'Engines of social progress'? Charities, politics, and The Establishment

In most countries, the price of nonprofit status is depoliticisation. But should it be that way? Plus, Anti-trans meanies. And Pope Francis: the least worst pope ever.

Hello everyone, and welcome to the first edition of Barely Civil Society with more than 1000 subscribers. Yes, 1000 masochists assemble every two weeks to shroud-wave and hear gags and nihilism around the theme of nonprofits/ charities and philanthropy. Nobody is safe.

But seriously: thanks to all of you, especially those who have taken the time to write to me, and those who have bought a sub or a coffee. The readership is broad - from officers in small organisations to CEOs in big ones; from fundraisers to grantmakers and philanthropists; voluntary sector, businesses and public sector. A true sign of an appetite for a bit of proper challenge and debate that goes beyond the usual talking points. And some white hot memes. Also: I joke about enemies, but many of the subjects of critique are also subscribers. Most people are grown ups and they want a debate too. Often I’m saying things they know themselves all too well - but are not in a position to be able to say.

Today in BCS:

1. An exploration of charities’ right to be ‘engines of social progress’, and the Charity Commission - in light of the departure of Sir Orlando Fraser, outgoing Chair.

2. A quick look at the horrors around trans people, and finally

3. A perhaps unexpected tribute to Pope Francis.

NEXT TIME: We have an in-depth dive on trends in grantmaking that goes beyond just the standard ‘how long should our application form be?’

We’re asking: what’s being funded? Why? And how? And what is driving these changes?

Goodbye Orlando, hello ‘social progress’

Sir Orlando Fraser leaves his role as Chair of the charity commission today (25th April 2025), to be replaced in the interim by Mark Simms OBE. [For non-UK readers, see this footnote.1] Fraser has been clear that charities should not allow themselves to become involved in politics or what he calls the ‘culture wars’. And yet, many of the issues charities are set up to deal with are precisely those issues he counsels us to avoid. It’s time to look at the history, and the future, of regulating charities, and what we are allowed to say - and to think.

When Fraser took over, the search for a Chair was called ‘shambolic’ and took a year.2 In 2021, Martin Thomas was chosen by Boris Johnson superfan Nadine Dorries. Alas, he resigned a week later, when it transpired he had been removed from a previous role as a charity chair after sending a picture of himself in a branch of Victoria’s Secret to a female employee.3 Perhaps he was asking for advice while he tried on a basque?4

The appointment committee declined to re-run the process, and instead, in 2022, Orlando, already a long-serving member of the board, was appointed. The DCMS panel refused to endorse his appointment - not, they said, because of the candidate himself, but because of the sheer paucity of the shortlist. They decried ‘a lack of care, and attention’ by the panel, leading to an ‘archetypical and unimaginative’ choice.5

But Nadine was convinced. Perhaps there was something about the name: ‘Orlando,’ she likely swooned. He sounded like a shining white medieval knight on a fiery steed, and he was indeed white, quite literally a Knight, and some of his ideas about charity did seem to come from the 13th century.

A lawyer and Queen’s Council, the son of an Earl’s daughter and a Tory grandee, married to Winston Churchill’s great granddaughter, Clementine Hambro, he had even stood as a Conservative candidate in 2005.6 He was a member of the right wing social policy think-tank Centre for Social Justice (also known around here as the Centre for Victorian Justice), which was set up by Iain Duncan’ Donuts to provide a moral figleaf for Tory austerity and workfare.

7 NCVO expressed ‘disappointment’ at a lack of political independence, and Labour said they had ignored due process just to get a Tory on b/Board.

“The chair of the Charity Commission is an important post, and the public must have confidence that this role is independent, not party political, and that there is no conflict of interest in investigations the Commission carries out. Instead, this is another case of the Tories looking after their own.” - Lucy Powell, MP8

So, how did it go?

Some may be surprised to hear me say I think his reign was slightly less overtly antipathetic to charities, compared with previous regimes. Which, perhaps, is not really saying much. He oversaw the much deserved smashing of the Captain Tom charity, and oversaw a sticky challenge to Mermaids, the trans children and youth charity (a whole essay in itself). But he did quite regularly use the platform to warn against charities getting involved in the ‘culture wars’. That, indeed, was why he was appointed. The problem, of course, is that such ‘culture wars’ are often at the very centre of the changes charities want (and are funded to fight for) in society.

Fraser said in his valedictory interview for the Times recently that “the important thing is for charities to stick to their ‘core objectives” […] “If a charity decides it’s not so much a charity but an engine for social progress, we can step in.” But in that, some of us may have felt the core conflict was laid bare. For some of us, charities are engines for social progress, and indeed, should be. They are especially so because they are supposed to be an active part of civil society: that world of discourse, discussion, debate, independent and voluntary action, which is vital to a flourishing democracy, because it does indeed drive social change and progress.

“Charities would do best to avoid being distracted by the culture wars, calm down and focus on sticking to their core purposes. […] If a charity decides it’s not so much a charity but an engine for social progress, we can step in.”

- Orlando Fraser, The Times, 11th April 2025

How we got there

This had been brewing a long time. The Tories had been particularly looking for someone who would wade in on culture wars issues, while arguing, of course, that that they were trying to eradicate or end them. (This is much like Russia claiming it is trying to end war in Ukraine - by winning it.)

The ‘charity gagging bill’ of 2013 left charities afraid to speak out on politics.9 The new law saddled trustees with strict legal obligations they have to abide by around campaigning or lobbying, meaning many became nervous about doing or saying anything that might have legal ramifications. Meanwhile, private sector lobbying was left entirely alone – only those who might speak out against the establishment were affected. Owen Jones points in his book The Establishment, to which we will return throughout the rest of this piece, that while this was a Tory initiative, Ed Miliband had also criticised unions – he sees it as a broader strategy that spans the political establishment, protecting their shared interests.10 Just in advance of the bill in 2014, the whole Board of the Charity Commission was replaced by Francis Maude and William Shawcross – supposedly to modernise it, although only one of the appointees had any knowledge of the charity sector.11

By 2020, calls for the depoliticisation of charities had reached fever pitch. The Good Law Project warned that the Tories were trying to appoint one of their own – and of course, they were absolutely right.12 As many looked over the Atlantic to the Black Lives Matter movement, some charities – particularly cultural ones – began to look more closely at their links to slavery and colonialism. (Perhaps because it’s easier to talk about statues and slavery than to ask whether anyone can afford to join the National Trust.) And the Common Sense group were among those outraged by things like the National Trust’s sudden discovery of slavery and gay people. That same year, the ‘Common Sense’ group of Tory MPs and peers – “formed to speak for the silent majority of voters tired of being patronised by elitist bourgeois liberals whenever issues such as immigration or law and order are raised”.13 In a letter to the Torygraph, they asserted that “Part of our mission is to ensure that institutional custodians of history and heritage, tasked with safeguarding and celebrating British values, are not coloured by cultural Marxist dogma, colloquially known as the ‘woke agenda’.”

The complaints piled up: UNICEF stepping in to feed starving British children during the COVID pandemic was described by Jacob Rees-Mogg in 2020 as a “political stunt.”14 Barnardo’s was reported to the Charity Commission for daring to mention in a blog that BAME people faced additional challenges.15 Oliver Dowden (then Culture Secretary) said there was “a worrying trend in some charities that appear to have been hijacked by a vocal minority seeking to burnish their woke credentials.” By 2021, Dowden was having a wobbler about the National Trust seeming to besmirch Winston Churchill’s name, or about Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity moving the statue of Thomas Guy from the forecourt over his shares in the South Sea Company. Dowden’s take was:

“This is just another example of a worrying trend in some charities that appear to have been hijacked by a vocal minority seeking to burnish their woke credentials. In so doing they not only distract charities from their core missions but also waste large amounts of time and money. I’m quite sure this is not what the millions of British people who donate to charities every year had intended their hard-earned and thoughtfully donated cash to be spent on.”16

But statues are, after all, quite literally just totems. This was about something much bigger. One thing I can’t help thinking is that all the focus on ‘woke’ and identity politics in charities was a welcome distraction for a government who had deliberately impoverished and immiserated a large swath of their electorate over 10 nasty years. They got some pretty sharp clap back when they started on child poverty charities - so, much better to stick to trans people and migrants.

Barely civil society: are charities allowed to think?

Interestingly, in between the demands that charities should not be crusading in the culture wars, Fraser and the Commission have repeatedly defended the role of think-tanks which push very strong political agendas. This is hardly surprising since, as we saw earlier, the Charity Commission has long had deep links with right-wing think-tanks often described as charities. It was also noted in 2013 that other several members of the Charity Commission’s spanking new Board had worked with think tanks who had attempted to stop charities campaigning.

As Owen Jones notes, think tanks are intellectual ‘outriders’, who do the work of making sure that when people in power are looking around for ideas, there are ‘the right ones’ waiting for them to pick up. Appropriately for the discussion here, he’s referencing Milton Friedman’s famous (and accurate) dictum that the “basic function” of policy thinkers is “to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.”17

2013 alumnus-member of the Commission’s board, Gwythian Prins, had been associated with the radical free market think tank Institute for Economic Affairs, the ideological promulgator of Friedman and Hayek’s neoliberalism, the progenitor and outrider of Thatcher and Reagan’s extremist economics (which, by comparison with today, seem almost tame), favourite of noted intellectual heavyweight Liz Truss, and one of the most vocal about removing charities’ right to campaign. The IEA had written a report in 2012 where it called charities ‘sockpuppets’ campaigning for Government policies on behalf of the Government itself.

This was a particularly nasty report, arguing that charities ‘funded by the government’ equate to a government funding “the lobbying of itself”, which “is subverting democracy and debasing the concept of charity. It is also an unnecessary and wasteful use of taxpayers’ money. By skewing the public debate and political process in this way, genuine civil society is being cold-shouldered.”18

Note that phrase: ‘genuine civil society’. There is a strong current of thought amongst right wingers that charities are not ‘genuine’ civil society. For them, this is why it is acceptable to muzzle charities: because they are not ‘genuine’ civil society - worse, rather than being contributors to democracy, they are a threat to it. That’s pretty rich coming from the IEA.

But it should surely work both ways then? Most think tanks are registered charities, as indeed the IEA is. So how is it allowed to campaign and influence, when ‘charities’ (ie. not think tanks) are not? When, in 2024, The Good Law Project brought a legal challenge against the IEA’s charitable status, fresh from the latter’s leading role in Liz Truss’s budget shitshow, Fraser and the Commission immediately declined to investigate, and mounted an impassioned defence of the think tank’s key role in democracy.

“Think tanks are critical to our political ecosystem. Their work is valued by parliamentarians and those interested in public policy. Their model of policy development and scrutiny is present in most established democratic nations, where solutions to the toughest challenges are researched, analysed and debated with gusto. Some argue that think tanks are inherently political organisations and, accordingly, don’t deserve the benefits that charitable status brings. I disagree. Charitable think tanks make an enormously positive contribution to intellectual debate. That is a good thing, whatever intellectual tradition they come from.”

- Orlando Fraser, ‘Yes, political think tanks deserve their charitable status’, 14th March 2024.19

Now, this is a rousing defence, essentially, of civil society. And yet, for Fraser and the CC, while the think tanks’ intellectual contributions to politics are to be welcomed, charities should not, because they are, wait for it, barely civil society at all.

Now, it wouldn’t be much of a stretch to point out that general ‘charities’ as we would more widely understand them tend to work in the name of people who get a raw deal in our society, and have considerably less power than others. And I have a sense that the IEA know that full well: reading between the lines, isn’t this exactly what they are saying here?

“State-funded charities and NGOs usually campaign for causes which do not enjoy widespread support amongst the general public (e.g. foreign aid, temperance,20 identity politics). They typically lobby for bigger government, higher taxes, greater regulation and the creation of new agencies to oversee and enforce new laws. In many cases, they call for increased funding for themselves and their associated departments.”21

At the end of the day, there is a vast weighting of think tanks towards right-wing causes, including, of course, the Centre for Social Justice, the IEA, the Cato Institute, Henry Jackson, the Heritage Foundation, and any number of other free-market radical and conservative think tanks which make up by far the majority of the think-tank sphere in the UK (and even more so in the US - transatlantic branches are common). This is largely because the major donors, wealthy philanthropists and captains of industry who tend to fund such organisations tend to be fonder of right wing economic causes than left, for obvious reasons.22

Charities also, of course, have a habit of meeting real people - most of whom will be badly done to by the prevailing ideologies, policies, and socio-economic structures of our current society. That is very dangerous: those are voices the powerful and wealthy do not want to hear. It’s no surprise that anyone who raises those would be asked to stay silent on politics, while the input of predominantly right-wing, neoliberal think tanks would be welcomed. Telling charities to ‘stick to your knitting’ and to let the grown-ups of ‘genuine civil society’ do the thinking. All of this helps to ensure that the ideas lying around - dangerously waiting for a crisis when someone might pick them up - aren’t those that might challenge the wealthy and powerful. What Orlando and the think-tank mafia are telling us is that, as Orlando puts it, charities should not become “engines of social progress” - because it is the wrong kind of social progress.

The Establishment

To be clear, this is not an ad hominem critique of Orlando Fraser, or indeed, his background, identity, or even his individual political proclivities. The point here is that what he represents - and what the Charity Commission in its current and historical role represents - is the establishment. Jones describes this as

“made up – as it has always been – of powerful groups that need to protect their position in a democracy in which almost the entire adult population has the right to vote. The establishment represents an attempt on behalf of these groups to "manage" democracy, to make sure that it does not threaten their own interests. In this respect, it might be seen as a firewall that insulates them from the wider population. As the well-connected rightwing blogger and columnist Paul Staines puts it approvingly: "We've had nearly a century of universal suffrage now, and what happens is capital finds ways to protect itself from, you know, the voters.”’

Outside of the nastier right wing dogma to which he has at least provided a less overtly aggressive face, Orlando’s approach has just been deeply conservative - small C - with all the baggage you would expect. He hails noblesse oblige, loves the royal family and all they do for charities. “His wife, Clemmie, was a five-year-old bridesmaid at Prince Charles and Diana’s wedding”)23 Meanwhile, Orlando also tells us of his belief in the greatness of the super rich and their giving, as a purely voluntaristic principle, and one for which we should be deeply grateful: “We need to celebrate philanthropists instead of hounding or shaming them. Give them a small gong or an invitation to meet a royal.” (Times)

So alongside the frothing radicalism of the neoliberal vanguard, there is also a sense of trying to conserve, preserve, and continue the hegemony (dominating influence) of the ruling class culturally speaking, especially in a period of rampant Toryism. This confluence of the two types of conservatism has been central to the Conservative party itself for fifty years now. With that said, Labour has never been a stranger to the Establishment. The desire to maintain, at root, the status quo is something that both main parties have long had in common.

The Charity Commission and its forebears have always been a central part of the establishment; about trying to preserve the power of the powerful; about preventing charities becoming ‘engines of social progress’, going back far beyond the previous Government’s special focus.

Regulating power

The ‘regulation’ of charities throughout our history has always been very much about ideology, and the bounds of acceptable questions of state and power; about what is virtuous; about who or what cause is ‘deserving’; and about what responsibility for care we have towards each other in our society. And of course, the power of the state and the people - especially those people it has to control or cast aside. In this process, the ongoing themes have been about protecting the money of the wealthy, maintaining the authority and legitimacy of the state, and limiting the scope of what the people are allowed to demand.

Those strands have been in constant development, with different levels of focus at each point: early on, the English Reformation saw a movement of charity from the church to the state, which continued throughout the Elizabethan poor laws. Even then, sedition was a key concern - to what extent might charities undermine the power of the monarch, especially given their close contact with the poor and disaffected? As the mercantile classes rose, and with the rise of private wealth, focuses shifted increasingly to protecting the use of the money of the wealthy. As parliamentary democracy developed, we saw a later flourishing of civil society and the growth of the public sphere in the Enlightenment, during which charity strengthened, and became more organised, while civil society organisations designed to campaign and influence politics grew alongside more organised charity and welfare programmes. By the 19th century, reforms of charity again focused on protecting the money of the wealthy and on accountability - but campaigning often sat alongside charitable activity - for example in temperance, or birth control movements. In the late 19th century and early twentieth century, with the rise of the oligarchs and fabulously wealthy industrialists, charity was used as an alternative, and a bolster against, the growing social dissent and the formation of unions, and indeed, various rabbles and revolts threatening industrialised capitalism.

At each stage, developing ‘regulation’ by the Charity Commission and its antecedents has been a significant part of ensuring that charities do not become those feared ‘engines of social progress’. Ensuring that charities cannot develop a power and a politics of their own has been vital - because, one can only assume, the threat is real. Much as Henry VIII no doubt recognised when he dissolved the monasteries, the connection of the people to a different power base through the spiritual as well as financial practice of almsgiving, or latterly for other monarchs and Governments, or oligarchs, the urgent need has been to ensure that charities do not try to think beyond the aims and objectives of the wealthy and powerful. The Charity Commission, as representative of the establishment, has always, but perhaps most explicitly in the last 10 or so years, become a way of ensuring that the wrong people don’t have the right to think. And keeping the Commission stuffed with members of the establishment is a key part of that, and always has been.

Alongside this, the need to constantly parade the failings of charities, as the Commission has increasingly done over the last few years, undermining trust (but dressed up in remarkable Orwellian doublespeak as ‘preserving trust’ for the public) is again all part of controlling dissent in civil society, and deciding who is allowed to be part of it. And charities are a lot easier to regulate than universities, with their massive resources, and of course a strong tradition of freedom of thought. But as we have seen in the UK, and even more so in the US, they are not safe either.

If all this seems bleak or disempowering, I want to point something out: there is an upside to this. The perceived need for this level of control and scrutiny is a sign that there is real power to be had. And that the potential in this sector is much greater than the establishment would like us to believe.

One of the assertions I find most glib and patently untrue in the IEA attack article on charities is the claim that charities tend to lobby for ‘causes which do not enjoy widespread support amongst the general public […]. They typically lobby for bigger government, higher taxes, greater regulation.’ Well I don’t think Barnardo’s is an unpopular cause, do you? Food banks and food poverty are things the public consistently objects to, as we saw in the outpouring of support for Marcus Rashford’s campaign. And the public have long shown a preference for higher, not lower taxes.24 The public certainly was not against greater regulation after the (last) financial crash - just before all this piling in on charities started to happen.25

In fact, I would suggest that what this whole strand of history, and the culture wars rhetoric of the last ten years really shows, is that charities are arguing for what a sizeable portion of the population actually want. How very, very troubling this thought must be - and how necessary that it is silenced whenever it appears.

“We live in a time of Establishment triumphalism, when other ways of running society are portrayed as unthinkable. That triumphalism must be chipped away if we are to build a different sort of society.”

- Owen Jones, The Establishment, pp xviii - xix.

A proud engine of social progress

If there is a conclusion to be drawn here, for me it is this. We need to find some way of depoliticising the charity commission. But we need to find a way of repoliticising charities. That does not mean necessarily turning them into outright party political campaigners - there may need to remain limits. But the deliberate attempts to separate charities from civil society have to stop. Civil society makes much more sense when it is driven by real lives - I would particularly like to see more campaigning from charities who are actively delivering support. The less afraid charities are of speaking out, the more smaller charities in their communities day in day out will be able to make arguments without fear of legal consequences their trustees will fear.

At the same time, there is a reality that the more money we accept from the state, or from the wealthy, and indeed, from the establishment, the less we will be able to challenge the hegemony. Current think tanks on the left, especially when focused on charities, are so bound up in trying to gain approval within the very narrow Overton window allowed that they barely say anything beyond ‘please be kinder to charity workers’, or, most often, ‘charities save the state a lot of money, you know’ or ‘we have to get more efficient so we can deliver government contracts better’. We have to go beyond this.

At the very least, lawfare attempts to regulate us into silence should be beyond the pale, and part of a covenant with the state which has been fundamentally undermined over the last 15 years, perhaps more than in any time in the last two centuries. Charities have to return to their central role in civil society. They have every bit as much authority - particularly of the moral variety - as any think tank.

And finally, if the price for your charitable status is silence, do you want to be a charity? Because there are other options.

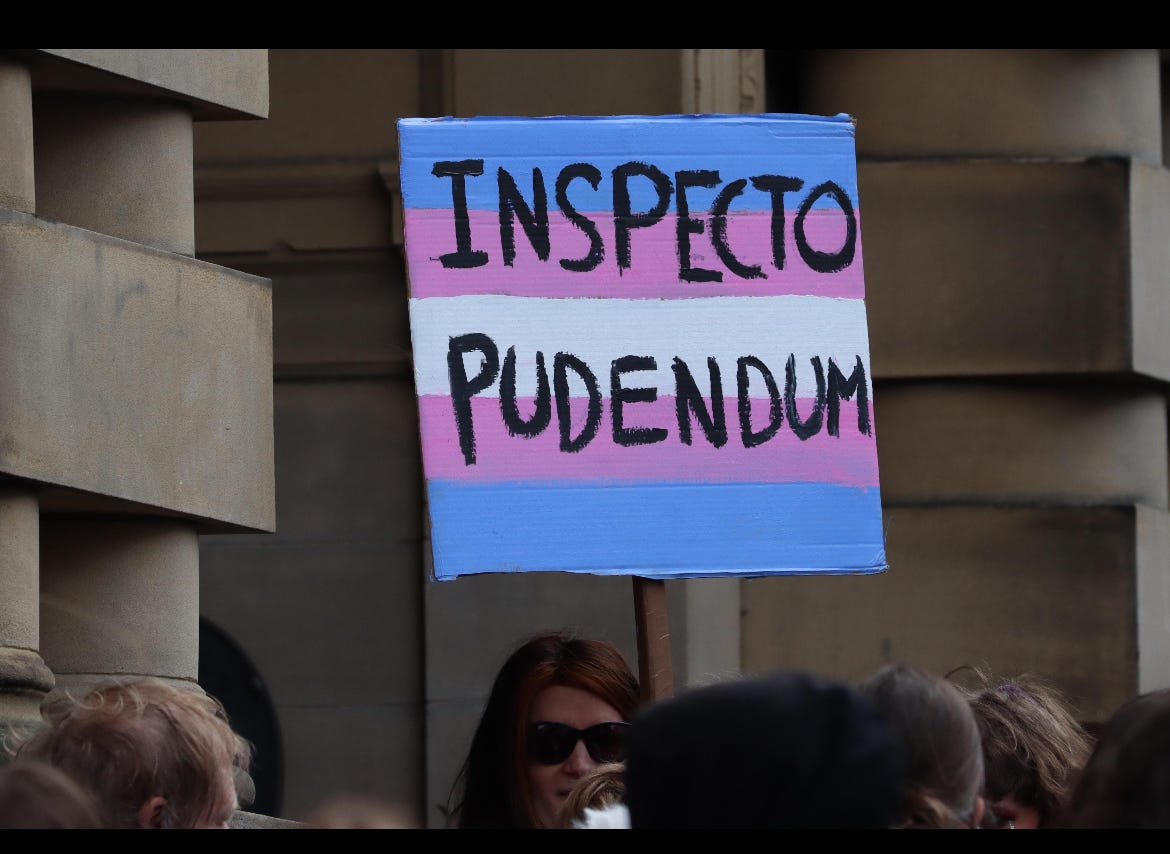

Trans horrors: here we go again.

The trans thing this week was utterly appalling. I just imagined how I would feel walking into a bathroom or a changing room tomorrow as a trans person. What do they call that again? Oh yes. EMPATHY.

And for myself, I felt a deep anxiety in the pit of my stomach which was really just a rush back to the horrors of the eighties and nineties as queer people got pilloried daily by the press and the state - and of course, by the public. A matter of a year ago me and my husband were sobbing our way through Heartstopper and marvelling at how much the world had changed.

It’s not so much anxiety just for the content of the judgment itself - we can argue about that, and to be honest, arguing about questions like ‘what is the legal definition of a woman’ has been one of the biggest problems. It’s the sheer nastiness of the celebrating and political point scoring. The fact that instantly toilets are at the top of the agenda again says a lot about how infantile our obsessions with sex and gender are. The primal scene of toilet training, the development of gendered identity catalysed by shame, fear of invasion, all hanging around like a bad smell in a public bog. Kemi Badenoch has been instantly in there thrashing about and daubing it all over the walls with a toilet brush of course.

And it’s no surprise to me at least that the testing point of this comes from Scotland again - unfortunately a source of the nastiest last gasps of legal challenge to antigay legislation in the late 90s and early 00s, and of course a late adopter on ‘homosexual’ law reform. Alongside the egalitarian culture there is also a deep social conservatism largely based around the puritanical churches. This balance is always one that threatens to upset the SNP. It also reminded me of queer and sex positive battles with some more puritanical American feminists in the 90s, where it was amazing how a few rapidly found common cause with right wing conservatives.

As for Labour and Keir Starmer’s gaslighting and Polyannaish political response, all I can say is, the only ‘clarity’ here is just how much he wants a trade deal with JD Vance. Not for the first time, Starmer is discovering that often, just by waiting, the moment and opportunity he needs will appear. By the end of the year I fear we can also look forward to large groups of nutters harassing women outside abortion clinics. Not to mention chlorinated chicken.

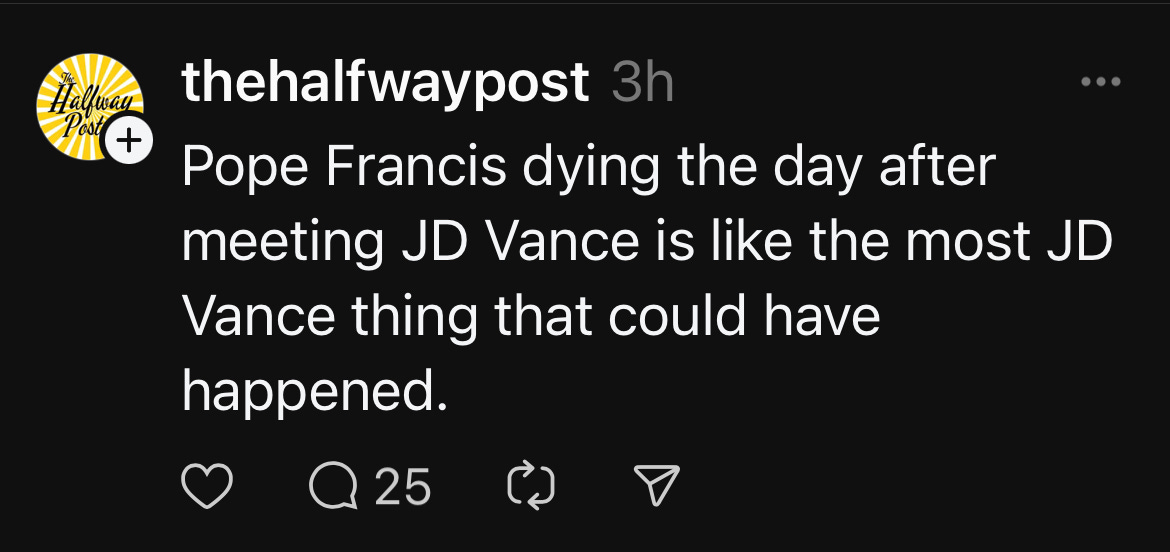

The Pope

I’m far from religious, but I am sad that we have lost this guy, and anxious about what is to come now. Believe me, I’m well aware of all the negatives. But especially in the current climate, it matters to me, and others, that he said things like this:

“Giving more importance to the adjective [gay] rather than the noun [man], this is not good. We are all human beings and have dignity. It does not matter who you are, or how you live your life – you do not lose your dignity.

“There are people that prefer to select or discard people because of the adjective. These people don’t have a human heart.”

https://www.newwaysministry.org/2019/04/19/pope-francis-comments-to-uk-comedian-stress-the-human-dignity-of-gay-people/

We disagreed on plenty, some of it very serious. But this was a man who seemed to care about human beings more than most in his line of work. Definitely the least worst pope ever.

No wonder meeting that piece of shit Vance killed him.

Barely Civil Society is trying to create deeper debate in the UK charity sector.

Here are three ways to help BCS make charity braver.

1. Subscribe

Barely Civil Society is a reader-supported publication. Please think about buying a coffee or even getting a paid subscription. It’s about a quid a week, for as many words as you get with most magazines. Or just send this on to your friends or mortal enemies.

2. Share

It is not as scary to share ideas in the sector as people make out. Help spread the word!

OR….

And finally…

Let’s work together! As a consultant, I work with a wide range of charities and grantmaking organisations to help them do what they do better. That ranges from research and learning partnerships, to strategy development and income generation.

And don’t worry: like most charities, I become very tame if you pay me.

And of course, the money I make from my day job pays for my research and campaigning on the voluntary sector. Like most think tanks.

If you’re not based in the UK, some of this will be boring or confusing or both. But the general questions about regulating charities and their political affiliations may still be of some interest. The Charity Commission is the official regulator of charities in England and Wales. It oversees how charities are run, ensures they follow the law, and decides who can and can’t register as a charity. Over the last 15 years it’s become increasingly associated with the UK Conservative Government, and deciding who can or cannot make statements perceived to be political. Like the US, tax statuses are key, but in general, regulation is thought to be stricter. So the appointment of a Chair is important, and tells us a lot about how charities are perceived - and how much difference they are allowed to make.

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/jan/11/shambles-mps-attack-appointment-of-charity-commission-chair

This was in a previous role as Chair at…. wait for it…. Women for Women, a charity for women survivors of war.

Sadly no, it was the usual, and there were other bullying allegations, all of which is pretty much standard for men who reach these levels of power, because patriarchy. See ‘New chair of charities watchdog resigns over ‘inappropriate’ behaviour,’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/dec/17/new-chair-of-charities-watchdog-resigns-week-after-his-appointment-to-role

https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/378/digital-culture-media-and-sport-committee/news/165221/committee-do-not-formally-endorse-choice-of-charity-commission-chair/

https://www.thetimes.com/uk/society/article/charities-should-avoid-culture-wars-and-stick-to-their-core-aims-q8b7qf6t3?utm

This is from a really excellent investigation by Kirsty Weakley, ‘Who is really in charge at the Charity Commission?’, Charity Finance, 26th April 2016. https://www.civilsociety.co.uk/finance/who-is-really-in-charge-at-the-charity-commission-.html

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/mar/09/tories-criticised-for-choosing-ex-party-candidate-to-chair-charity-commission

Actually the Transparency of Lobbying, Non-Party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act 2014. Among other things, this restricted political campaigning by charities and non-party organisations in the 12 months before a general election, and broadened the definition of regulated campaigning to include anything that could be “reasonably regarded as intended to promote or procure electoral success” for a party or candidate – even if the charity or organisation did not name them explicitly.

Owen Jones, The Establishment, 2014, pp80-81

https://www.civilsociety.co.uk/finance/who-is-really-in-charge-at-the-charity-commission-.html

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/sep/17/legal-challenge-launched-over-anti-woke-agenda-of-charity-commission

They were particularly exercised by the NT’s willingness to link Churchill’s family home with slavery and colonialism. Good job they didn’t mention the whole antisemite drunk woman-hater thing. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/opinion/2020/11/09/letterswill-police-break-armistice-day-ceremonies-wednesday/

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/dec/17/jacob-rees-mogg-faces-backlash-over-unicef-schools-food-aid-attack

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/05/barnardos-hits-back-at-tory-mps-upset-by-talk-of-white-privilege

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/culture-secretary-oliver-dowden-op-ed-on-appointment-of-new-charity-commission-chair

Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom, 1982, pp xiii-xiv.

Christopher Snowdon, ‘Sock Puppets: How the government lobbies itself and why.’ 11 June, 2012. https://iea.org.uk/publications/research/sock-puppets-how-the-government-lobbies-itself-and-why

https://charitycommission.blog.gov.uk/2024/03/14/yes-political-think-tanks-deserve-their-charitable-status/

Temperance????

I think it’s interesting here that they specify charities with any state funding - which is a lot of them. But I suspect that also largely describes charities who actually deliver help and support (because the Government, local or national, contracts them). There’s something about the fact that those charities will have actual contact with the ‘poor and needy’, which means they will no doubt tend to speak up for those people.

Owen Jones notes that left wing think tanks tend to sprout up briefly and disappear. Those that do survive - he mentions IPPR, but the main charity one is pretty similar - tend to be rather ‘technocratic’ outfits who just argue for piecemeal reform on policy issues. They could be best described as dead centre rather than any kind of left, I think.

The Chair of Harry’s charity might disagree. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c8e7z2e4pkno

https://natcen.ac.uk/public-support-higher-taxes-remains-steady-whilst-dissatisfaction-nhs-grows

Not to flatten this issue here: there are plenty of charities who support very unpopular causes. But it’s too convenient to suggest that all charities are just a lunatic fringe - unlike the IEA.

Nb another great article - thank you

Interested in how you see CICs, and whether you think they are a way around the 'charity' issues?