The Charity Sector's Class Ceiling

Central, but unspeakable, class is the elephant in the charity sector's room

Saying the unsayable

In April, the EY Foundation published a report about class in the VCS. It was picked up by the Guardian:

UK charities hiring staff with ‘privilege not potential’, report author warns. Working-class people less likely to get jobs in charities than public and private sectors, EY Foundation report finds.

They argued that the sector was infsufficiently meritocratic, and shot through with class privilege. Some people were surprised and indignant. I wasn’t.

I've long felt there is a glass (class) ceiling in the VCS. I posted a couple of think-pieces on Linkedin about this – with some trepidation. I do wish people were more open to the conversation. But the first few responses were pushback. Quite immediate, some quite sharp, almost indignant. Some were protective of the sector - this was just more mudslinging, and profoundly ‘unhelpful’. Another attack on our largely virtuous sector. (And I agree, we are attacked all too often…) And of course, people who identified as having come from working class backgrounds were among the first to object.

One respondent in particular noted that they too were ‘first in family’ (to go to university). Was I suggesting, they asked, that they have to put their class status on their Linkedin page? Erm, nope. Not least, because the idea that class is only a matter of significations - a badge of identity - is just wrong.

Another person said that they worked in a charity and had never had a problem. All their team were so supportive. Okay, I’m happy for you. I’m gay and people are nice to me in my local pub - but if I went round the corner to the one under the bridge, that would not go well for me. If it works out well for you here, great. But don’t deny what others experience - or are likely to experience in many places.

Other voices somewhat emphasised that the sector was hugely diverse - there are people from all different backgrounds, they said. Well, yes, of course there are. But I could say the same about society as a whole. The question is who is cleaning the toilets, and who is in the boardroom? Who is running the local corner shop and who is running Credit Suisse? Who has any kind of business, and who is employed on really shitty terms?

In the first couple of hours, I thought about deleting the post. Did it look like sour grapes of some sort? Who was I to talk about this (was I really even working class anyway? Not any more, no, of course not.) Was it just me making excuses for any failings of my own? Special pleading? And what indeed was my personal complaint, if any? And most of all: would it stop me getting work if I talked about this?

Me too

But then something changed. The comments began to show that there were a lot of people out there who understood this. Then people started messaging me personally to thank me for talking about it on LinkedIn. Saying they had always felt it and known it and they felt seen for the first time.

I felt quite moved, but also rattled. (Enough that I talked about it to my therapist…) A bit of anger I had tried to bury came up like a reminder of a bad breakfast. And there was that sense of shame that I carried with me, even with a working class background that had all manner of privileges plastered over the top of it (real privileges nonetheless). When I thought about it, I hadn’t had that feeling in local authorities or the NHS. I hadn’t felt it in, at least, small businesses. The places I had felt it most was in charities, especially around funders, trustees, larger charities. And of course any time I strayed towards ‘philanthropists’ or senior sponsors from financial companies. But even in the latter I saw more variety. I couldn’t help thinking that all of those were far more meritocratic than the sector I currently work in. And I wasn’t alone. I felt vindicated, but also more frustrated, having it confirmed. I really wasn’t imagining it. The post became very popular (by my meagre standards, at least). It was widely resposted. A lot of us were angry, and felt silenced – gaslit even.

It’s still about class

If we struggle to accept that social class isn't a real barrier to career development in charities - or indeed, to equity in many different aspects of the sector - it's worth asking the same questions we do about race, gender, sexuality, etc. There are plenty of women, BAME people, gay people, people from working class backgrounds working in charities. But what proportion of them are earning large salaries in positions of influence in national charities or funding bodies? That's why the notion of the 'class ceiling' remains vital here. I think we also need to remember that when some have succeeded with working class backgrounds, it's easy to dismiss the experiences of others who haven't been quite so lucky or successful.

Class is a continuum. People who want to deny it still exists often point to past, fixed systems based on absolute hierarchies. Those have been in decline for centuries, and most of all since the Industrial revolution. Often people point to the decline of the aristocracy as a sign that class is gone. But interestingly, philanthropy is perhaps one of the few places in society where the aristocracy and ‘old money’ still have a level of visibility. Noblesse oblige remains one of our greatest philanthropic drivers.

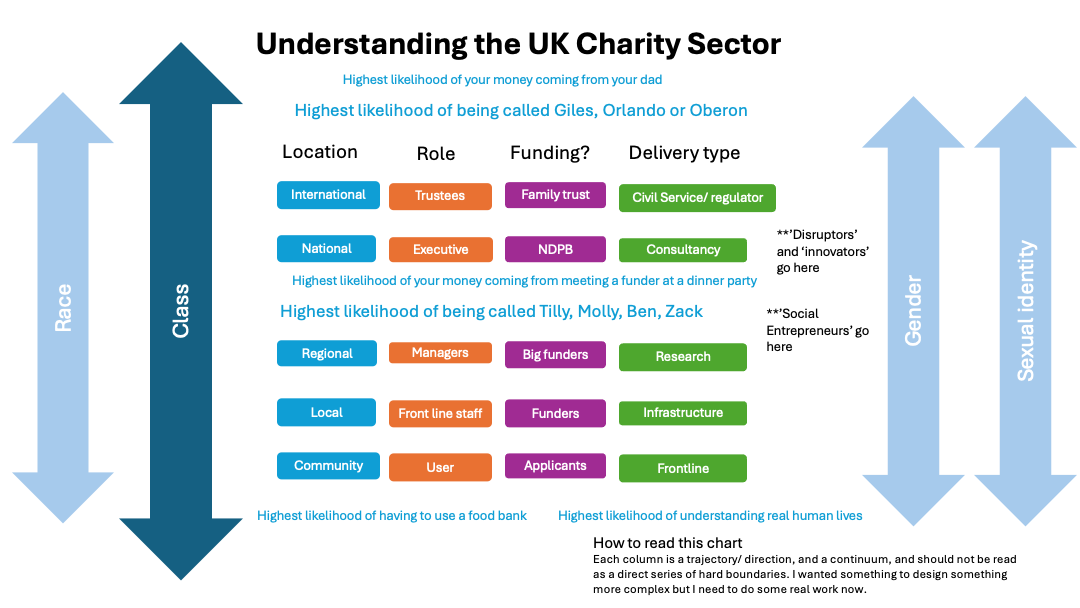

In this sector, there is surely an undeniable axis of class/ race/ gender/ etc, which sits alongside a parallel axis of local/ national; funder/ funded; leadership/ management and front-line; and employee/ trustee. This is a cross-cutting driver (and barometer) of power inequity between grantmakers and grantees; philanthropists and ‘beneficiaries’; Boards of trustees/ leadership and delivery staff; and very much between small, community charities and larger and national ones.

Whenever some of the larger, richer, charities affirm their commitment to ‘EDI’, I often ask how they’re going to get all these people from diverse backgrounds involved if they can’t even manage the odd person whose parents didn’t both go to university. Class is never included in any EDI programmes - and yet it is one of the most cross-cutting and intersectional of all issues. Not least on the matter of race, which oddly continues to elude meaningful purchase in the VCS, even while there are some small steps being taken in the public and private sector. This lack of attention to class is a significant reason.

Structuring structures

As Pierre Bourdieu put it, class is a structuring structure. It’s not just a matter of individual decisions and prejudice. We’re not talking about people being a bit snobby about working class accents - this is a structural problem which surely one would expect in a system essentially designed around the rich giving to the poor and needy.

Class is no more a simple matter of snobbery and judgement than racism is a matter of distaste for the colour of someone’s skin. Nor indeed is it a matter of any of the markers we use as shorthand (Did you go to a private school? Did your parents go to university? Did you go to Oxbridge? How much money do you have? These things are markers as well as deciders – but none individually can make the reality.) It’s a structure of oppression - a power structure, codified into meanings, enacted in practices, both the everyday and the systemic, and hard-wired into our culture and society - and not least, our economy, which both expresses and determines it.

It’s not just a personal or even a social/ cultural prejudice we need to challenge. The whole structure shapes what we can and can’t do - or at least, the likelihood we can do it. It relies on people doing ten times the work to get half way as far as people with half the talent. And to address properly, it we have to change practices and structures, not just force people to make the right statements or ‘check their privilege.’

Change in the sector

I’m as realistic on class as I am on race. Individualising responsibility to each organisation – especially recruitment - fails to take into account the reality of the macroeconomic and social structures which governmental social policy need to address. Education reform from pre-school to post-graduate. Income distribution. But certainly, we can’t just shirk the few things we can do. As a charity, it’s no use saying you are blind to class and then chucking out every application without a degree that you receive, or wherever the applicant hasn’t worked for household names. (Recruitment agencies are one of the biggest custodians of class privilege in the sector because of this.)

Saying we get a free pass because there are so many women in the sector is also unhelpful: the fact they end up in a sector with low pay and low status says a lot about our society, for one thing. And I went to meet a VCS research organisation the other day, which had thirty staff who, apart from the CEO, were female, under 40, and blindingly obviously upper middle class, not to mention white.

It’s no use saying you don’t judge on accents but then automatically putting people who have worked in the Civil Service to the top of the pile. It’s no use saying you want to nurture young talent from working class backgrounds and then paying wages so low they couldn’t possibly afford to work for you without external financial support. Or deliberately hiring working class people and then leaving them without any support so they just fail and you can say you ‘tried’.

And it’s no use saying you embrace people from working class backgrounds if you only accept people who have sufficiently internalised your values that they are now at the top of the pile - especially since they will now say that they got there through the sweat of their brow and they are proof that class no longer exists. As ever, so much of this could also be said about race and gender - it sounds like what Kemi Badenoch says about race (not about class, remember, she worked in McDonalds). But the last thing we need here is an oppression Olympiad of prioritising barriers, not least because the intersectionality of the whole thing is so powerfully overdetermining.

Does raising this mean I feel any less connection to, or passion for my sector? I was going to say of course not.

But I have to say it does sometimes make me question, every now and then, whether I have made a horrible mistake by working here. What seemed when I was 20 like a scrappy, anarchic sector where you could make some more direct difference, feels much different to me now. I wonder if I would make the same decision again.

As it stands, it does make me want to make it better, and to make it somewhere that practises what it preaches on socio-economic equality internally, as well as externally. That means we have to be willing to discuss it, just as we have slowly been doing on race and gender.

Links on Class

As a massive geek, I’m sharing here some links and books on class that I’ve found interesting recently, in case you’re interested.

Pierre Bourdieu - Distinction

Big hero of mine: Pierre Bourdieu. I always liked his take on class because it made clear how central culture is to class - and also that it is something that is both socially constructed, and internalised, and this is how it becomes that ‘structuring structure’. His ‘Distinction’ is readable as well as groundbreaking. Good explanations here of Habitus and Cultural Capital.

https://www.routledgesoc.com/profile/pierre-bourdieu

Richard Sennett - The Hidden Injuries of Class

This is the best book on classs I have read in many years - and I’m ashamed to say I hadn’t heard of it until recently, despite its hallowed status. A particularly memorable phrase (although I think he’s quoting) is ‘Social mobility creates social anxiety’. It’s a richly detailed qualitative study of working class people in Boston in the 1970s, and especially of those who have become educated, or moved into managerial roles. As he says in the introduction, in the days of Linkedin and Indeed, you’ll be surprised at how much of it could have been written today.

The Hidden Injuries of Class by Richard Sennett

Downward mobility

Social mobility has always worked both ways - my own social mobility went both ways repeatedly as a kid within a single generation, as did my partner’s and his family over the course of two. There has been recent attention to this around Millennials’ (and latterly Gen Z’s) concerns about the impacts of economic downturns on their own experiences. I think it’s worth pointing out that this kind of article skews towards a solely economic model of class (no doubt partly because, I suspect ‘Millennials’ as self-identified are almost entirely middle class and university educated). However, one of the core issues here is that, ever since university maintenance grants were removed, and tuition fees introduced, the ladders of social mobility have been pulled up. And indeed, even the Government admits that social mobility has declined in many ways, with equality gaps increasing.

'Downward mobility 'becoming a reality for much of British youth' (Guardian article, 2019)

Arline Geronimus - Weathering

Another fascinating book on class from the last couple of years is Arline Geronimus’ Weathering: The Extraordinary Stress of Ordinary Life in an Unjust Society. There’s an intervioew here with her. She tends to focus very much on race, but I think this is partly because race is a much more discussed and open subject in the US than class is. I found this when I was writing about class in academia too: whenever I strayed towards the US, people would always correct me to tell me I was surely really talking about race.)

Even Forbes believes in class now

We all know that class doesn’t exist in the US, and all you have to do is work hard and you can become a billionaire or president, or, probably, both. But even Forbes magazine hasn’t been so sure sometimes.

Forbes magazine: Overcoming the Class Ceiling at Work

The ups and downs of class

I found the below really interesting - first, because it’s true that working class people do occasionally go to private schools (not usually very happily, and more in the past in the UK when there were the Tory Government’s ‘Assisted Place’ schemes in the 80s [see the Sutton trust report linked here] - but charitable versions of that kind of work still happen). But also because somebody here has clearly then found that it doesn’t ‘take’ , and that downward social mobility is very real. It also links back to what Sennett (above) talks about - working class parents who strive to give their kids a top flight education in the belief that it will make them finally fully escape their roots. And yet, it never quite does that, because it’s about so much more.

My working-class dad sent me to private school – now I feel that I’ve failed him

Class Mobility

This is a really good Medium article - I like the mention of Barbara Ehrenreich’s ‘Fear of Falling’. Guillermo Gomez relates this to his personal experiences. I’m loath to do this myself, so I’ll let someone else’s story outline it. All our stories are complex. All of us are somehow inbetween.

The Rollercoaster of Class Mobility: Liberation, Anxiety, and Transformation by Guillermo Gomez

Ehrenreich - The Inner Life of the Middle Class

And finally, the motherlode, Barbara Ehrenreich’s ‘Fear of Falling’.

Just read it!