Beyond Charity. Part Two: beyond socialism?

What role could charity play in a world with greater economic equity?

Welcome to another week of Barely Civil Society, one week later than intended due to a family wedding in the middle of a field in the middle of nowhere in Norfolk. Seriously, what? What is it with straight people and weddings? Can we all please agree that a registry office in Zone 1 is the perfect venue, and then we can be home in time for bed with cat and the new series of Slow Horses at 9pm. Or 8.45 if I’m in a bad mood.

Having alienated 80% of my readers, let us continue.

Introduction

This week we take a look at part two (maybe three if you count the intermezzo of the queer civil society week) of my epic on charity as an ethic, and particularly, how that relates to socialism and desires we have for lasting systemic change. All this talk about ‘systems change’ never seems to consider the the actual ‘systems change’ that might make a difference. Perhaps this is because it seems unthinkable that we might have a remotely socialist Government even with a massive Labour majority. That shows how much the Overton window has shifted in 40, even 20 years. It also of course speaks to the politicised policing of charities and their permission to speak about ‘politics’.

In the meantime, it seems to me that we need to connect up charity with some kind of real political and economic change for the future. If you think this is ludicrous, you might want to stop reading third sector newsletters and get out a bit, where plenty of normal people see this as pretty obvious stuff: 43% of the UK population wanted some form of socialism as of 2023, rising to more than half in the 18-34 age bracket.1 You might also want to stop reading, because this just isn’t for you.

Beyond Charity.

Part two: Why charity needs socialism - which needs charity.

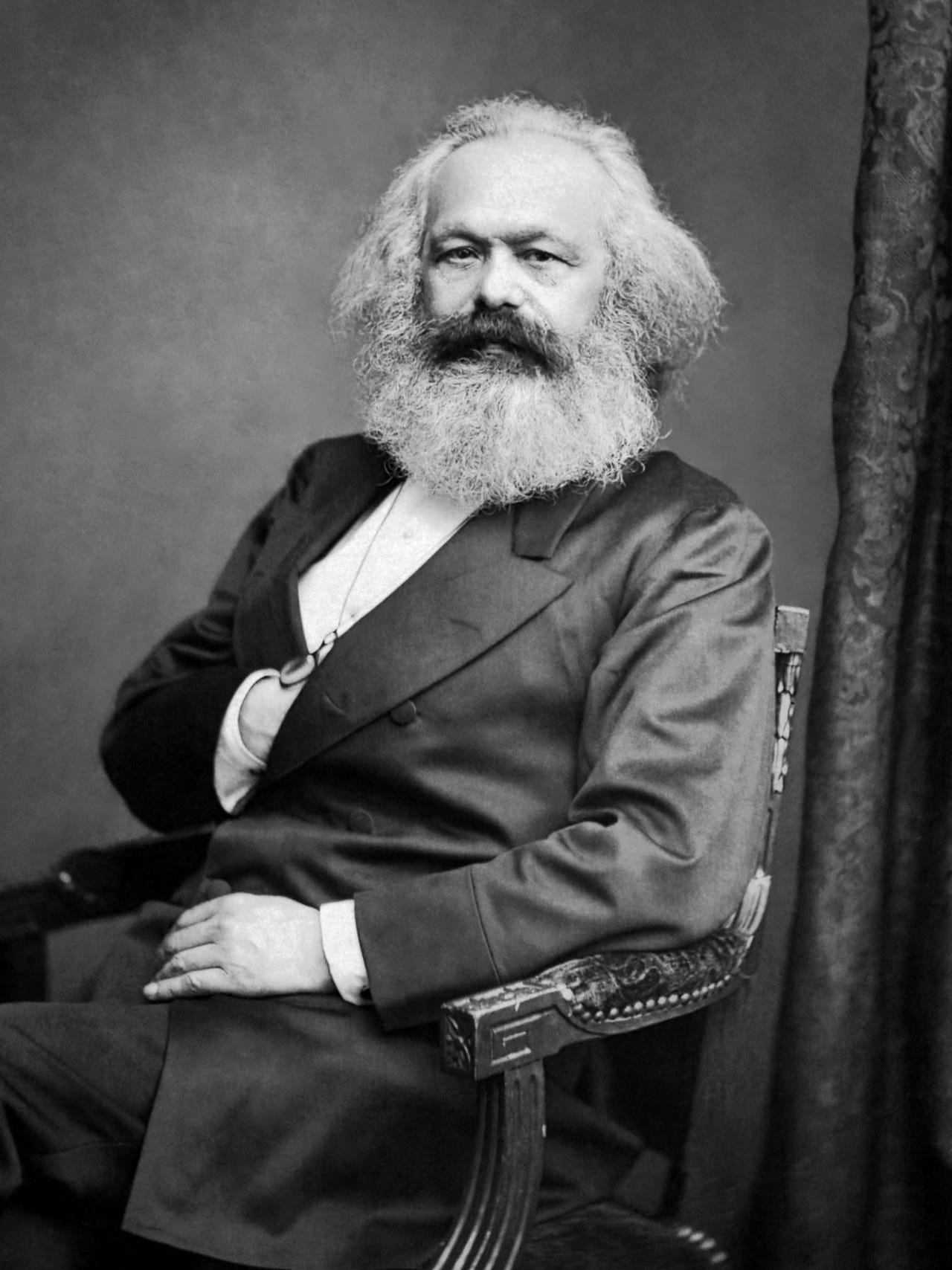

I've talked a lot recently about charities/ civil society/ nonprofits and socialism - with more to come. I've mentioned the deep sense of distrust that many on the left have for charities. Very often leftists still equate charity with almsgiving (donating material goods or money to unfortunates), geared towards sidestepping any fundamental redistribition of wealth, or putting the means of production (wealth being one in itself) into the hands of the whole of society. In this, they suggest a covert repression of the poor. Marx and Engels were scathing about charity, and for good reason, given their historical context.

They saw it as innately reformist and piecemeal. Worse, they saw it as a way of the bourgeoisie continuing itself and of reducing poverty - but by 'removing the disruptive or revolutionary elements'.

I’ve made many arguments here about the uses of ‘philanthropy’ for this very purpose. And indeed, I don’t disagree that this is exactly the kind of approach taken in theory by most modern discourse about charity in the mainstream. And yet, weirdly, I hear extremely different perspectives every day from people actually working in charities themselves. They see, and decry, its inadequacy. And yet, they also see the innate value in the things that charity is good at.

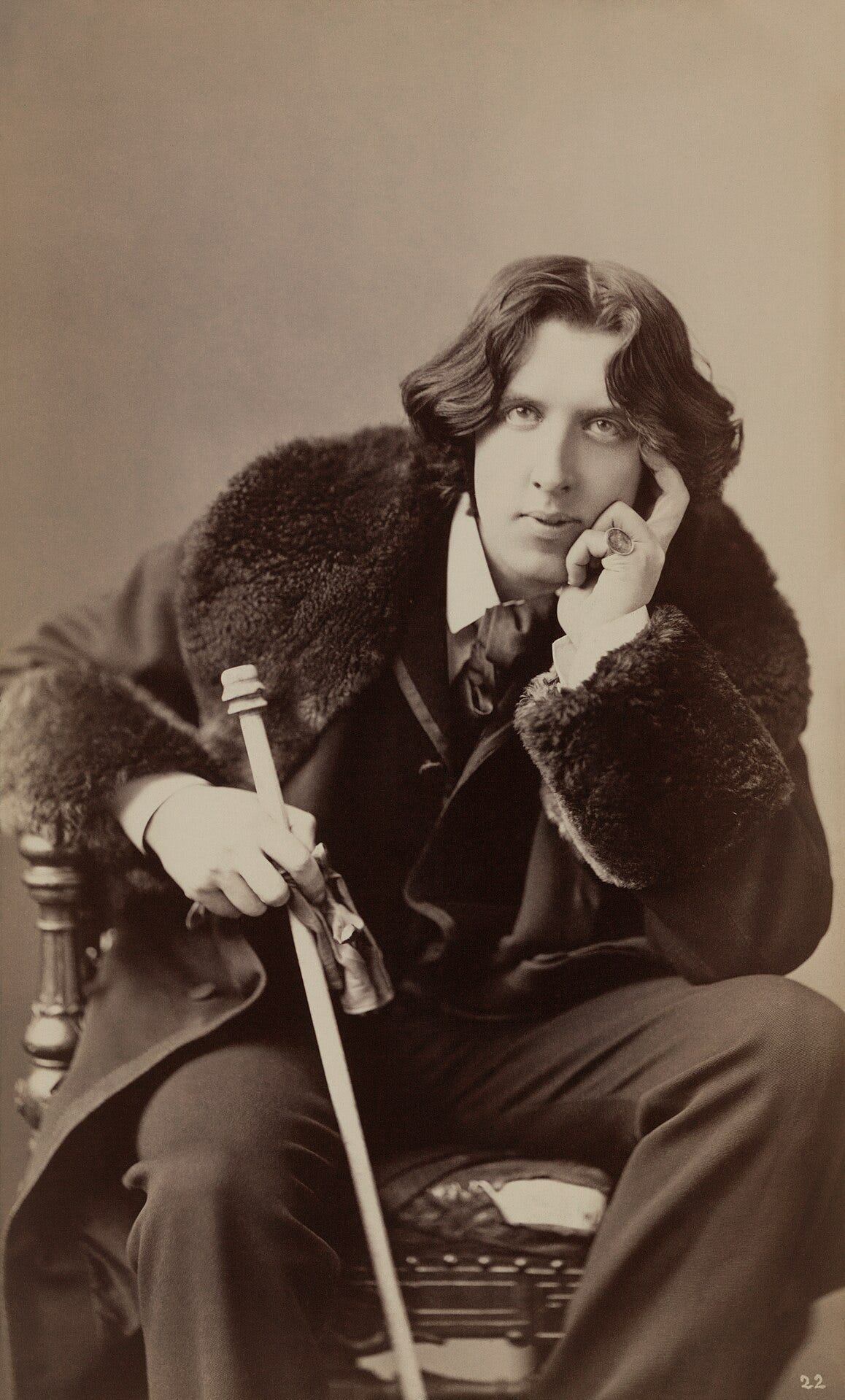

Marx and Engels were far from alone. More unorthodox socialists were equally critical. Oscar Wilde, writing 24 years after Marx’s Das Kapital, spoke scathingly of charitable do-gooders.

"They try to solve the problem of poverty, for instance, by keeping the poor alive; or, in the case of a very advanced school, by amusing the poor.

But this is not a solution: it is an aggravation of the difficulty. The proper aim is to try and reconstruct society on such a basis that poverty will be impossible. And the altruistic virtues have really prevented the carrying out of this aim. Just as the worst slave-owners were those who were kind to their slaves, and so prevented the horror of the system being realised by those who suffered from it, and understood by those who contemplated it, so, in the present state of things in England, the people who do most harm are the people who try to do most good; and at last we have had the spectacle of men who have really studied the problem and know the life – educated men who live in the East End – coming forward and imploring the community to restrain its altruistic impulses of charity, benevolence, and the like. They do so on the ground that such charity degrades and demoralises. They are perfectly right. Charity creates a multitude of sins.

There is also this to be said. It is immoral to use private property in order to alleviate the horrible evils that result from the institution of private property. It is both immoral and unfair."

— Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man Under Socialism

But what were Marx, Engels, and Wilde actually critiquing?

History: expanding definitions of charity

Clearly, what is considered 'charity' has expanded legally, and that indeed, mirrors and (perhaps also helps drive) the whingeing of funders, charities themselves, and the public alike that there are 'too many charities'. But the point is: when some kind of welfare state took over (for around 50 years) the support of the poor, and what we now consider basic public services like health and education (which of course remain supplemented by 'charities' like private health and schooling), there was room for wider public benefit to flourish.

Civil society, and the notion of contributing to a better world for all, by many different means, became possible, both legally and practically.

In 1891, the year Wilde was writing, the law on what was considered ‘charitable’ changed to become broader. Lord Macnaghten’s 1891 act (Mortmain and Charitable Uses) sets out charitable purposes as:

The relief of poverty

The elderly and the young

The advancement of education

(Incl. The nurturing of public taste in aesthetics, music and the arts etc.)

The advancement of religion

Other purposes beneficial to the community

Animals and their welfare

Public works and economic projects

Leisure and recreation in the interests of social welfare

That fourth one is known to this day as the 'fourth head' - a catch all that opens up wider social benefit. It has continued to expand. And this expansion became possible because of a fundamental shift in what charity could be, broadening out from the highly restricted three previous ‘heads’ very much focused on the role of almsgiving and support of the deserving poor.

Fast forward more than a century. By the Charities Acts 2006 and 2011, with case law changes becoming codified, there were now 13 categories, and the ‘catch-all’ fourth head remained. The fact that these latter changes were made during the reign of New Labour, who were broadly very supportive of civil society in support of the ‘Third Way’ also occurs in a time of comparative plenty, and when, despite setting the coordinates for a further marketised and highly neoliberal state that we are still struggling with today, there remained some belief that a properly funded (and respected), civil society could bolster a functioning, supportive, happier society, rather than simply plugging the gaps of a shrinking welfare state.

Overall, the most fundamental changes that happened to charity and our conception of it have been made as the need for almsgiving as an informal practice has reduced. The development of the welfare state and a form of some kind of socialism opened up possibilities: it made it possible for charity to come closer to civil society. At the same time, as governments in recent years have steered towards the neoliberal iceberg of austerity that even economists as mainstream as the IMF know leads to permanent cycles of decline, civil society has been pushed out of its wider role in society, back towards almsgiving, and monastic support for the meek.

This transformation reveals something crucial about the relationship between charity and socialism.

The historical context: charity as almsgiving

Let's remind ourselves of what charity's growth in England has looked like: essentially, beginning with the almsgiving of the poor usually through the church, later solidified by law, in which Tithes were used both for the upkeep of the monasteries, and for distribution to the poor. Alongside hospitals, much of this took the form of giving out food or small amounts of money to take the edge of the very worst poverty, for those who could not work. Later, this became the duty of states, albeit heavily influenced by the Church, with increasing levels of provision, and legislation, from the Elizabethan Poor laws onwards. Throughout this period, there were both the giving of sums of money, and the running of community hospitals. Later, the development of education and schools gained pace. More complex and developed societies, and larger economies with wider spreads of wealth and reduced monarchical and ecclesiastical control gave birth to the bourgeois civil society towards the 18th century. Here there was a broader notion of public-minded private endeavour focused on influence and discussion, as well as demand for social change, alongside continuing and increasingly organised private 'charitable' practices. But those aspects of social change that reformers spoke of would not have been seen as in connected to ‘charity’ itself until much later. At the end of the nineteenth century, with the growth of workers rights, the birth of the labour movement, and further moves towards basic social welfare, the purposes of charity were able to expand.2

The great transformation: when the welfare state changed everything

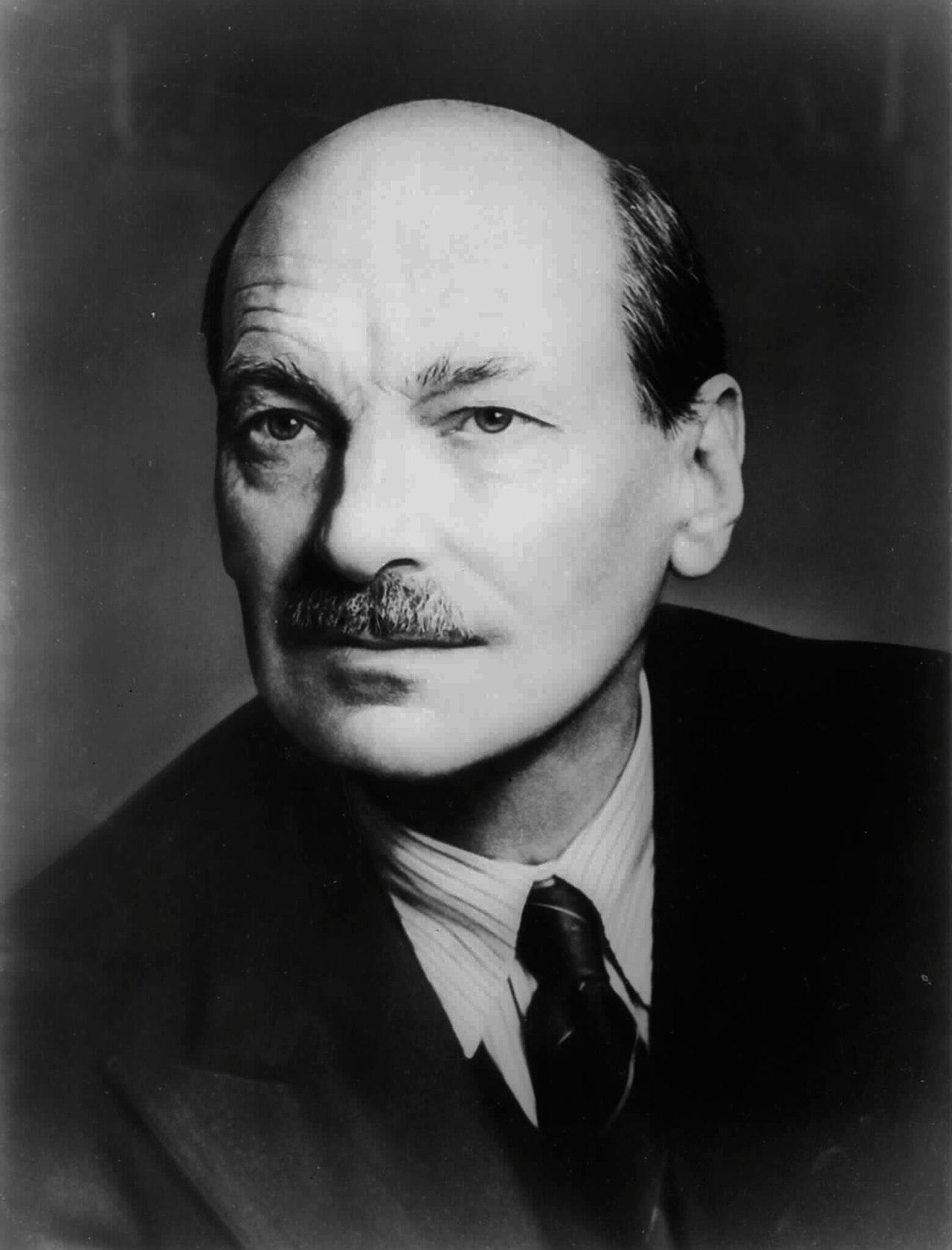

Further changes followed after the introduction of the welfare state. Charities went through a period of self-questioning: what were they there for now, if socialism and the state were now responsible for so many of their original purposes? But when we developed the welfare state, we didn't suddenly find there was no need for 'charity'.3 Remember that the archiects of the welfare state, like Clement Attlee and Nye Bevan, were people who had worked in poorer communities, based in charities, particularly settlements. They saw the ineffectivness of the localised and voluntaristic delivery of support for what we would now call ‘the vulnerable’ in charities - education; social care of the elderly and the young; help with health; redistribution of monies to help with living costs.

But in the new era, most of these organisations found renewed purpose and potential. They focused on wider issues: social cohesion and building community. They offered opportunities for education beyond formal schooling; leisure, arts, mutual support groups, and all the other kinds of things we have come to recognise as ‘charity’ in the modern Anglosphere.

They were also suddenly able to provide love and support and care on a non-industrial scale in communities. We should also remember that one of the problems with the industrialised healthcare and social care that the welfare state produced is a level of alienation. Massive hospital wards, massive schools, anonymous care, reduced community, increased dependence and reduced autonomy. These things are as much an issue with industrialisation as they are with capitalism or communism/ socialism. So ‘care’ in charities as practiced since the birth of the welfare state has offered an alternative to this, and put back some of what industrial level socialised care took out.

Why socialism needs charity

So, when Wilde, Marx, and other formative critics of charity were writing in the late 19th century, they were writing about something very different from charity as we would recognise it now. (Or at least, as we recognised it before 2010. As food banks and homeless shelters have grown again, we have seen a revival of private charity and almsgiving meeting basic social functions.) As states shrink during times of economic adversity (ie. when profits start to fall and the money needs to come out of poor people), we will tend to see pressures on both state and 'charity' to rebalance the 'biting point' of the gears.

Now let’s be clear: whether social democracy of the post-war consensus type is socialism at all is a complex question. Certainly, its goal of redistribution moved us in that direction, even if simple redistribution by progressive taxation is only a very weak form. Nationalisation of industries is closer to the socialist principle of socialising (holding in common) the ‘means of production’ (land, wealth, labour, material resources, knowledge, so many other things). But no matter what, the idea of holding resources in common, and distributing the products according to need rather than market alone, was a core part of the Keynesian approach, imperfect as it was. (Loads of Marxists have just printed out the picture of me from Linkedin and started throwing potatoes at it - sorry chaps - and I bet you are indeed mostly chaps.)4 As a socialist democracy with fairer distribution moves closer to reality, and as people’s basic needs are met, society is able to spend more time focusing on needs beyond food and shelter. And that, it is often forgotten, is the goal of socialism: human flourishing beyond basic need. And it is forgotten not just by those who present the goals of socialism as puritanical potato-bothering, but also by socialists of a certain type themselves.

Now, setting aside this sense of anxiety about the lack of focus on the human in socialisms of various types is part of a history if its development. Especially in the latter half of the twentieth century (but present from the start), there have been concerns about what some (in my view, wrongly) called ‘really existing’ socialism or communism. For example, post-war Marxists rapidly began to recognise the realities of Soviet communism and its horrific destruction of human lives.5

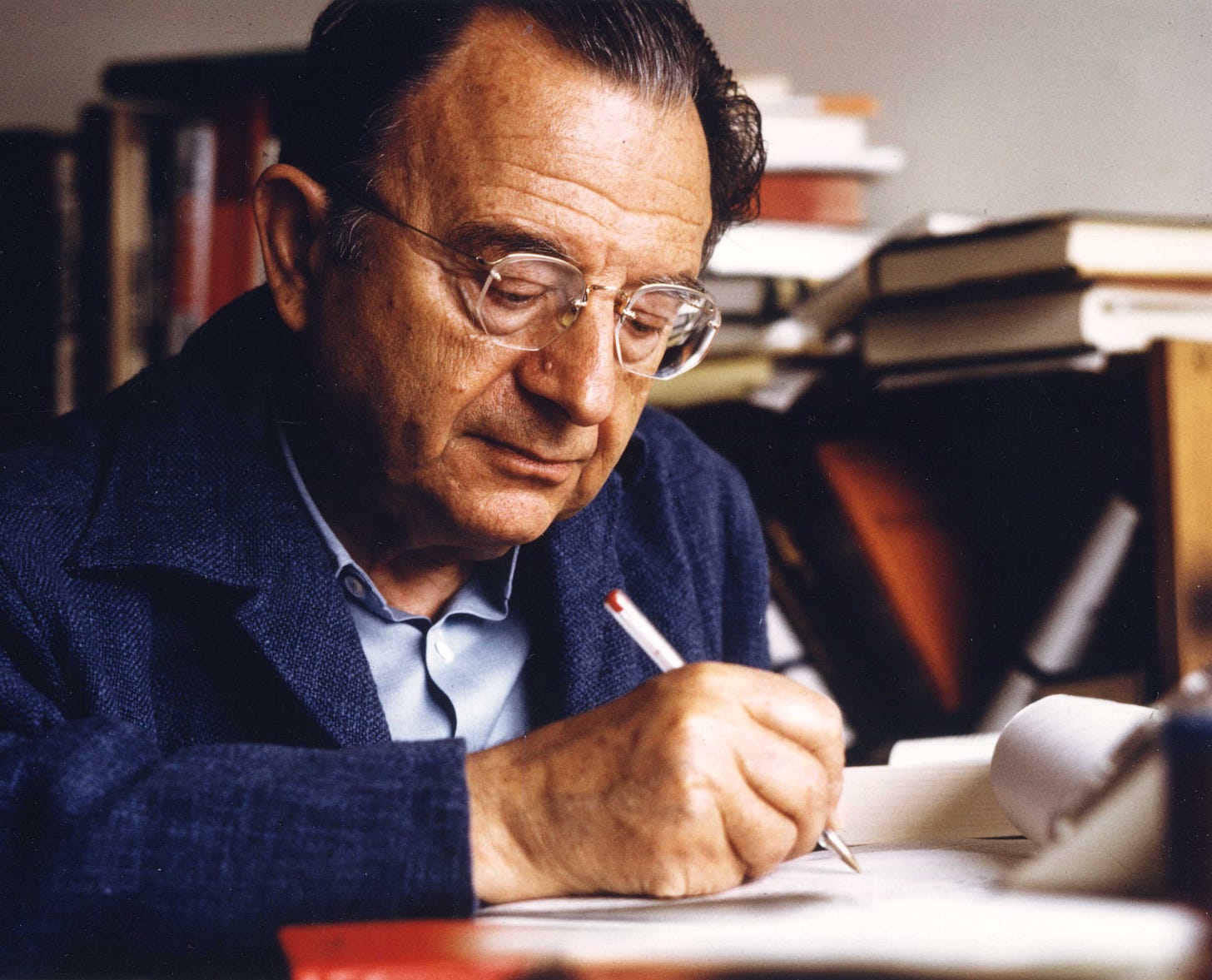

But in the work of Marxist humanists like Erich Fromm and Herbert Marcuse, and, influenced by them, in work of New Left thinkers in the late 60s,6 there was a deep distrust for the dehumanisation and subjugation of individuals, foregrounded by Leninist-Stalinist and Maoist forms of ‘collectivization’. In this, many started to stress the notion of the essential human, a focus on freedom and flourishing, and indeed, the power of, and capacity for, transformative love in societies. One of my favourite thinkers of the time is Erich Fromm:

“Marx's concept of socialism follows from his concept of man. It should be clear by now that according to this concept, socialism is not a society of regimented, automatized individuals, regardless of whether there is equality of income or not, and regardless of whether they are well-fed and well-clad. It is not a society in which the individual is subordinated to the state, to the machine, to the bureaucracy. Even if the state as an "abstract capitalist" were the employer, even if "the entire social capital were united in the hands either of a single capitalist or a single capitalist corporation," [89] this would not be socialism. In fact, as Marx says quite clearly in the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, "communism as such is not the aim of human development." What, then, is the aim?

Quite clearly the aim of socialism is man. It is to create a form of production and an organization of society in which man can overcome alienation from his product, from his work, from his fellow man, from himself and from nature; in which he can return to himself and grasp the world with his own powers, thus becoming one with the world. Socialism for Marx was, as Paul Tillich put it, "a resistance movement against the destruction of love in social reality."

He’s quoting here Paul Tillich, a socialist theologian. As I’ve said before, I’m not religious, even if I’m completely down with Jesus, and completely not down with an unfortunately very large proportion of his followers. But the overlap between Christian ethics and socialism is hardly difficult to see, unless you are the majority of Amercians, and indeed, the ‘caritas’ of charity is born of a Christian concept and formulation.7

But read that again: “A resistance movement against the destruction of love in social reality.” I know what that sounds like to me.

Sometimes that resistance may have to be about sharing food or material resources - and outside of an existing system, by private individuals getting together to do so. (Not just charities: unions, for example.) I hope that most often it is not. It is very ineffective. Much more effective would be to change our society in some more fundamental ways to ensure that this is unnecessary. Much more effective to work together to make sure that everybody has what they need. And then to work towards flourishing beyond that.

Interestingly, at this stage we come back to the flourishing that Wilde, who so hated charity as it was then, foregrounds. Wilde’s version of socialism grates on the ears of many, understandably, by its foregrounding of what he calls ‘individualism’ - the idea being that once socialism meets our basic needs, it allows us all to spend our time becoming what and who we want to be. This is very Wildean: a self-made personality, who saw living life as a sort of work of art.

Wilde’s queerness also comes through very strongly (and this essay has played a central role in gay liberation thinking for generations). He is sceptical of the (traditional) family because of its tendency to turn love into transactions and contracts, and into partnerships based on domination. This is common with many feminist thinkers, among them many Marxist feminists, and as Wilde himself points out, is also one powerful reading of Jesus’s teachings about family.8

But of course, for us to become who and what we want to be, would always be a matter of doing so together. That would be through voluntary association of course - and indeed, Wilde was also enamoured of anarchism (not the bombs part, he notes), and the notion of free associations of human beings to allow us to flourish together. We develop into who we want to be best with each other - but unshackled by the bounds of absolute need. This is what Wilde’s socialism is about, and it is very different from individualism as capitalism sees it (competition, social Darwinism, the logic of the market).

“The State is to be a voluntary association that will organise labour, and be the manufacturer and distributor of necessary commodities. The State is to make what is useful. The individual is to make what is beautiful.”

- Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man Under Socialism

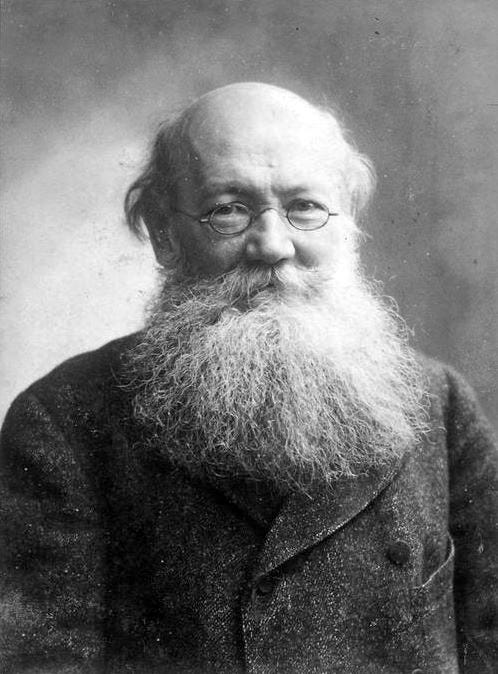

Now let’s take a step back for a minute. Does this sound familiar? Going beyond the absolute needs, and developing a flourishing of human individuals - of what is ‘beautiful’. What Wilde also calls ‘real living’ rather than ‘existence’ - by free association between people in society, unfettered by desperate hunger or homelessness. Wilde is also influenced by the work of Pyotr Kropotkin, whom he called a ‘shining white Christ’:

“It is in order to obtain for all of us joys that are now reserved to a few; in order to give leisure and the possibility of developing everyone’s intellectual capacities, that the social revolution must guarantee daily bread to all. After bread has been secured, leisure is the supreme aim.”

- Pyotr Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread

Let’s be clear: in the squint-eyed view of the Protestant work ethic common among those who live off our labour, ‘leisure’ is something derogated as a pursuit of the lazy, feckless, and morally weak. But leisure in its wider conception: what we do with our time beyond meeting our basic needs - is as important to truly fulfilling human life as any of Kropotkin or Jesus’s ‘bread’. We can choose to spend our ‘leisure’ making more money for rich people (thisn is what exloiation of labour for profit is), or to drive the general flourishing of the human and humans. In recent years, we’ve seen the further development of these ideas that we may recognise as types of ‘post-scarcity’ utopian socialism. For example, Aaron Bastani’s ‘Fully Automated Luxury Communism’ explores technological developments as ways to develop greater distribition of leisure and resources beyond ‘need’ - and recognises that capitalism as it is currently configured needs scarcity to survive.9

I do also find it interesting that charities, like some of these heterodox socialisms, could be seen to go beyond the cultural baggage of macho, puritanical, denial that you find in some versions of socialist discourse. The levelling that always used to make us seem like no-fun pariahs isn't without some element of accuracy. Queer activists often complained of Marxists that they seemed like they just couldn't stand the idea of fun. That sour-faced macho puritanism you used to see in Socialist worker meetings. If we spent more time working in community centres, we might at least feel a little glimmer of what a better world looks like.10

Beyond ‘socialism’ and beyond ‘charity’

What all this tells us is that any omodern anti-charity leftists are citing a version of charity which did precisely what the state ought to do. So many of the arguments relate only to that. They don't relate to the flourishing of civil society which, to be clear, has flourished most of all since the establishment of the welfare state. That flourishing and diversity is decreasing now, as the welfare state retracts and it becomes again replaced by food banks and homeless shelters. This is not a fundamental feature of charity practice or civil society - in a socialist society, that flourishing becomes all the more possible. But the more economic socialism retreats, the more charity picks up the slack through the existing traditions of voluntaristic almsgiving. What else is there?

The point is that charity needs socialism, but socialism also needs charity. And indeed, I see them as part of the same ethic, and the same emancipatory trajectory. This is an alternative to seeking to match move-for-move the intellectual frameworks of an increasingly unhappy society driven by capitalist realism.

I talked before about charity as an ethic: caritas, the practice of love. If we are to be clerarer about what we want from charity, it’s important we are a bit clearer about what we should think of when we say the word. That way, we won’t need to stop using it (another possibility), or constantly fight with those who want to return it to almsgiving or monastic hospitals, or those who see it as a poor substitute for socialism.

Don't think of charity as redistribution. It is not good at that. We need to stop claiming it is. We need to argue and campaign for real redistribution.

Do think of charity as practices of care in society.

Don't think of charity as meeting basic needs. But also, don't think of it as only 'nice to have'. Without social connections and mutual care we become ill, sad, and wither away. Connection and care are needs. But food, shelter and clothing should not be our job.

Do think of charity as society coming together to provide love and care in a way that binds us together. This is even more vital in the face of an industrial capitalism that degrades social relationships and makes us suspicious and judgmental of need.

Do think of charity as a way of human beings organising to care for each other and build connections.

Don't think of charity as a degrading, one-sided exchange. This is a mythology created by the people who don't want to help other people.

Don’t think of charity as a poor man’s socialism. I think it is part of socialism, but can only truly flourish when the other parts of socialism - covering basic economic need - are put into practice. In the meantime, we would be remiss not to do our best to meet those needs as best we can, when we have to.

What I want to end with is the idea that charity - even as it stands, could be a figuration of a better, socialist, future.

The Vision: Charity as advanced socialist practice

Every time we are forced to meet people’s basic needs, we’re taken away from this kind of flourishing post socialism that we would be best at. We are a terrible social substitute for full socialism and an absolutely vital driver of the kind of deep, transformed social relationships that form the end goal of socialism itself. Indeed, perhaps we are the type of socialism that can only exist fully at a later stage. Think of us as an advanced, non-authoritarian, post-scarcity socialism that is, perhaps, before its time.

If we see socialism and charity as somehow related in this way, it also means we can start to understand processes like progressive taxation, common ownership of wealth, and the production of welfare, health and social care, as part of these practices of love, care and freedom. (I guarantee that you did not expect somebody to tell you today that taxation is a practice of love, care and freedom.) What charities can teach us about is the continuing importance of voluntaristic association, of community, and of love in socialism. Of the importance of more than enough, of excess, of flourishing and burgeoning. They remind us that a socialism which doesn't recognise the value of freedom and decentralised agency and power will always be a failure of the kind of principles socialism ought to demand. Charities are a reminder that socialists don't have to be miserable. And don't have to begin and end with the state, or with material redistribution.

What I’m trying to do in these pages is to trace an alternative intellectual history of charity and civil society. I think this has been there, but until now, rarely if ever oexplored. It’s an intellectual history of charity that is queer, socialist, anarchist, and humanist, and is told from the perspective of those fighting for a more equitable society - not just working in an industry. You may ask: am I simply making an intellectual history of charity in my own image? Well, to an extent - all histories are stories shaped by the narrator. But at the very least, as I hope I demonstrated in my post about queer civil society, charity has also made me.

Am I being utopian? You bet your sweet bippy I am. What I need is a dose of capitalist realism, right? In the world of charity, or the ‘nonprofit’, I think we need to expand what Robin DG Kelley calls our 'political imaginary'. What can we dare to imagine? What do we allow ourselves to dream? Kelley, a scholar of Black emancipation, reminds us that we cannot forget to dream. And that the size of our dreams will delimit the amount of change we strive for - and achieve.

We are easily bamboozled and gaslit into believing that, for example, the very kind of social democracy we had 40 years ago, and indeed, which still exists in other places, is unimaginable. And that, within what we call the charity or nonprofit 'sector' or industry, the best we can imagine is more money from trusts and foundations, or cynical wealthy philanthropists, or some government contracts to deliver social care on the cheap. And that the ‘deep thought’ we get comes from centre-right think tanks and schools of charity 'effectiveness' selling us courses and frameworks, or justifying us (but never themselves) by our financial efficiency. Or ideas of entirely selfish 'altruism', which use the simplistic and scientifically illiterate models of neoliberalism to reduce our society, and our imaginative scope, to financial calculations.

I also want to be clear that I’m not just being sentimental - that being all too often a bedfellow of ‘charity’ both in discourse and practice. Sentiment and emotion are important - but ‘sentimentality’ uses emotion to obscure reality, not to experience, or understand it. There is much more to this than a mystical notion of universal love, or simply doing things that give us a warm glow. This is not a refutation of Marx’s materialism and a replacement of economic reality with warm fuzzies - or worst of all, with Tory paternalistic noblesse oblige and the idea that man cannot live on bread alone. (He can’t, but he also can’t live without it.)

At the same time, we might want to ask ourselves why, for both some unreconstructed Marxists and neoliberals, ‘feelings’ are so easy to laugh off and cast aside - perhaps to replaced by hardcore impact data driving utilitarian goals. What does this tell us about our dominant culture, that our emotionally-led impulses are to be resisted and mocked? I am talking about making very ‘real’ changes to the lives and living standards of actual human beings. But that includes bingo, and climbing frames, and movie clubs, and somebody telling you that you matter when you feel like you don’t. If you think we should be ‘above’ that, that’s on you. Another thing charity does well is feeling. And that is seen as its weakness. I’ll leave you to ponder that and what it says about those who make these judgments.

The cultural hegemony (that is, the dominating influence over ideas and beliefs) asserted by the establishment in the nonprofit industry (you know the people, the organisations, the institutions) is a barrier to us coming away from broken social practices. It ideologically props up and justifies an overstretched charity industry built in the mirror image of the very neoliberal economic system which is fundamentally inimical to our own purported goals.

This is all the more reason that in charitable theory and practice, we need to focus on an ethic, of freedom and care and love, the ethic of a deeply humanistic socialism. Not one degraded by its historical associations with the powerful controlling the weak. But instead, empowered by a vision of solidarity and love that makes its own practices. This change, from industry to ethic, will not come from think tanks, philanthropists, and corporate training programmes. It will only come from the people who live it, breathe it, and do it.

What does that mean practically? Well, practically it starts with this: talking. thinking and dreaming. Refusing to shut up when the latest six-figure-salaried third sector mouthpiece tells us it’s always like this, and can’t be any other way. We start by taking our view outside of an industry, to start to see what we can add - and where we overlap - with global structures and struggles against a capitalist society that sees people as profit centres. And yes, in the meantime, we can improve funding application forms, make sure we stay political and speak out against injustice, be strategic, and try not to go under or have a breakdown. I do this shit every day too - what else do you expect me to say? (I’m just tired of saying it.) The point is to think about the future you want in 50 years, not just the next financial year.

What I’m trying to do in these pages is to trace an alternative intellectual history of charity and civil society, and draw from that a different vision of charity, I’m inviting you to reclaim charity from a conservatism in discourse and ideas, from the Torygraph self-congratulations of the wealthy, and from its industrial arrangements, which fail to do justice to its potential.

We discussed in part one of this post how people have come to hate the word ‘charity’ so much (because of its negative associations) that they have started to come up with all sorts of alternatives. I want to propose a new one. How about 'socialism'? 'I work in socialism' is definitely a sentence I would find easier to say at parties.

‘Oh, that must be so rewarding, they will say.’ “Not yet,” I’ll tell them. “But it will be.”

Thanks!

Finally, a big thank you to Prof Erin Mackie for her always insightful and diligent editorial help. If anyone ever wants a good editor, get in touch and I’ll connect you.

And finally

I was talking to some colleagues this week (The Ungrateful) about whether it is time for a new generation of leaders in the charity sector. These are not going to come from infrastructure or funders. They’re going to come from people who do things. An army of bingo-callers, ping-pong table wranglers, and knackered CEOs who know their way around a blocked bog like nobody’s business. Or people burning out on fundraising for the bog brush.

Until next time….

See you in two-ish weeks for more fun and frolics. I’m going to try and track down some Paul Tillich, who is new to me.

And I might go and see the fantastic new Superman again.

No, not this w*nker.

Oh, and….

In the early 90s, Alexei Sayle, who is a bit of a comedy hero of mine, had the funniest TV sketch show I’ve ever seen to this day. It was called ‘Alexei Sayle’s Stuff.’ Check it out on YouTube. Meanwhile, we also share interests in Marxist theory...

And this one’s for Lauren Williams, who enjoyed Mr Thunderpaws last month as much as I did.

Barely Civil Society is about making the nonprofit world braver.

Here are three ways to help.

Subscribe!

Share!

Support!

If you donate, you can help me spend more time researching and writing - including some bigger projects I’m working towards. Could you buy me a coffee?

Send me a message

The messages people send me every couple of weeks are my favourite thing. Drop me a line and say hi! What made sense to you? And what didn’t? (Be nice.)

Work with me!

Check out my day job webpage.

Or don’t; see if I care.

See the report by neoloiberal extremist think tanks the Fraser Institute and the IEA. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/new-poll-finds-strong-support-socialism-uk

The extremist libertarian US Cato institute recently lost its shit about this too (2025), going straight to Stalin, Nazism and holocaust when a third of young people in America said they liked socialism. Which is totally normal, rational behaviour, obviously. And we know how much Hitler loved socialists.

https://www.cato.org/blog/young-americans-socialism-too-much-thats-problem-libertarians-must-fix

There’s a lot of work to be done on trades unions here and their overlap in terms of care, community development, and indeed the wider civil society functions in democracy. It’s interesting to consider how much charities themselves may have expanded to fill the gaps once tackled by unions, especially in post-industrial landscapes.

Clement Attlee, for example, cut his teeth and learned his socialism in Toynbee Hall and Stepney charityt Haileybury House. See https://explore.toynbeehall.org.uk/timeline/clement-attlee-at-toynbee-hall/

You can find out more about how Keynes saw this, and a general discussion of social democracy’s relation to socialism, in Clara Mattei’s ‘The Capital Order’ (2022) - Introduction.

My own view, is that it mapped pretty closely to the Communist Manifesto - a violent fantasy of domination that did far more damage, not just to the world, but to desires for a better one, than any capitalist tract.

New left thinkers were horrified by the revelations of Stalinist purges after Kruschev’s brief period of ‘thawing’, and by the bloodbaths of the Cultural Revolution in China, which led to a turn towards much more focus on individual freedom.

To be clear, I am in no way suggesting that Western Christianity has dibs on human love or charity - I’m just tracing the idea in a very Anglo-saxon tradition.

Lest we forget, Jesus wasn’t particularly big on family. He left his own, formed a new one, and cautioned: “Who is my mother? Who are my brothers?” Wilde sees this as about expanding our ideas of love and friendship beyond the bounds of bloodlines or compulsory heteroreproductive associations: very Foucauldian too.

As we see AI develop, we’re seeing precisely this battle take place, as capitalism develops systems that can remove the need for billions of office workers, and free them up to do more useful (or enjoyable) things. Instead, it will just use it to increase profits for the owners, having sucked up all the intellectual products of people’s labour for the last thousand years.

'Why are socialists always miserable f*ckers?' a friend once asked me. We’ve got a lot to be miserable about, mate. But also, I suspect some rather like it that way…. A lot like religions, keeping people miserable makes them want the ‘afterlife’ you’re selling all the more.