Charity Shitshow updates, October 2025

A news roundup to warm your cockles or turn your stomach. Class! Data! Corporates! It's a complete binfire.

The brief introduction

Welcome to another week of Barely Civil Society. No big essay this week, just a newsy roundup.

I’ve had to take a break from fascism for the last couple of weeks. No, not because, as my partner suggested, ‘My arm was getting tired’.

Because it’s all too depressing and I needed a week or so news-lite, if not entirely free. Still squeaking in, there has been some stuff from the Labour party conference, which seems to have made everything a thousand times worse, so, nice one Keir. I did rather like the Guardian’s description of him having the ‘reverse Midas-touch’.

I guess we’ll see if we get Andy Burnham, and then at least someone easier on the eye can ferk it all up.

Onto the news…

Most corporates officially do not give a fahrk

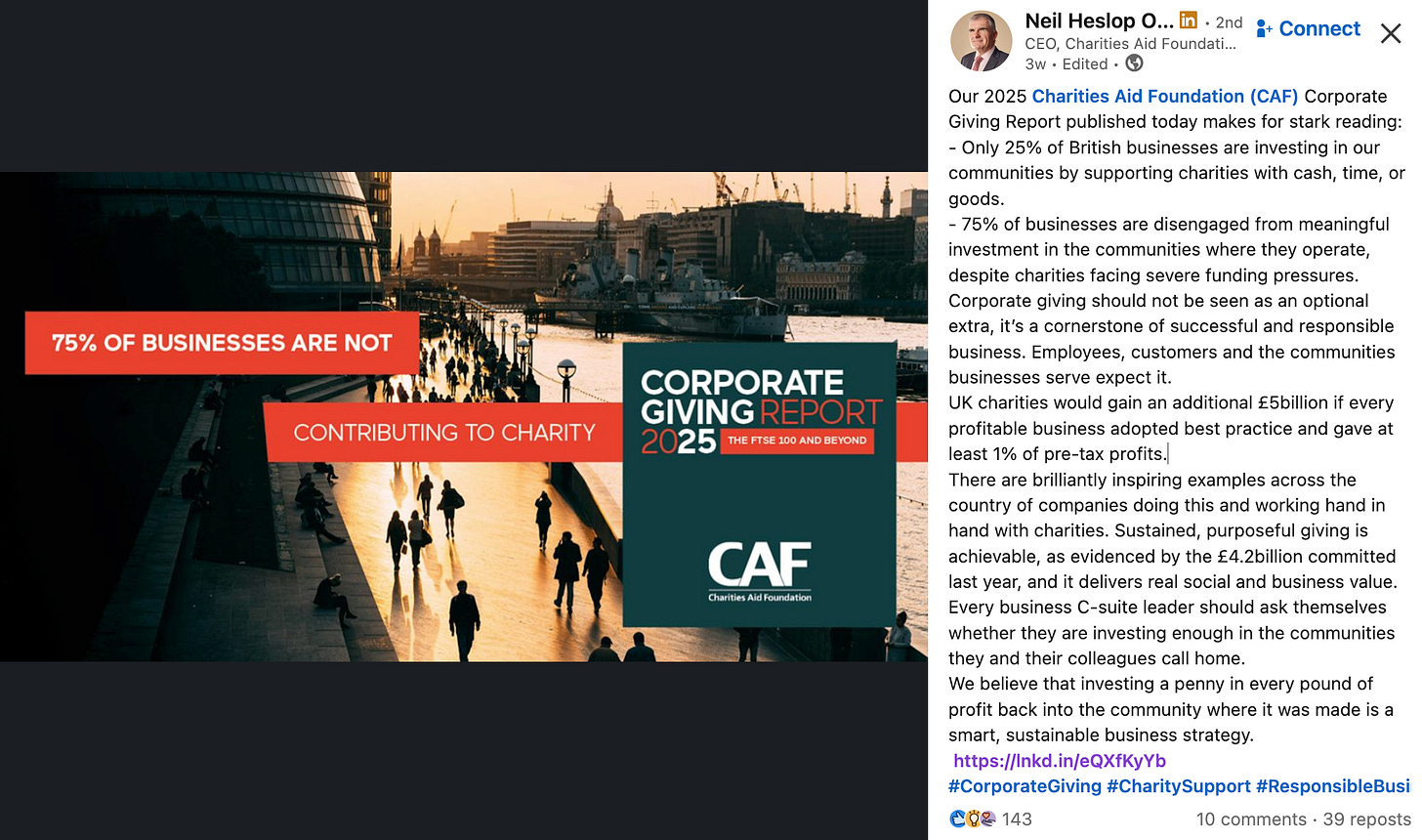

The latest report from the Charities Aid Foundation on corporate giving shows that only 25% of British businesses support charities with cash, time or goods. You will be aware of my rather dim view on the role of corporate giving - and indeed, that it is one of my hard(ish) red lines in terms of things I won’t get involved in, not least because of the high risk of appalling toxic behaviour being unleashed upon charity staff.

But I suppose my concerns are a bit like the old Jackie Mason (I think…) joke:

Old lady: ‘That restaurant! We went there, and the food? Terrible! It would make a dog sick! And the portions were so small.’

When corporates do give, it is mostly about them, and them alone - and you need to always be aware that they must be somehow profiting from, extracting from, the charity through what they ‘give’. (Obviously, say, an owner run business could be different - that’s actually different than ‘corporate’ after all.) Perhaps in a few cases, this works both ways and you get different things you need - you launder my reputation, I pay for your soap powder. But very often, the sheer effrontery of it is mind-blowing.

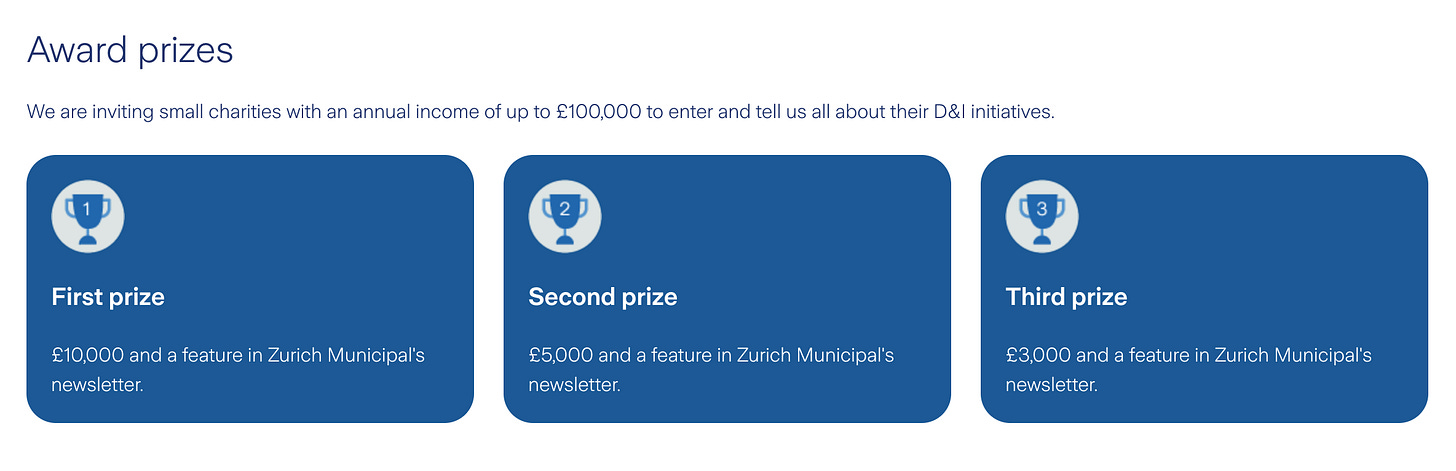

For example, this little doozy - a corporate ‘award’ - always the very shittiest of all deals for charities - run by a major insurance corporation.

First of all, quite why the corporation thinks they are best placed to ‘award’ a grassroots charity for its contributions to diversity and inclusion is pretty mind-boggling. Talk about hubris.

But then look at the ‘prize’. £10k first prize. Second £5k. Third £3k. Hmm, couldn’t spring for a fourth? No wait - that’s admin costs!

It’s like: ‘Tell me you had £20k for CSR in your marketing budget, without telling me you had £20k for CSR in your marketing budget….’

Meanwhile, not to belabour the point, I’ll just leave this here:

As for CAF recommending everyone donate 1% of their profits. I’ve got another idea, and it rhymes with ‘make them pay more tax’. Sorry, wait, it is ‘make them pay more tax’.

More on class: I appear on a podcast and everybody runs away screaming

CLASS. Yes, it’s a thing. You may have heard me mention this once or twice.

I’m on this this month’s Benefact Group podcast talking to Felicia Willow along with, Dorothea Jones FRSA FIEDP and Duncan Exley, about the ongoing problems with class in the voluntary sector.

As you may know, my focus is historical, and about economic/ material factors that have shaped the sector over at least a millennium: changing ruling class structures that hoard power and tell us who is worthy of ‘charity’ in our society. We started with a church control by priests, moved on to royal control, then to the mercantile classes, then to the bourgeoisie. In every stage of our society, the most powerful/ ruling class has been in charge of charity; either through the purse strings, or through regulatory and administrative regimes.

I care about individuals and their experience of class, but I’m most concerned about how structures and regulations in our sector prevent real and lasting socio-economic change. So yes, underneath it all, I’m, whisper it, a Marxian.1 (Turns out Dorothea is too - respect to you Dorothea!!!) What I’m noticing more and more is that people are treating ‘class’ like a tick box on a DEI sheet - but what they are really describing is something more like ‘the poor’. Class is far more complex than that, because it’s about ruling ideas and relationships to power - and economic/ material means of production. I’m talking about economic class rather than what people sometimes call ‘social class’.

So what are the means of production? Well, think about it like this. If you own a building, machinery, some start up cash, some labour, some land for agriculture, anything like this, you own ‘productive forces’. Having this stuff allows you to ‘produce’ more money and then buy more resources. Then you can generate more profit and buy more resources. And so on. Of course, you do this by getting more money in than you spent out. That’s what profit is, and most of it comes from employing wage labour. So when we look at that, we ask, are you part of the owning class, or part of the working/ earning class? That makes a big difference, right?

Excluding the voices of people from ‘working class backgrounds’ (which I think often is really just a rephrasing of ‘from socioeconomically deprived backgrounds’ as we would once have said) from work or leadership is a massive problem. But there are much bigger, more systemic factors. Class is not a DEI characteristic alone. You see, poverty is a result of class, not class itself. That’s why you can’t usually just work yourself out of poverty if you start from nothing, whatever Centre for Rehabilitating Iain Duncan Smith’s Legacy thinks.

Classes are not just our lifestyles or where we went to school, or how much cash we have. They’re about our economic relationships to material and economic power, again, to productive forces or the means of production. Do you make your money from wealth or work? Do you own your labour or sell it? Do you extract profit from the labour of others? Do you have ‘capital’ - that is money, land, resources - that will make you more money?

The ‘lifestyling’ of class isn’t necessarily helpful. For example, people from poorer backgrounds, very understandably, will object to ‘middle class people’ trying to ‘pretend’ they are working class - like me, some might say. (Lattes are too déclassé for me - mine’s an oat milk cortado.) They’re right that your class expresses itself through lifestyle, and that lifestyle can go on to affect your class (and your children’s). That’s what Pierre Bourdieu called ‘cultural capital’. But we ignore the material forces that shape that at our peril.

So, much as I recognise these other things as vitally important, I think it’s most important of all to remember that ‘classes’ in Marxian and anticapitalist critique are really talking about people in our society who share particular relationships to material and economic forces. Because what happens then is that those ‘classes’ of people in society battle it out to decide who is in charge, and who gets to exploit whom.

For example: what do we tax more? Wealth, or work? Businesses or employees? Different ‘classes’ in our society will have very different ideas about that, because people who have a lot of wealth want us to tax work. People who do a lot of work will want to tax wealth - unless they read the tabloid press in which case they will be begging to have their homes repossessed by the Duke of Westminster because Rupert Murdoch told them to.

Those ‘classes’ will come with all sorts of reasons why they are the ones who should be top dog. We call these kind of ideas and ‘reasons’ ideology. They’re justifications of the way things are, or should be (and we all have them…. You’re listening to mine now).

So you can see there are big structural questions being decided and fought out by ‘classes’ which are much more than just who gets a job interview because of their accent. The point is that when we treat this like an HR problem, or a ‘community consultation’ issue, or even a matter of ‘social mobility’ (helping poor people work harder to be less poor), we miss the need for massive systemic changes to how we organise our society and our economy, and who owns and benefits from our collective assets. Changing education systems, redistributive tax policies, and an intersectional (in its positive sense) approach to social change are vitally important. But even beyond economic redistribution and the engineering of more equitable opportunities for mobility, there is also a question of how much we are letting capitalism, and its extraction of profit, and its theft of resources by the few from the many, shape our society. Ownership is just as vital as redistribution and social inclusion.

Back to charities, who have so often been given the role historically of preserving class relations: we are the apolitical safety valve for the poor masses to avoid deeper change. That’s why whichever class is in charge at any point has ended up being in charge of charities. But I think that can change. It starts with us making more noise. It starts by us being willing to challenge the dominant narratives. And by refusing to simply act as the window dressing on capitalist profit extraction when we know better than anyone how unsatisfactory our work is for economic change.

One of the bits I recorded that didn’t quite make the cut was that there are a lot of different things that charities can do to make themselves a pain in the arse for capitalism. For example, the law centres I’ve worked with who are holding property developers to account for their attempts to ride roughshod over social housing regulations, or to displace unprofitable tenants from city centres. There is much more capacity for disruption than we imagine, if we are brave, creative and strategic.

As for our industry itself - central to change is interrogating and starting to shift the trustee machine, and challenging the regulatory, depoliticising role of the Charity Commission. Meanwhile, while rejecting our role as piecemeal redistributors, we can wholeheartedly campaign for deeper change.

Check out the podcast anyway, and try not to notice that my voice sounds like it’s coming through a cardboard tube, not for technical reasons, but because I had flu.

Thanks again to Felicia for having me on - she’s such a ray of sunshine.

The above dude is so right, and both his intelligence, and his pecs, are intimidating.

Meanwhile, you can find more discussions on class and the charity sector in BCS here:

Class in the charity sector

What do I mean by class, and why does it matter?

Beyond charity: A glimpse of a socialist future

Beyond charity part two: Beyond socialism?

Beware the Centre for Social (Victorian) Justice

Disappointing meanwhile to see the Charities Aid Foundation sharing the podium with the right-wing neo-liberal Victorian-styled philanthropy organisation set up by Iain Duncan Smith to justify austerity and welfare cuts.

Apparently, the relationship between charities and Government is often poor. Well, tell us something we don’t know. But hey, I guess even a stopped clock is right twice a day. Meanwhile, if you’re interested in who is behind this organisation, start here.

Here come the data pixies….

More data. More impact. More pixie dust. I honestly felt depressed when I saw the announcement about the latest DCMS magical data pixie proposals. No shade on PBE, although I do feel they could prioritise different approaches.

But my point is that we keep returning to data as a panacea - or a sprinkling of magical pixie dust - as if ‘knowledge’ or ‘evidence’ or ‘understanding’ is what our problems in the third sector, or even more broadly in social care, are really about.

What bothers me is the swell of starry eyed tech bro data-hyping, and the third sector people who hang on their every word, after this and every other announcement about ‘data’ ‘sharing’. (This is a part of a wider societal obsession I’ll discuss in a future essay - but suffice to say, it’s not just AI that is a bubble. It’s data hoarding itself.)

On this particular development, I have so many questions.

Why did we close the What Works centres if this is what was needed? (It wasn’t, and it isn’t.) What happened to the data and evidence that learned ‘what worked’? Did it ‘work’?

What or who is this intended to influence? The State to provide more money to commission the voluntary sector? Really? We already know things are effective, there are endless stacks of ‘evidence’ and ‘data’ and the VCS is already provides vast amounts of public services at low cost. What has happened to all the other ‘evidence’ and ‘data’ we have been hoarding for years? What new information do we want to know? What do we not believe there is ‘evidence’ for already? Being nice to people is better for society? Surely not.

I find it disappointing that we are still putting our efforts into ‘proving’ the value of the VCS when we could be challenging the threadbare, evidence-free economics of the latest neoliberal Government and the terrible decisions, against the advice of even the IMF, that affect the people charities work with, and indeed our whole society. Too few think tanks and economists are doing this. PBE are wasting thier considerable expertise and platform.

If we really believe that arguments on the basis of cost and ‘value’ rather than ‘values’ will tell us the best use of resources, can someone tell me the financial value and return of this exercise?

People who believe the VCS still has to ‘prove’ its value by a financial metric, or by other forms of the holy grail/ fairy dust of data (BEHOLD! ABSOLUTE REALITY!) are not people who want to support it. Seriously, Just say ‘no’.

You can collect all the data in the world into ‘one big database’ as some dude fantasised on LinkedIn, and then what? Crappy junk data that nobody agrees on, comparing apples with anacondas, and with more null values than the list of IQs at a Reform party conference.

What would this magical, passively collected, data allow anyone to do? What structure would we agree on to ensure it has even the very smallest chance of being more useful when centralised than it is when spread across a thousand different sources?

What data, and to whose purposes is this to be applied?

But I think it is all starting to drive me to an overall question that came to me this week:

Has anyone noticed charitable delivery getting better since we started obsessing about ‘impact’ and data all the time about 20 years ago? If it did, would we know? And if it hasn’t, what makes us think it will if we just keep collecting and sharing more of it?

Anyway, £2.5m, and £600k per annum isn’t much in the scheme of things. The annual cost is about half a local CVS - so why not?

But I do worry about any time anyone pretends that ‘data’ is what is needed to demonstrate ‘value’ and ‘unlock’ public, or indeed, private funding. Once more for those at the back: the paymasters don’t need data. They. Just. Don’t. Want. To. Pay. Demands for data are very often simply another way of saying ‘go away’. It’s the equivalent of miming throwing the ball for a not very smart dog but keeping it in your hand. It keeps the dog occupied while you eat your ice cream.

Meanwhile, a few books about the critique of what is called ‘data’ (usually just meaning the metrics of neoliberal statecraft) for those who think this is the critique of one crazy person in the voluntary sector.

The Cult of Efficiency - Janice Gross Stein

The Metric Society - On the Quantification of the Social - Steffen Mau

Capitalist Realism: Is there no alternative? - Mark Fisher

The Tyranny of Metrics - Jerry Z. Mueller

Some Social Implications of Modern Technology - Herbert Marcuse

Charity closures hit the press

It’s encouraging - in a way - to see the national press in England and Scotland covering closures and contractions of charities. With that said, I’m sure the numbers quoted are the tip of the iceberg. The level of redundancies seems to me to be even more striking. It also fails to look at who and what is closing. Jo Jeffery has a briefing note on this coming out soon.

The List goes Live

Meanwhile, Jo’s Magnum Opus, ‘The List’, of ongoing UK charity funder changes and now has its own live website, and it looks beautiful.

That’s it for this week. See you again in a couple of weeks or so for - if there is time - a another essay.

Have a good first half of October.

Alex

Weekly internet nonsense

Barely Civil Society is about making the nonprofit world braver.

Here are three ways to help.

Subscribe!

Barely Civil Society is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Share!

Support!

Buy me a coffee and keep me anxious and crabby. Or help me fix my toilet, which I am having to get replaced next week.

Send me a message

The messages people send me every couple of weeks are my favourite thing. Drop me a line and say hi! What made sense to you? And what didn’t? (Be nice.)

Work with me!

Check out my day job webpage.

Or don’t. See if I care.

Why ‘Marxian’ and not Marxist? Well, these days some of us tend to hedge our bets when it comes to describing our work or ourselves as ‘Marxist’ partly because relativelty few people these days view themselves as full adherents to doctrinarian ‘Marxism’ as some might peeceive it as a whole body of work or political movement. In muy particular case, I find Marx(ian) thought extremely helpful for analysis, but I’ve never been a fan, to say the least, of the Communist Manifesto, which I think is a blueprint for just the kind of terror and cruelty that we saw in the Soviet Union and other places. Many Marxists claimed, especially after DeStalinization, that had just been an aberration or an incorrect application. I disagree - I think it was just a terrible idea. (Those who still adhere to these full on revolutionary, violent communist approaches have long been referred to by other modern day socialists as ‘Tankies’, especially after the horrors of the 56/ 68 Soviet-Czech invasions.) As I’ve said before, I’m much more of a lily-livered Kropotkinite, a bit of an anarchist (probably because gay and ADHD) and more of a socialist democrat. None of which I see as unproblematic either. Guess what, politics are complex. Who knew?

Thank you for this, I found it really informative and I feel like my eyes literally opened wider at 'has delivery improved at all since we all became obsessed with impact data?' I was interested to read your observation that 'working class' has now come to be interchanged with ' from socioeconomically deprived backgrounds' and how actually the definition is more connected to the systems and structures of who is buying/selling labour. So much for me to go away and read and think about! Thank you.

Great article (as ever). I'm seeing a big rise in interest in 'social value' again from the small charities I work with. I had hoped that we had cycled back to focusing on learning & talking to clients to understand their experience, rather than 'proving' worth...