign that big finance could support progressive change.5 This was especially held up as an example because they tended to support progressive research with a special focus on financial inequality. But…. guess what.

Again, the move reveals how quickly corporate commitments evaporate under pressure or the whims of the controllers - especially with changing tides from across the Atlantic which are enabling and encouraging the dropping of ‘do-gooding’ signals. As Toynbee argues, this is a stark reminder that capitalism is never a reliable ally in tackling injustice.

This is what it’s important to remember: they were always only signals.

After a good discussion with someone this week about class in the charity sector, in advance of a forthcoming podcast on the subject, this is pretty much a slam dunk example.

The problem is, talking about ‘inequality’ in our society treats it like some naturally occurring disease, as opposed to a system, a structure and an active political regime. That’s why we need to call it what is is - capitalism. And class. So while they were happy to fund work on inequality, what got it in the end was something much more fundamental, which is what leads to that inequality: the power of the ruling classes, and their absolute control of wealth and resources.

Remember: trusts cannot be trusted. This shows where the power is, however much lovely data we get on a snazzy website, or special groups are set up to promote their work. As delightful as some of the people may be who run them, many of the people and organisations who fund some of these trusts are among the scummiest human beings on the planet. Those who own the resources are always in charge. Don’t be drawn in.

I loved what Mike Zywina said on LinkedIn, referring to Abrdn’s naming practices: ‘fck cptlsm’.

In two weeks…

Join us again for Part two of Beyond Charity….

And finally…

If you want cheering up, follow Zohran Mamdani on Instagram.

Barely Civil Society is about making the make the nonprofit world braver.

Here are three ways to help.

Subscribe

Share

Support this research

If you donate, you can help me spend more time researching and writing - including some bigger projects I’m working towards. Could you buy me a coffee?

Send me a message

The messages people send me every couple of weeks are my favourite thing. Drop me a line and say hi!

This is an important book, but take it with a pinch of salt, especially if you’re not a gay guy yourself. It speaks very much of a particular generation, at a particular time, in particular urban centres. What it says about development of gay subjectivity and shame in adolescence is powerful though.

When I say we here, I need to be clear. I wasn’t there. But it still feels like we. I hope you understand this.

The ‘degaying’ of AIDS, for example: if you can find it, Edward King’s ‘Safety in Numbers’ is a brilliant account of the development of formalised health care in the UK that lost something in its mainstreaming, as much as it gained from becoming a vital part of the system.

One of the fieriest and most intellectual activists of all (and my intellectual hero), Simon Watney, was CEO of this organisation. These were very wise and canny strategists who understood the value of multiple approaches, and indeed, took part in multiple types.

This segment partially summarised by AI. I’m tired. I’ve been off sick and I’m behind on work. Leave me alone.