Goodbye NCS. It’s been… weird.

What next for young people? Reflecting on the last of the Big Society Boondoggles, and a future for youth work. Plus latest charity sh*tshow updates.

Boondoggle, baby, yeah.

One of my favourite words is ‘boondoggle’.

It does sound like something Austin Powers would say, but the Cambridge dictionary defines it as “an unnecessary and expensive piece of work, especially one that is paid for by the public.” There’s more. It’s usually continued due to political motivations which have nothing to do with the project itself, or the benefits it may provide. Often they are continued simply because you would lose too much face to just stick a fork in it and cut your losses.

New governments are always full of them. The Big Society Bonanza in the voluntary and public sector that followed the election of the ConDem coalition was a particularly fruitful time for them. This was just as huge cuts to public services, with a massive impact on the voluntary sector, started to decimate provision in all sorts of areas.

But the last of the Big Society boondoggles—National Citizen Service—has expired. I should start by saying I have sympathy for the people who will be losing their jobs, and it’s important we recognise that a lot of young people had a really great time, and probably will cherish the experience for the rest of their lives. I liked the idea of trying to bring together young people from different backgrounds - even if I fear that didn’t work as people thought it did.

But beyond that, the phrase “The government believes that a new approach is needed to support young people with the challenges of today,” was an understatement of epic proportions.

As Big Society boondoggles go, NCS was one of the biggest. Up until 2019, it was allocated £1.5bn (yes, billion) of Government money. Most recently it has only (only) had about £50m a year. Even in the early days of NCS, more than 600 youth centres closed and nearly 139,000 youth service places were lost between 2012 and 2016—while 95% of the Government’s budget for youth services was spent on NCS from 2014-18.

NCS - A Perfect Solution for a Different Problem

For me, and many others, NCS never seemed like a solution to the challenges for young people of today, even when it first appeared. I met some of the architects of the scheme—they were sincere and decent and really believed in what they were doing. I have the greatest respect for them; I just never agreed that it was the right solution, and nor indeed did most in the youth sector. Not enough questions were raised at the time, for the same reason most of the Big Society changes were not resisted—because people were glad that anything at all remained. And to badmouth it was to risk being left behind.

As I’ll argue, the problem was always that NCS took money, resources, and attention away from day-in, day-out youth work in communities, and from targeted youth services. These two vital tentpoles of how youth work is meant to ‘work’ were overwritten all at once by this strange confection which sometimes seemed designed to please the Daily Mail and Express, and persuade their voter base of the return of National Service, all with faint whiffs of Enid Blyton and the Little Rascals.

But the problem it claimed to solve was very much one that was framed by adult perceptions of young people and their deficits, rather than any lived experiences of young people themselves, or any expertise of those who knew what challenges those young people - and those who cared for them - actually faced. The underlying cultural significations in essence always felt like the same old ones conservative cultures project onto young people: that young people need to feel (more correctly, I think, to act) like part of their community and society, respect their elders, give something back and not be so selfish, and have some markers in their lives on the road to adulthood which would make them ‘grow up.’

The point is that fundamentally, NCS’s change of focus for youth work was ideological, and based on an idea of the world people wanted to live in - not the real world anyone actually inhabited. Clearly, there was a huge amount of nostalgia involved. I’m all for young people feeling like part of their community and society, but I think there’s a lot of work that the community and society need to do to make that happen for many young people who have been ‘left behind’. I’m all for young people feeling like they can contribute to society, but that’s not what ‘giving something back’ is. Many have had nothing. And it is beyond irony that this was announced just before young people ransacked the Costa under my flat in Camden, and burned down the youth centre containing all our multimedia equipment (that we used to work with the very same young people….). It felt unlikely that a few weeks of boondoggling was going to solve the problems of Britain’s youth.

NCS Replaced Youth Work

The biggest problem with NCS was exactly what it took away. Much as I’m sure there is a great deal of rethinking that could be done for youth work, there are some things we already know are absolutely vital, and essentially, NCS took out the two key tentpoles that make youth work effective: universal youth work and targeted youth work.

Universal youth work works best when it’s embedded in communities, delivered day-in, day-out by workers that young people get to know. It thrives on trusted adults and strong groups of young people who can bond with each other, in safe spaces that feel lasting, familiar, and present. It’s important because many young people have never had the chance to build secure attachments. This is their chance to do so with peers and grown ups, which many have simply never had the chance to do before. This kind of youth work isn’t just about dealing with problems; it also creates quality of life and opportunity for young people in a local area. It works because of those lasting relationships—relationships built over time, with a clear presence, familiar faces. People a deep knowledge of the area, not to mention links to the wider community. Universal youth work is the absolute baseline, and without it, very little else can happen effectively. The biggest strength of universal youth work, and its critical success factor, is that it’s there for the long haul.

But it’s not enough on its own. You also need targeted youth work, which focuses on young people with particular needs. This includes alternative education for those excluded from school, and specialist work for specific groups: LGBT youth, young people with disabilities, young people in or leaving care, kids with mental health problems (which now feels like all kids), and those starting to get involved in crime - youth offending teams and outreach services are absolutely vital, and should not just be police-lite.

Now targeted work happens much better when it’s combined with universal youth work, because there’s already a solid baseline to work from. And most other forms of youth work—mentoring, counselling, volunteering—work best when universal and targeted youth work exist together, hand in hand.

But NCS curtailed both of these things through its voracious funding. It took away presence, longevity, and a truly place-based approach from universal youth work. What was left might have been “universal” in the sense that it was undifferentiated, but it didn’t do the important things universal youth work is meant to do. It certainly didn’t deliver the stuff that works best for young people who need the greatest support.

And it didn’t just hollow out universal youth work, either. It also lessened opportunities for targeted work. Gone was a truly differentiated youth work that could take account of young people’s individual needs—or the needs of specific groups with their own challenges, shaped by any number of factors: vulnerabilities, risks, even just interests (note just how many NCS programmes were delivered by sports organisations). Instead, we got an expensive, short-term, so-called “universal” intervention, which didn’t do the job that universal work is meant to do, and removed most of the chance for targeted work too.

NCS overwrote the two most vital models of youth work and replaced them with a third that was just ‘nice to have’.

From youth to violence

This was not without consequences. A whole range of youth-focused problems — none of them new, but all of them unchecked. Not just riots, but over time, the rise and rise of serious youth violence.

The youth violence strategy that appeared had some things to recommend it, but it was largely undeliverable. The public health approach to youth violence, looking at data, analysing risk factors, identifying preventative measures, taking young people’s violence as a matter of holistic life-world and shaped by issues like adverse childhood experiences, were all well and good, but how do you engage with that when the infrastructure for youth work had been torn down?

Instead, all that was left were things like talking to young people in hospital after they’d been stabbed (and hats off to Red Thread for their excellent work). Or workshops to teach conflict de-escalation (LEAP, also brilliant). But these efforts had to be so narrowly targeted because they were all that could be left without the broader context. Just looking for young people who were in danger of a particular kind of violence replaced any kind of real, broader strategy. And because the place-based, ongoing youth work had been stripped away, there was no foundation for these interventions to sit within.

Young people became, at best, sites for intervention. The other thing you might notice about this is how dehumanising a violence-first approach is. Young people end up reduced to potential criminal acts. The knife crime agenda replaced the youth agenda.

Again, none of this is to blame those who created and ran NCS. But it’s clear that NCS was used as a key part of a broader strategy that has led to the wholesale failure of our support for young people in the UK. And as for the money that was thrown at NCS—all that could have made a real difference in local, disadvantaged communities over many years.

At the end of the day, I don’t really have a problem with NCS as a programme - it was a nice thing. Many of the older among us will remember fondly summer schools run by Local Authorities in years past. I have a problem with its political, social, and economic impact, and its ideological use.

Big Society? Big Corporate.

And here is another issue. Many of the core problems with the Big Society approach realte to its focus on commercial and corporate interests, covered by a fig leaf of community and charity activity. In some ways, these were unavoidably embodied by NCS almost as much as they were by the Work Programme. The Work Programme also hoovered the resources and energy out of the VCS and wider public sector. (Even worse, it closed charities and even public and private providers alike). The Work Programme was claimed by its proponents and progenitors to be successful, but at least one study found it actually got fewer people into work than would have been expected without it.

There was much to be learned from the Work Programme, and the pretty much broadly conteporaneous NCS commissioning and tendering smorgasbord in the early noughties.

And to the credit of NCS, they recognised that this process had taken money out of wider youth services, and when retendering in 2019, wanted to fix the problem. The goal was giving more local organisations a chance to participate, and taking it away from the single provider, The Challenge. But this did not go well.

I worked at the time on building a ‘supply chain’ of small youth organisations for a membership organisation in a second tier organisation. Truly, their goal was to finally make this work for the youth sector. But they found quickly that in a ludicrously commercial contracting approach designed to screw any provider foolish enough to take part, there was no way those organisations could do that. And indeed, no way that even that mediu sized charity could. Just as many providers found in the Work Programme, the small volumes being given to smaller providers made it non-viable. And cherry picking clients would have been the only way to de-risk punitive contracts. Furthermore, the level of financial resilience and legal obligation—at major public sector and corporate levels—was just not on the cards for most youth organisations. When the contracts were initially awarded, most organisations refused to sign. The finances would have bankrupted them, and most of all, the small youth and community providers they were trying to include.

The way the process ran, and the contracts were structured, it was made for Serpita or Capico or even prisons giants Grope 4, and the sheer poverty of the pricing meant that only such an outfit could do it. The negotiations were particularly nasty, and some were quite taken aback by how NCS’s ‘commissioners’ acted. After the initial recommissioning failed, The Challenge went under without its key contract, and the contracts went to… Ingeus and Reed. And a direct NCS trust (similar, I think, to The Challenge, so what was the point of that?). Larger youth organisations, many of them wealthy sporting trusts (who could use funds to subsidise), and a few local councils, took on the delivery. As with the Work Programme, squeezing people until the pips squeaked meant that there was not a viable delivery model for anybody but the biggest players. Many larger medium-sized youth charities spent hundreds of thousands of pounds of charity money on tendering for contracts that nobody could deliver.

What this showed, again, was that the programme had never had that model of real community involvement in the grassroots bedded in at the start—it was made for volume, for one-size-fits-all, and for a commercial, sausage machine approach. NNo doubt part of this aim was to make it more efficient and affordable to the public purse - but it wasn’t. The cost per head for a short programme was up to around £1,800 at various points.

And that was the general takeaway from the Big Society. It had no real connection to community or society - just economy. It used ‘volunteer-washing’ as a way to push responsibility for society largely onto people who were excluded from it, it was never cost-effective, and it was only deliverable by big business (at least, if the public sector was to be abolished). And whether it was effective or not depended on who you asked, much as it was always undergirded at every point by endless metrics and data - that were buried at the first sign of trouble.

Most of all, Big Society took away the real world of society and community and replaced it with corporate fascimilies which were just not very effective. Big Society Boondoggles were like picnic blankets. You put them down on this lovely grass in a meadow, and when you take up the picnic blanket, all the lovely things that were growing there before are dead. Then you take your picnic blanket and go somewhere else.

New Youth Strategy

Even the existence of a new youth strategy is good news in so many ways - to have one feels momentous.

I share the concerns of others that this may include more splashy programmes and boondoggles. But what I have seen of it so far seems to at least be making gestures in the right direction. Things like enhancing youth participation are absolutely key - although I hope this is done carefully and properly. (Get Josh Harshant to do it.) The funding commitments, if they are real, are encouraging, with over £85 million from the government and £100 million from the Dormant Assets Scheme to overhaul youth services and facilities. (It sounds like a lot but compare it to £1.5bn.) And a localised approach, moving away from a uniform strategy to one that really focuses on young people and their communities. The devil will be in the detail.

Clearly, re-establishing on the ground youth provision in key areas has to be part of it. At the same time, real, serious thought needs to be put into what a youth work model that works is in 2024. It may be similar to what has been around for many years, but it may not. When they last really existed, youth work models were about 50% Poor School and 50% Rainbow Corner/ Red Cross Clubs. That may indeed be what we need, but I’m suspicious of people who claim it should just be the same old youth club but with a TikTok account. Then again, I’m equally suspicious of the ‘innovators’ who will undoubtedly pop out of the woodwork and tell us that their patented new solution will save us all. That, after all, is what Kidscompany did after the riots.

And we need to bear in mind how much the world has changed - young people who barely met another human being for 2 years. Postcode wars and county lines. Parents who don’t want their children to go near other children in case they are putting them at risk.

And yet many other things are the same, I suspect. I do think young people like having space to do their own thing, spend time with friends and make new ones in a non school environment. And I do think they want chances to try new things. And I think they want support from trusted adults who understand them, and the chance to build secure attachments in a difficult world. And to feel like their needs are heard and then met, especially when they may be different from those of their peers.

That sits alongside so many other specific needs that young people have, especially in an age of worsening mental health, and rising poverty and inequality. But I feel, for the first time in 14 years, a tiny wee bit of hope.1

Oh, and finally: look up the word boondoggle and where it comes from. Very interesting in relation to what we’re talking about here.

General sh*tshow updates

Not much in terms of shit show updates this week, but here is a bit.

First, it’s remarkable to see just how closed everything is looking on the grantmaker side. For example, London Community Foundation doesn’t have a single open programme at present. That seems unusual. What do you think? (Edit: they’ve got in touch to say they only just closed a programme on October 16th, and people should check back throughout the year.)

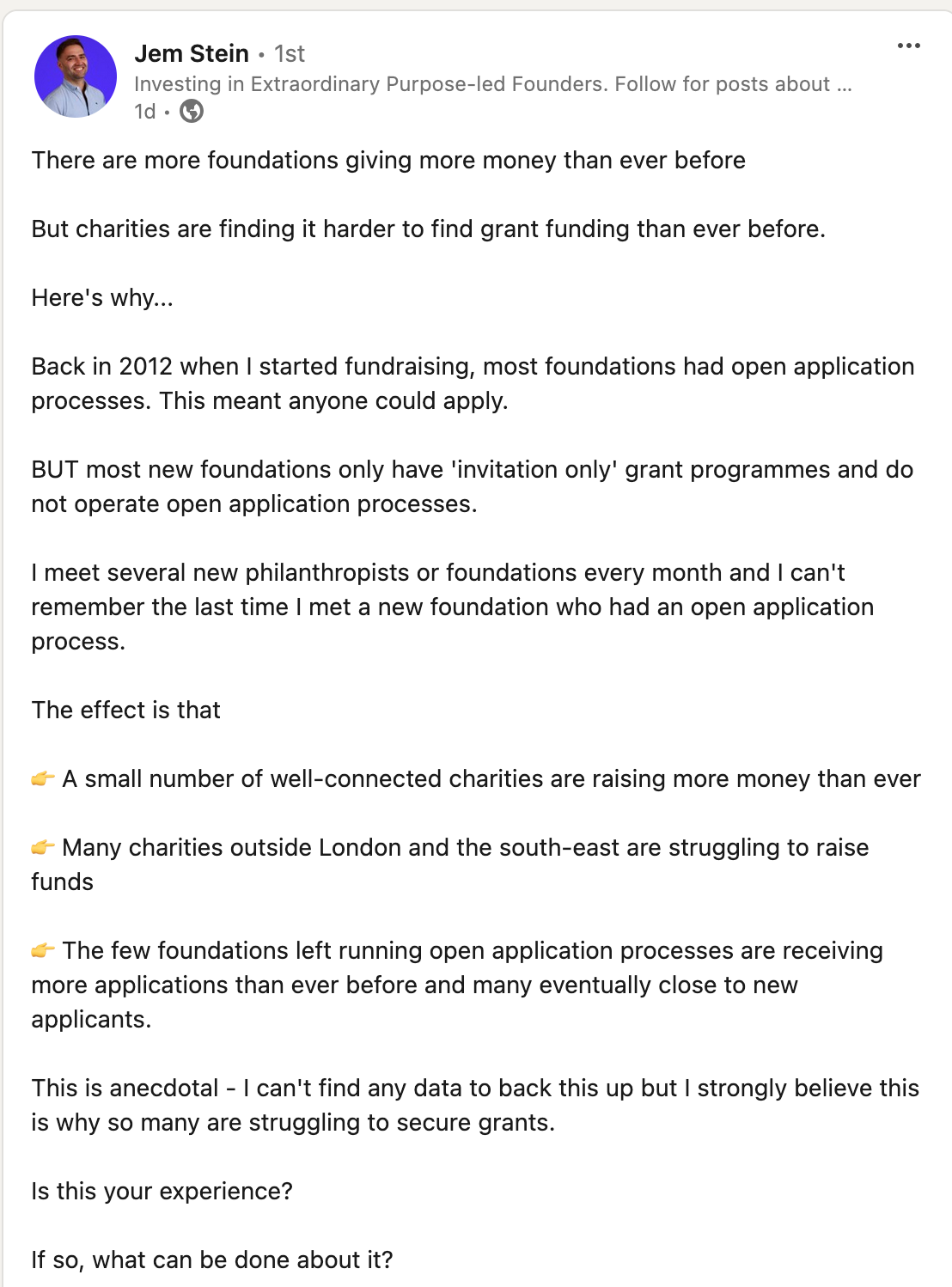

Second, Jem Stein, one of the more interesting Linkedin people, had this to say about changes in trusts and foundations. I’m really interested to see if this is the case. 2

This strikes me as very likely. I think it’s part of the general shift back towards Victorian/ Gilded Age 'philanthropists' who see themselves and their connections as the arbiters of what humanity needs, and who should get their money. This is not so much the established foundations, but the newcomers still very much connected directly to their founder.

This approach is being encouraged by things like the extremely scummy Effective Altruism and Longtermism movements, and the new cheerleaders of ‘engaged’ philanthropy, as well as the banks and various finance providers and platforms who are now driving people through their own mechanisms - and ideological standards. Worrying.

If this interests you, take a look at this excellent lecture by Professor Hugh Cunningham, who will show you we’ve been here before…. Gresham College is an absolute gem, btw.

Meanwhile, some of you may have been at the A Civil Alliance conference sponsored by Henry Smith charity and run by Pro-Bono Economics on Thursday. I somewhat naughtily noticed that all the in-person tickets for civil society people were gone almost instantly, while there were still some available on the day for the civil service…. You don’t say….

A very useful and encouraging line in the sand, I thought, and the new Civil Society Covenant is well worth doing. I just hope that we can get past saying warm things to each other and start thinking about what practical things there might be we could do together. What struck me most of all, however, was that I literally would not have known how to even start in contacting a civil servant when I was in delivery charities. These people are not waiting for most charities to pick up the phone and give them their take on the issues of the day, and even if they were, their numbers are ex-directory. What can it all look like practically?

Finally, I bet we were all delighted to see the Captain Tom verdict from the charity commission - although I will be trying to explain that not all charities are like that to my right wing relatives for months now. The thing is, at the time they were all cheering it on and saying how wonderful and inspiring it was, while I was sitting there like, “Sigh…. We all know how this is going to end….”

Anyway, stay frosty people (literally given the weather), and let me know if you see anything interesting you’d like me to cover next week.

Oh wait!

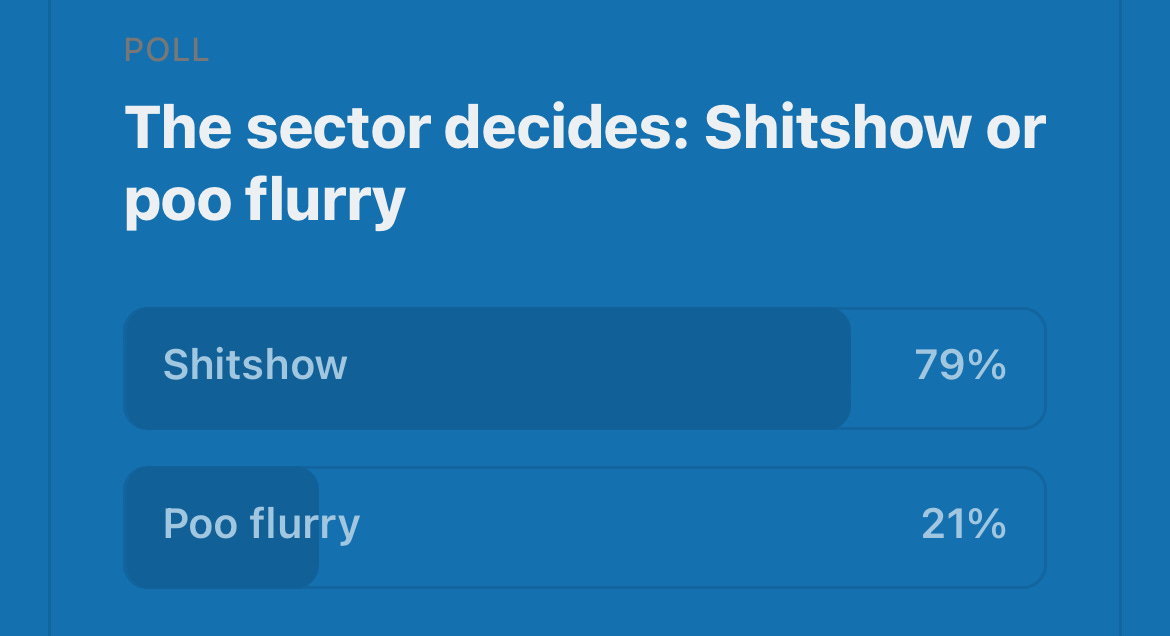

And the winner is….

Shitshow. By a long chalk. Your wish is my command.

Can I help?

You’ve got this far. I’m amazed, I was flagging by this stage.

But can I help? From research and evaluation to facilitation, strategy development, public speaking, for grantmakers, grantseekers and everyone inbetween. Drop me a line. Link to refreshed website below.

I was writing this mostly on a mobile, and that doesn’t allow links, so here are some useful links on the above, where I got my info from.

https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/minister-peacock-speech-at-a-civil-alliance-collaboration-between-civil-society-and-the-civil-service

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2024/nov/21/captain-tom-family-personally-benefited-from-charity-they-founded-report-finds

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-21532191

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-19822669

https://www.civilsociety.co.uk/news/national-citizen-service-trust-s-income-dropped-by-69-in-four-years.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/david-cameron-youth-citizenship-spending-money-funds-ncs-council-big-society-a8472931.html

http://www.thirdsector.co.uk/national-citizen-service-legislation-given-royal-assent/policy-and-politics/article/1431920

http://www.cypnow.co.uk/cyp/news/2002997/national-citizen-service-initiative-costs-too-much-spending-watchdog-warns

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-national-youth-strategy-to-break-down-barriers-to-opportunity-for-young-people

https://www.linkedin.com/in/jem-stein-8751959a?utm_source=share&utm_campaign=share_via&utm_content=profile&utm_medium=ios_app